Business & Economics

Cosmetic surgery and the workplace beauty premium

New research finds economic inequality can actually incentivise some women to use their attractiveness to try to get ahead

Published 26 November 2019

We may like to pretend, in Western society, that beauty doesn’t matter anymore and that we have transcended superficiality. But sadly, both research and many of our day-to-day experiences say otherwise.

Attractive people are usually stereotyped as more socially competent, having better earning potential and a higher professional status.

These effects are especially true for women.

In fact, attractiveness causes what’s called a Halo Effect, meaning that a good impression in one area, like looks, can lead to a good impression in others, like competency or kindness.

This can be particularly profitable, with a cash value attached, on social media.

Business & Economics

Cosmetic surgery and the workplace beauty premium

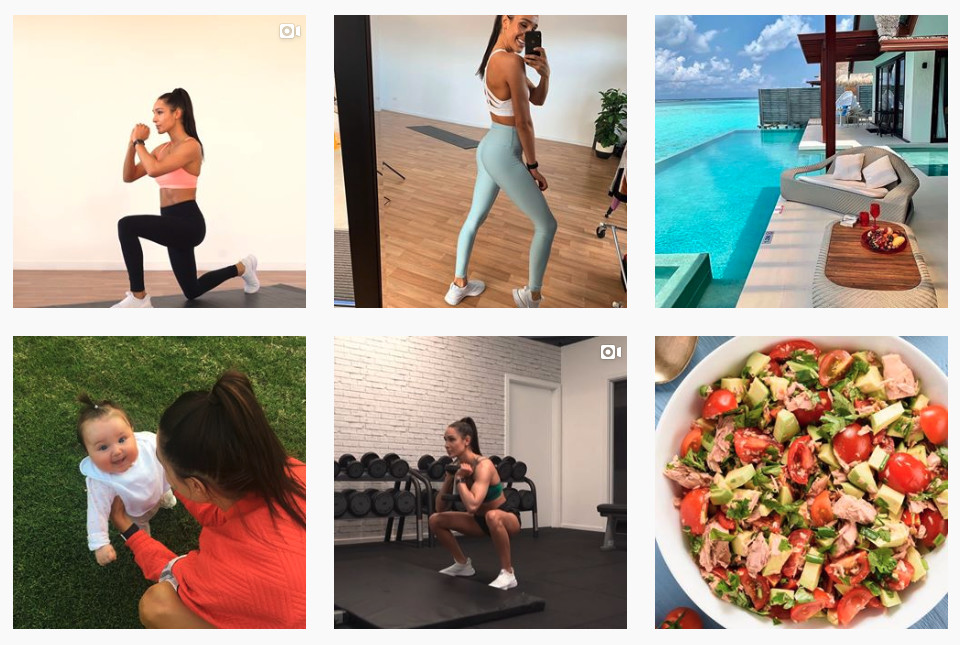

Look at Kayla Itsines, a famous fitness coach and Instagram Influencer from Adelaide. At 12 million followers worldwide, someone like her could be earning an average of $A30K for every Instagram post.

And let’s not even get started on Kim Kardashian, whose followers and earnings are more than 10 times greater.

So, it’s easy to understand why many people, particularly women, end up associating beauty with higher economic and social status. And some end up trying to emulate what they see on social media to get ahead in their own lives.

Our new research explores how the pressure of economic inequality – that is, the unequal distribution of income and opportunity between different groups in society – can impact on the way women try to raise their social standing.

And we found that this inequality in society can actually incentivise some women to use their attractiveness to try to get ahead.

In modern Western societies, most men and women can compete in the social world on a much more even playing field than it was in the past.

With movements like #MeToo, #BalanceforBetter and #HeforShe pushing us closer towards gender equity, men and women in countries like Australia are much more likely to experience equality in some, but not all, spheres of society.

Health & Medicine

Sexual objectification harms women

When psychologists talk about status, it means the relative rank that an individual holds, compared to others, in society. It can be judged on the basis of a number of factors including financial success, popularity, prestige, and attractiveness.

But status is one of the most important incentives for motivating social behaviour, and some psychologists argue that it is a fundamental human motive.

International research has found that high-status people receive more positive social attention, enhanced rights and perquisites, more influence over decision-making and better access to resources.

And a person may seek to raise their status to get access to these kinds of opportunities and benefits.

But for many, economic inequality stokes status anxiety, making us concerned about where we sit relative to others. In fact, this inequality affects everyone the same way in the social hierarchy, with the rich and poor alike becoming more preoccupied with their social standing.

This heightened environment can give us a better insight and understanding of women’s traits and behaviours when it comes to getting ahead in modern society.

Business & Economics

Workplace bullying in the #MeToo era

In previous work, we investigated the role income inequality played in elevating incentives for female attractiveness.

We tracked tens of thousands of social media posts across 113 countries, and found that women posted more ‘sexy’ selfies online in places where economic inequality is rising.

In our new study, in order to examine how economic pressures impact on women’s approaches to competing for status, we looked at their willingness to wear revealing clothing in economically unequal environments.

Using a role-playing experiment, participants from 38 countries became a part of a hypothetical society we called Bimboola.

Participants each joined their own version of Bimboola, whose economy was matched to the one of many economies in the world today.

The version of Bimboola with the greatest economic inequality reflected South Africa, where the rich earn around 30 times more than the poor. The version of Bimboola with the lowest inequality reflected Ukraine, where the rich earn around three times more than the poor.

The women in the study were asked to indicate their anxiety about their social status, and then asked to choose something to wear on their first night out in Bimboola.

The clothing on offer ranged from least to most revealing.

Business & Economics

Teaching the next generation of #MeToo

But we also tracked the women’s levels of hostility toward other women in the society, focusing on whether inequality affected their anxiety about other women.

And we found that women experiencing marked economic inequality chose more revealing outfits as a result of their anxiety about their social status.

This experiment highlights how economically unequal societies actually incentivise women to use their attractiveness as a tool to try to get ahead.

From this perspective, it’s easier to understand how, for some women, wearing more revealing clothing could become a strategy to help maximise their lot in life.

Our results favour a view of women as strategic agents, using the tools available to them to climb the social hierarchy in specific socio-economic environments.

It’s important to remember that people try to get ahead in life using many varying strategies. Sometimes these strategies concern material possessions, sometimes wealth and sometimes they concern beauty.

So, should we stop campaigning for gender equity, and simply tell women they should fix their hair and put on more lipstick? Hardly.

Women still only get 85 cents for every $A1 of men’s pay for the same work in Australia, and parity is occurring far too slowly.

But, next time you see a woman preening over her appearance or trying to capture the perfect selfie, perhaps try to judge her a little less harshly.

Being the fairest of them all can be a profitable strategy to trying to climb the tough social and economic ladders, especially for women in modern Western societies that still place too much value on looks.

Banner: Getty Images