Politics & Society

Can Prime Minister Khan really deliver a ‘new’ Pakistan?

To understand why anti-corruption campaigns fail in Pakistan, we must understand the role of kinship and the impact of periods of military rule

Published 29 July 2021

Corruption is a universal phenomenon that’s present in all countries in varying forms and degrees. It’s also ancient.

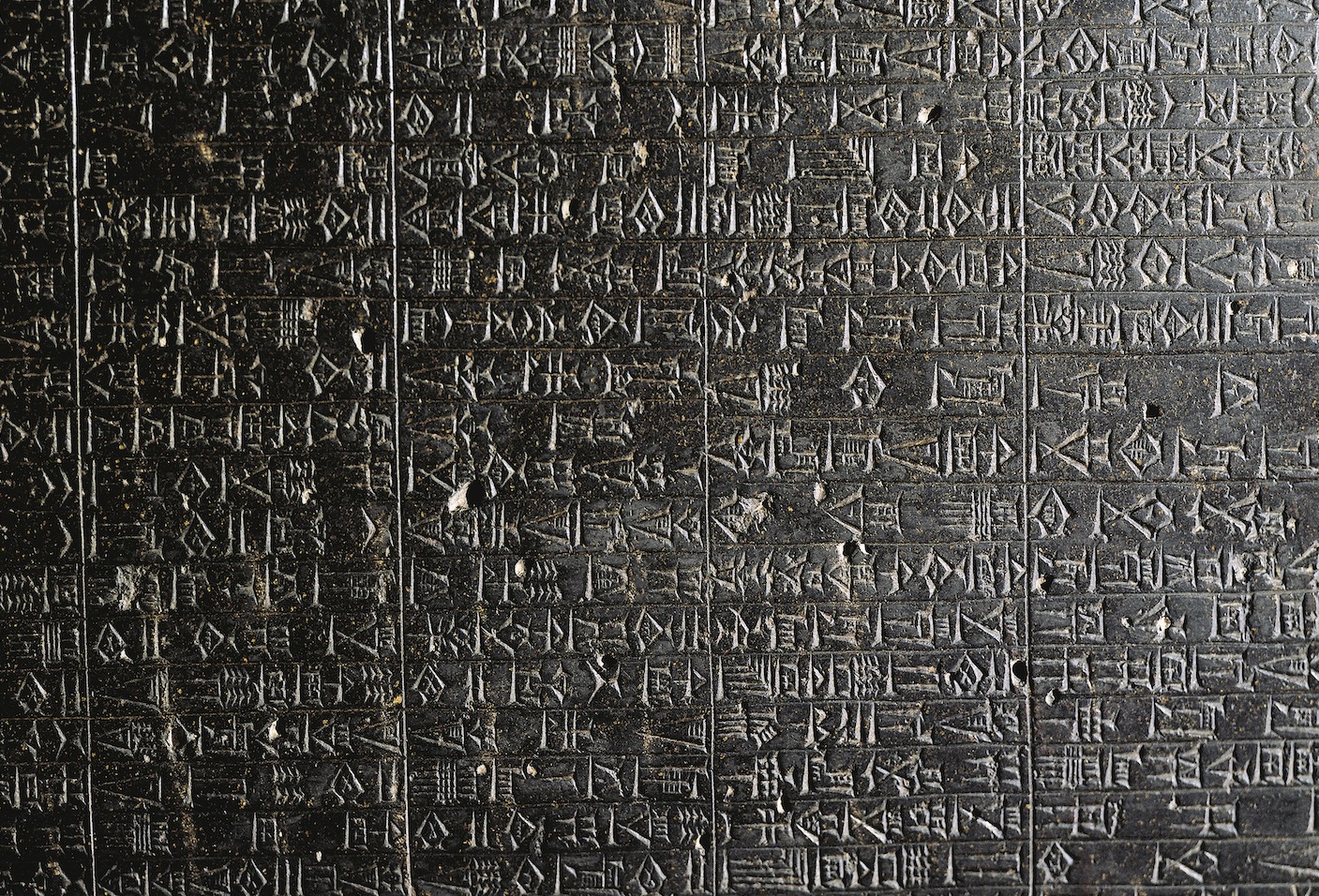

There are references to bribery in many of our historic sources – the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi from the 22nd Century BC, Egypt’s 14th Century BC Edict of Horemheb and Kautilya’s Arthashastra from 14th Century BC India.

Corruption in Pakistan is not a new phenomenon.

Its roots date back to the colonial period when the British awarded lands and titles to their loyalists, leading to nepotism and corruption.

Two significant crises played a fundamental role in the genesis of corruption in this part of the world: defence-related purchases during and after World War II and the allotment of evacuee property after the partition of the Indian subcontinent.

Politics & Society

Can Prime Minister Khan really deliver a ‘new’ Pakistan?

The nationalisation policy of the 1970s created new opportunities for corruption and gave birth to a new breed of corrupt government officers, lasting well into the 1980s.

Although public sector corruption was considered an impediment towards development, it gained a growing focus in developing countries as a result of the neoliberal idea of ‘good governance’ introduced by international donors.

This worked on the assumption that governments in developing countries were inefficient, and one of the primary causes of this was the rampant corruption in the public sector.

So, Pakistan’s then-president, General Pervez Musharraf introduced the draconian National Accountability Bureau (NAB) in 1999 in order to follow international donors’ good-governance prescriptions.

Although General Musharraf introduced NAB to ostensibly control corruption, Pakistan’s current Prime Minister, Imran Khan, took it a step further, initiating an ambitious anti-corruption plan (which was the main slogan of his election campaign in 2018).

Both have failed miserably and instead, corruption increased significantly.

Several significant corruption scandals have been reported during the hybrid rule of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party.

Politics & Society

Corruption and Australia’s Parliament

According to Transparency International, instead of overcoming corruption, PTI’s government significantly increased it in the past two and a half years.

So why have Imran Khan’s good intentions, when it comes to controlling the widespread corruption in state departments, failed?

This failure is a result of misunderstanding the nature, characteristics, patterns and organisational structure needed to devise anti-corruption strategies.

Since the 1950s, Pakistani politicians have been accused of being corrupt. They are singled out as ‘rotten apples’ ignoring social, political and economic structures and are primarily responsible for “abuse of public authority for personal gains” – a Western concept proposed by the famous German sociologist Max Weber.

But there are at least two preconditions required for the application of this concept of corruption.

Firstly, there has to be a sharp distinction between the state and society, implying that the state departments should be insulated from interest groups or kinship ties.

Secondly, kinship societies are ones where individuals exist in relation to others instead of as individuals, but this concept assumes individuals are free of their kinship ties.

For this reason, in countries like Pakistan which are kinship societies, people seek approval of their family members and, in some cases, even of their extended family members or a whole clan for their most critical decisions.

Politics & Society

Principles aren’t enough when human rights meet business

But when these relationships are translated into politics, individuals go through the same process, voting for kinship relations rather than associating themselves with the large unit of society, that is, the nation-state.

They do not vote for political manifestos but instead vote on what they get individually, as families or as communities, from the political candidates.

The system of non-party elections introduced during long periods of military dictatorships, especially for local governments, has had a long-lasting impact on Pakistani politics.

Political candidates could not mobilise people on party bases and, consequently, relied on their clans and castes to support local government elections.

As a result, local government elections led to politics based on clan and caste loyalties and a significantly segregated population along clan and caste lines. These loyalties ultimately strengthened the politics of patronage.

A new political elite emerged from these local councils and came to power through military patronage as well as the strength of their clan and caste.

After becoming members of national and provincial parliaments, these new politicians introduced politics based on their experience of local governance – that is, they introduced the politics of personalised patronage and then subsidised their clan-based constituencies by using development funds to boost their chances of re-election.

Politics & Society

Brazil elections: Is democracy itself on the ballot?

Western societies have gone through several centuries of transformation, from kinship-based societies into nation-states. Many developing countries have yet to develop a sense of association with a larger nation-state beyond kinship loyalties.

This is truer for countries like Pakistan, where several decades of direct military rule has privileged non-party elections and there remains an ongoing military interference in politics.

In fact, the situation has significantly strengthened the kinship system of politics – at the detriment of establishing the state as a rational-bureaucratic entity accountable to people.

In a society where kinship ties have yet to be transformed, a state anchored by patron-client politics has prohibited a clear separation of the state and society – disempowering people to make the state accountable in overcoming corruption.

The military-controlled patron-client politics has also hindered state formation in the country, which still seems to be incomplete.

But again, language is important when it comes to Pakistan. Strictly speaking, there is no state in Pakistan; there’s only an administration, military and civil officials.

The term ‘state’ itself is an elusive one. It seems inappropriate to use the term regarding the institutions of the country. Although there is a ‘community’ with a monopoly over coercive ability, it has failed to devise institutions that confer legitimacy over the use of this force.

Arts & Culture

Rage against corruption

This is true even though there has always been an ongoing effort to build a state, initially by politicians and then by the military since 1958.

In short, unless state formation is insulated from the parochial interests of state institutions, especially the military bureaucrats and kinship-based electable candidates, controlling corruption won’t work.

Corruption in Pakistan is an effect of the incomplete process of state formation, which has failed to establish a sharp boundary between the state and society.

The only way to ensure a weeding out of corruption is to ensure the non-interference of non-political institutions in politics.

But this must be done alongside a sustained process of establishing and strengthening civilian-based democratic institutions and governance that is ultimately accountable to Pakistan’s people enabling them to move beyond their kinship loyalties.

Banner: Getty Images