Sciences & Technology

Keeping aged care residents connected

COVID-19 has caused particular psychological stress to older adults from heightened risk of severe illness to social restrictions. We need to know more about anxiety, a ‘silent killer’

Published 30 July 2020

As Victorians grapple with a second round of COVID-19 restrictions, spare a thought for Joan*, an 85-year-old resident of an aged care facility who has not been able to see her family for weeks.

This has made her very anxious and the saturation media coverage of the pandemic only adds fuel to the fire.

It may come as a surprise, then, that although anxiety in older adults has been described as a “silent killer” – it has mostly been overlooked by researchers, especially when compared to the research attention on depression.

Will the pandemic change this?

Our research suggests some catching up needs to happen so that anxiety receives its due attention to make a difference to many people’s lives.

Sciences & Technology

Keeping aged care residents connected

This is not playing semantics: depression and anxiety can co-exist, but that does not make them interchangeable.

Every day, clinicians see many older adults with anxiety like Joan who may be distressed and disabled by their symptoms.

Despite this, our research showed that in the early 1990s, for every nine research publications related to late-life depression, only one was published related to late-life anxiety in people aged 65 years and over.

Nearly 30 years on, that gap has narrowed to 2:1.

But this imbalance still reflects lost opportunities to improve the way we manage a condition that many of us may experience either now or in the future.

There are some key myths out there that may help explain why late-life anxiety has been the ‘Cinderella’ of mental health conditions in later life.

The first is that it’s a young person’s condition.

Epidemiological studies indicate that anxiety disorders, on average, begin at between 11 to 21 years of age.

Health & Medicine

How to take care of yourself if you have COVID-19

However, early onset does not mean early recovery as anxiety disorders are still quite prevalent and persistent in older age-groups, especially in studies that have used tools for diagnosis that are adapted to be more appropriate for the age-group.

A second example of one of these myths is that anxiety is not a ‘severe’ condition.

Historically, it was thought that anxiety disorders were less disabling than depression, but there is increasing evidence that anxiety disorders can have major impacts on function, quality of life, health outcomes, prognosis and health-care costs.

One common type of anxiety condition is called Generalised Anxiety Disorder where individuals experience anxiety much of the time about several aspects of everyday life.

A recent study even found that late-life Generalised Anxiety Disorder affected quality of life as much as depression, and even more than a heart attack or type II diabetes

Finally, there’s the myth that anxiety is joined at the hip with depression.

There’s been a belief that late-life anxiety is typically part of depression, however, multiple studies have shown that late-life anxiety often occurs by itself, and needs to be tackled and researched in its own right.

So, it’s clear that treating anxiety really matters.

Health & Medicine

Protecting our ageing population from COVID-19

Emerging evidence suggests that anxiety may increase our risk of developing dementia.

Two major longitudinal studies that involved neuroimaging – the Australian AIBL study and the American ADNI study – found that higher anxiety is associated with a higher rate of cognitive decline and risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, even after adjusting for depression.

COVID-19 has caused particular psychological stress to older adults both because of heightened risk of severe illness and the restrictions aimed at mitigating this risk, such as social distancing and visitor restrictions for places like nursing homes.

We have already seen the devastating physical effects of COVID-19 in residential aged care facilities around the globe, but there’s also the psychological effects of restrictions – for Joan, a wave through the window is not the same as a visit.

This stress has caused some residents to relapse with their anxiety disorder and require admission to hospital. In the community, people are putting off medical care and there is reduced access to some services as a result of COVID-19.

We have seen older adults with dementia referred to our mental health service by worried families as they are unable to understand or remember the COVID-19 restrictions, and may struggle to remember to wear a mask.

Sciences & Technology

Modelling the spread of COVID-19

Given the twin threats of COVID-19 infection and the stress of quarantine, it’s not surprising that The Lancet Psychiatry Position Paper on Research Priorities for COVID-19 has identified older adults as a “population of interest”.

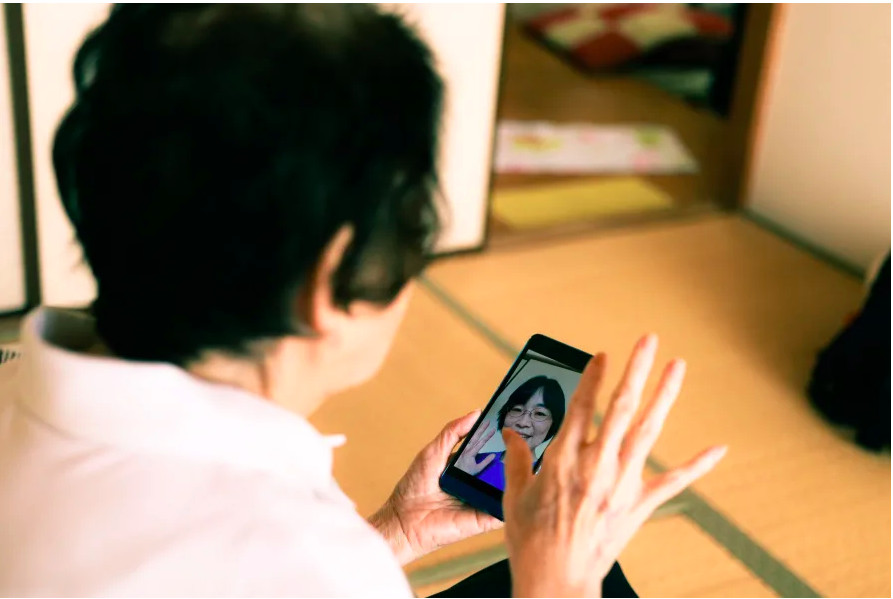

But there have been some positives that we can build on: with support, many older adults have been able to successfully embrace technology such as telehealth.

Nursing homes have been using technology to connect residents with their families.

One study of the 2003 SARS epidemic in Hong Kong suggests that older adults are more able to adapt and cope in a crisis than younger adults. This resilience and ability to adapt is something we can all learn from and gives us hope for the future.

Although anxiety is the most common type of mental health condition and there is effective treatment available – it is still a huge challenge to encourage people to seek help.

Stigma is still a major barrier, as is anxiety manifesting as physical problems such as headaches, fatigue or dizziness, so that it lives in us without a name.

Clinicians should also be on the alert for anxiety symptoms, which are even more common than anxiety disorders, and can have a significant impact on an individual’s life.

Health & Medicine

Bonus Episode: Life Beyond Coronavirus: The Expert View

Research is needed to work out how we can better identify anxiety and break down the barriers so that people can access effective treatments that will make a real difference to their lives and their community.

The team of clinicians and researchers at the Academic Unit for Psychiatry of Old Age at the University of Melbourne, Melbourne Health and St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, are hoping to make a difference in this area.

An example is the EXercise for Cognitive hEaLth (EXCEL) project funded by the Melbourne Academic Centre for Health (MACH).

This project aims to empower mid and late-life adults with anxiety and depressive symptoms to implement Physical Activity Guidelines, which have been developed by our team after a review of the research, that aim to reduce their risk of developing dementia as well as improving their mental and physical health.

Focusing on older adults’ mental health, particularly anxiety, will lead to a better life for many people in our community, and help us to avert a pandemic of anxiety.

*Joan is a fictional character used as an illustrative example.

Banner: Getty Images