Politics & Society

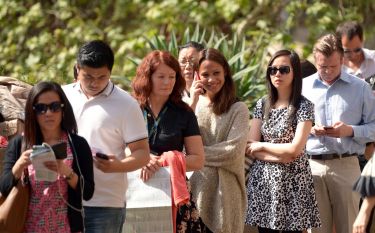

Using design to put voters at the heart of elections

The real secret to how and why Australia adopted compulsory voting was simplicity as well as a hint of classism

Published 15 April 2016

Elections in the US may prove America has a greater share of idiots than Australia.

This isn’t a comment on the voting intentions of the American public but rather the ancient Greek sense of the word derived from the noun ἰδιώτης: someone preoccupied by their private affairs rather than affairs of state and, therefore, unlikely to show much interest in voting.

In Australia, we have to vote – it's compulsory – while in the US people are free to be idiots if they like. Sure, when faced with an unedifying set of candidates you don’t have to be an idiot to decide not to vote.

Recently, in 2020, voter turnout in America's presidential election soared to levels not seen in decades. But if we look back to just over a decade ago, in the 2012 presidential election, barely half of eligible voters in the US voted.

If we turn to Australia, the 2022 election turnout fell below 90 per cent for the first time since compulsory voting was introduced for the 1925 federal election.

Under Australia's federal electoral law, it is compulsory for all eligible Australian citizens to enrol and vote in federal elections, by-elections and referendums.

Politics & Society

Using design to put voters at the heart of elections

Back in 2016, the then-US President Barack Obama praised compulsory voting, saying if introduced to the US it would help “counteract” the influence of money on elections.

Australia is one of 26 countries where voting is compulsory – but only 12 (including Australia) actually enforce it by law.

Many South American countries have made voting compulsory, but interestingly Australia is the only English-speaking country to do so.

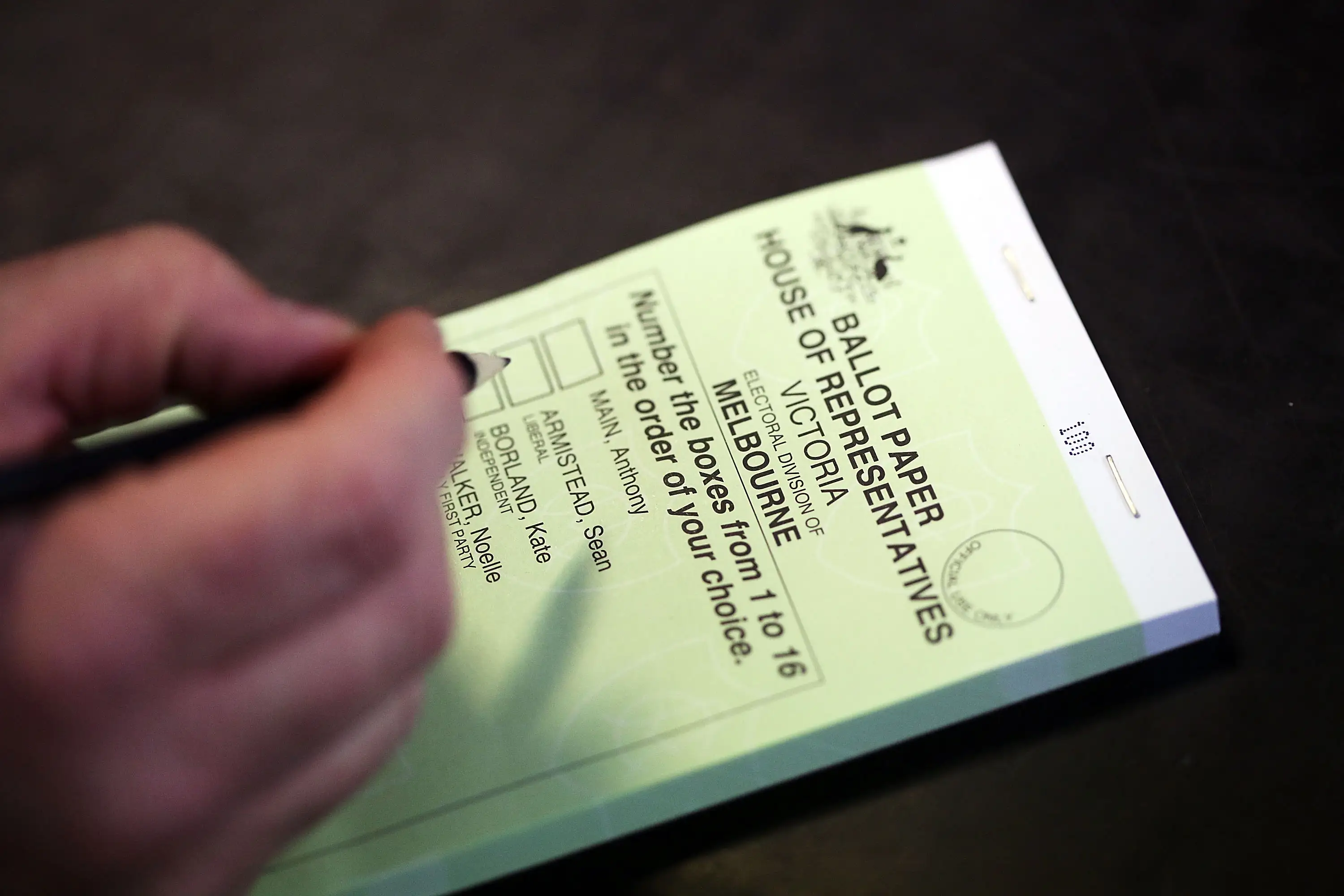

Of course, Australians don’t have to actually vote for anyone.

Around five per cent of ballots for the House of Representatives were filled out wrongly or not at all in the 2022 election – but we do have to physically turn up to vote as our civic duty, and the vast majority of us do.

But there are criticisms.

Compulsory voting in a system like Australia’s that has preferential voting increases 'donkey' voting – this where voters simply number preferences in the order they appear on the ballot paper because they don't want to vote for anyone.

But these votes count as legitimate.

The rarely told story of how Australia came to require its citizens to vote starts with a pragmatic, if not cynical, attempt in 1911 by one party to gain a political advantage.

But in 1924, it is unanimously endorsed as a matter of principle by both sides of politics after a massive slump in turnout in the 1922 election.

This saw figures drop from more than 70 per cent (which had been the norm) to just 58 per cent.

Politics & Society

The reckoning of Gillard’s misogyny speech

“Both sides of politics were really concerned about the political apathy seen in 1922 and both parties could see the virtue of having a full electoral roll,” says University of Melbourne PhD history student Katherine Allan, whose undergraduate thesis explores the processes that delivered compulsory voting in Australia.

The idea of compulsory voting had been talked about soon after Federation in 1901, but was only debated when the ruling Labor Party moved to ban postal voting.

Labor was concerned that upper class types voting for the rival Liberal Party were using the postal vote to force their servants to vote the same way they did.

According to University of Melbourne Emeritus Laureate Professor of History Stuart Macinytre, “Labor claimed there were more postal votes from upper class Toorak than in the whole of Western Australia.”

But the legislation, which passed, also included a proposal to make registering to vote compulsory.

The idea was to make the maintenance of the electoral roll more efficient. But for the opposition it begged the question – why not go the whole way and make actual voting compulsory?

Former Liberal prime minister Alfred Deakin called the measure “ridiculously incomplete”. But while the point was acknowledged it wasn’t pushed.

Then, in 1914, the idea got new life when the Queensland Liberal government adopted compulsory voting in a bid to stave off a looming electoral defeat, only for Labor to romp home.

The next year Labor adopted the principle of compulsory voting.

Politics & Society

Regenerating political leadership in a populist age

But World War I and a devastating split within the Labor Party meant the issue remained off the agenda.

Labor prime minster Billy Hughes and some fellow rebels split from the party over Labor’s opposition to wartime conscription, and instead merged with the Liberals to keep government as the Nationalists.

The merged party would retain government until 1929.

But Katherine Allan says that after the war the issue took centre stage when voter turnout in the 1922 election plummeted.

“What you see in the 1924 debate on compulsory voting is everyone referencing the worrying fall in participation."

The final debate was noteworthy for the lack of any real opposition.

It passed unanimously.

As Professor Macintyre says, regardless of the principles around compulsory voting, both sides could appreciate the benefit of not having to do the painful door knocking needed to simply get people out to the booths.

But high principle was invoked.

The legislation was proposed as a Private Member’s Bill by Nationalist MP Herbert Payne, who argued that it would bring “a wonderful improvement in the political knowledge of the people” and make them “take a keener interest in the welfare of their country”.

Politics & Society

Australia’s referendum drought

Australia’s adoption of compulsory voting was partly rooted in the country’s peaceful transition to independence from Britain and the pragmatic philosophy prevailing at the time, says Katherine Allen.

This “utilitarian” thought acknowledged the power of the state to coerce citizens for the greater good.

By contrast, US independence was only gained through a war over more inflexible “inalienable” rights.

“Having a low voter turnout wasn’t a problem unique to Australia, but what was different was Australia having a parliament that discussed the question of whether the state had the right to make people vote.

"Then deciding that the virtue of having full representation of the people was something that outweighed the coercive nature of compulsory voting,” says Katherine Allan.

Perhaps the real secret of why Australia adopted compulsory voting was simply that it was never seen as a contentious issue.

Decades of public opinion polls and Australian Election Study survey results show that support from the public has consistently hovered around 70 per cent.

Something Katherine Allan says is unlikely to change.

“There is a sense through all this that it simply wasn’t a big deal. It is so accepted here now and I think that acceptance has been there all through the history of compulsory voting,”