Health & Medicine

When women’s rights collide with doctors

Menstrual taboos have serious implications and consequences on women, with restrictions enforced on a woman’s daily life, impacting her health and freedoms

Published 20 January 2020

Here in Australia, we’re not great at talking about menstruation.

When Libra’s #BloodNormal commercial aired on prime-time TV last year showing a woman having her period and menstrual blood in a sanitary pad, outrage ensued.

Over 500 complaints were received by the Advertising Standards Board, claiming the ad was offensive, vulgar and inappropriate for ‘family viewing time’.

Although society has progressed, menstruation is still a taboo topic around the world.

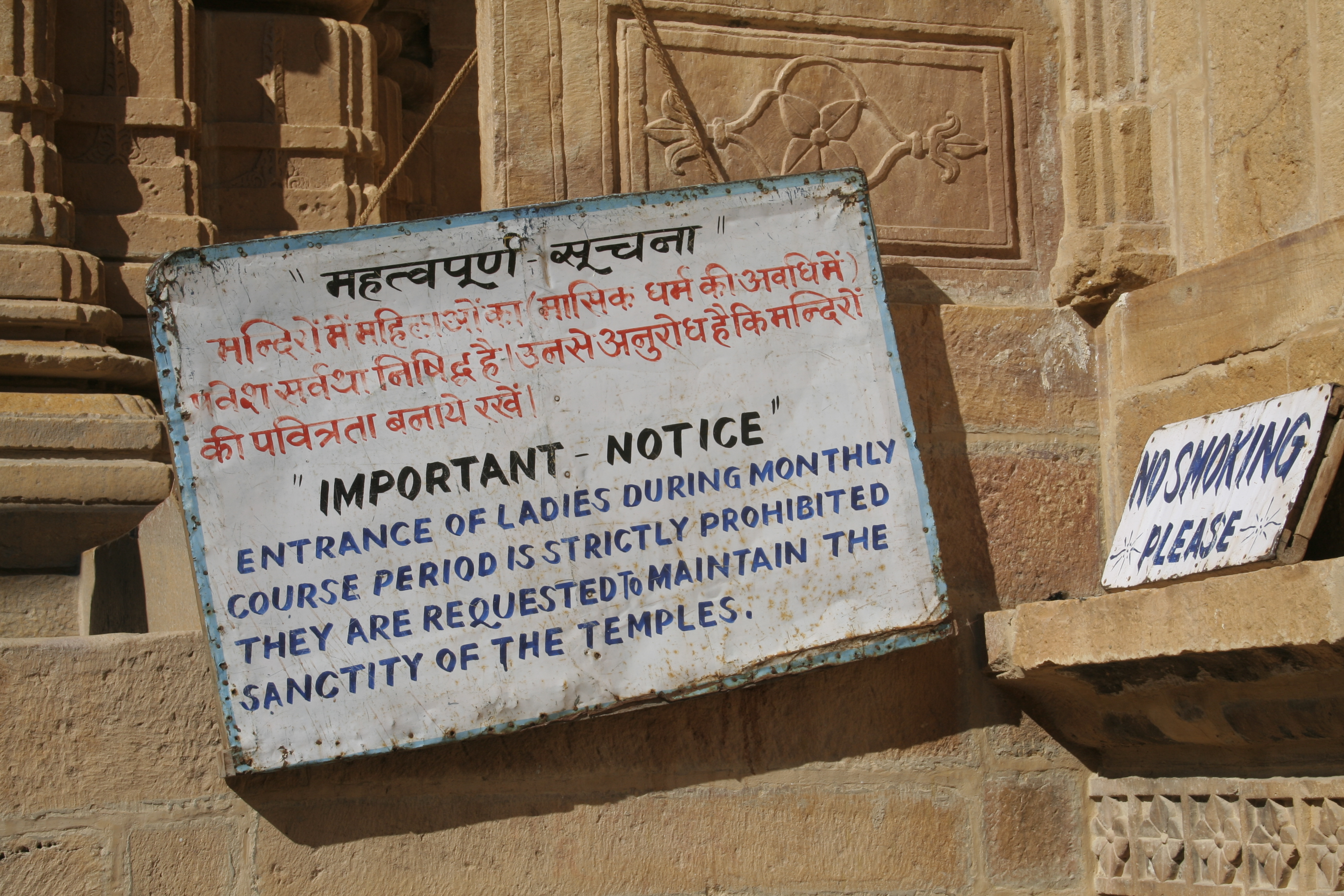

However, in some cultures menstrual taboos have serious implications and consequences on women, with restrictions enforced on a woman’s daily life and activities impacting on her health and freedoms.

Health & Medicine

When women’s rights collide with doctors

Last month, Parbati Buda Rawat, a 21-year-old woman, was found dead in a remote district of far-west Nepal after being removed from the family home to a shed while menstruating in which she suffocated after lighting a fire to keep warm. And she isn’t the first.

Chhaupadi is a long withstanding tradition observed in some parts of Nepal, whereby a menstruating woman is required to stay in a small hut or shed, external to the family home, for the duration of her menses.

Originating from Hindu mythology, the practice is observed as menstrual blood is believed to be impure and harmful to others. Many believe menstruating women are cursed and untouchable, requiring separation from others to prevent misfortune.

As a result, girls and women are prevented from normal duties and tasks, including prayer and visiting temples, bathing in or drinking from a public water sources, eating certain foods, entering the kitchen and touching certain objects and people. Chhaupadi is a particularly extreme form of menstrual restriction.

In many families, the pressure to adhere to the ritual is unavoidable. Characteristics like age, caste and ethnicity and familial composition increase the likelihood a girl or woman will be required to observe chhaupadi.

Issues of social stratification and reputation are significant factors influencing who practices these traditions. For many women, shunning the tradition results in social isolation and rejection.

Health & Medicine

Many of the world’s women are mistreated during childbirth

It is common for girls and women to be exiled to a menstrual hut by older female family members including mothers, aunts and grandmothers.

However, the perception of menstruation as a danger and impurity carries enough weight in some districts that menstruating girls or women may also choose to observe chhaupadi or self-impose their menstrual restrictions, often to avoid stigma, social exclusion and repercussions from her family and community.

Chhaupadi or menstrual exile occurs throughout Nepal. Not every Nepali woman will observe menstrual exile and it is least prevalent in Central and Eastern districts – including the capital of Kathmandu.

However, chhaupadi is observed at significantly higher rates in West and far West districts of the country, particularly in remote and geographically isolated regions. Recent research found 77 per cent of adolescent girls in Achham, far West Nepal, practiced chhaupadi each month. In nearby Doti, another study reported 89 per cent observed menstrual exile.

The way a menstruating woman observes chhaupadi can vary. Most commonly, she is required to stay inside an external hut or shelter, known as a chhaugoth, for the duration of the menstrual period.

The shelter is often located close to the home and may be purpose-built or normally used to house livestock. The confined space, lack of ventilation, heating and security, coupled with the ordinary difficulties of managing menstruation, pain and other symptoms, create an environment of extreme vulnerability.

Health & Medicine

Making every woman count

A 2018 study found shelters often lacked electricity, windows and provision of mattresses or blankets – women slept on a sack, straw or the bare floor instead.

The consequences of a stay in a chhaugoth can be fatal. Women are exposed to the elements and try to keep warm by lighting fires. The lack of adequate ventilation in a small space creates significant danger. Many women have died from smoke inhalation, hypoxia and burns.

There are other hazards too – bites from scorpions and snakes, or hypothermia and pneumonia caused by the frigid temperatures. There have also been multiple reports of sexual assault and rape.

For the women who make it through a stay in chhaupadi, the consequences on their health and wellbeing can be significant. Research shows women who observe chhaupadi are more likely to report health problems during menstruation than those who do not practice exile, including infection, anaemia, caloric insufficiency and being underweight.

Furthermore, the taboo of menstruation and the justification for chhaupadi creates a society where girls and women are discouraged from discussing normal and important questions about menstruation – is my flow normal? How long should my period go for? Should I be in pain?

Menstrual taboos also reduce opportunities for women to properly understand their own menstrual and reproductive health, including menstrual disorders such as endometriosis and polycystic ovarian syndrome. This could have lifelong effects and impact on a woman’s health.

Health & Medicine

Busting the myth that endometriosis is a ‘skinny woman’s’ disease

Menstrual taboos and chhaupadi can also undermine a woman’s mental health and wellbeing.

Studies have found girls and women who observe significant menstrual taboos or exile report feeling ashamed, worthless, lonely and embarrassed. A lack of bodily autonomy, disempowerment and being labelled ‘dirty’ or ‘impure’ increases risk of distress, anxiety and depression.

The news of Parbati’s death is the 15th reported death of a woman while observing chhaupadi in just a decade.

These avoidable tragedies have resulted in local and community-led advocacy and awareness-raising efforts and have drawn global condemnation from organisations including Amnesty International and the United Nations. In 2017, the Government of Nepal outlawed chhaupadi. Anyone found to enforce menstrual exile can be fined or sentenced to a short-term in jail.

Several days after Parbati’s death, her brother-in-law was arrested and is being investigated for his involvement in her death. He is the first arrest since the new law was introduced, and many have questioned whether the laws are strong enough to actually reduce the prevalence of menstrual exile.

In response to increased attention and demands for action, local authorities and advocacy groups in Parbati’s district have begun destroying chhau huts to discourage the practice. The Government of Nepal is even offering rewards and incentives for those who destroy huts.

These actions may mark a significant turning point for Nepal. However, policing, monitoring and documenting the prevalence of chhaupadi is complicated and difficult in a country with sparse resources like Nepal.

Several Nepali organisations and advocacy groups have also raised concern over the effectiveness of tearing down menstrual huts or imposing fines on pro-chhaupadi individuals and groups when the stigmatising beliefs remain unchallenged.

What is needed are interventions designed to encourage and facilitate structural change to eradicate harmful beliefs and perceptions of menstruation.

Until this occurs, it is likely change will be temporary and menstrual taboos and restrictive practices will continue to impact the wellbeing, freedoms and rights of women to experience safe and dignified menstruation.

It’s the middle of winter now in Nepal, one of the most dangerous times of the year for a woman to practice chhaupadi. Many of the deaths in the past 10 years have occurred between December and February. Parbati’s death wasn’t the first as a result of chhaupadi, and she is unlikely to be the last either.

Banner: Women stay in a chhaupadi or menstrual hut in Surkhet District, far West Nepal/ Getty Images