Politics & Society

Is Europe heading for divorce?

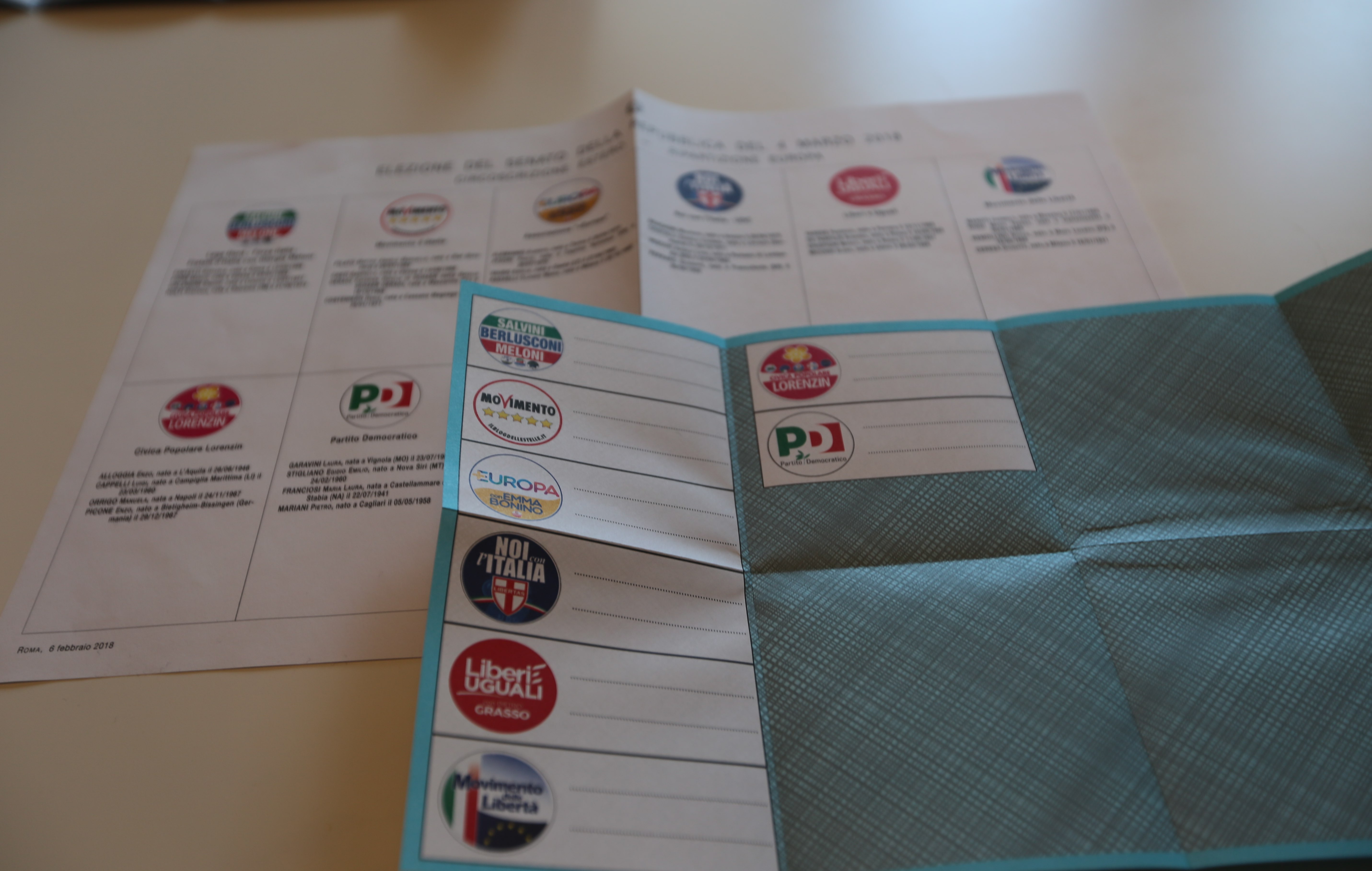

Italians head to the polls for the country’s General Election under a new electoral system amid anti-immigration sentiment, promises of cash for retirees and proposals of a new currency

Published 1 March 2018

Italians vote on Sunday to elect a new government as well as a new prime minister, and it’s become one of the most unpredictable political contests in decades.

With polls indicating no party will be able to form government in their own right, several alliances have already formed.

Voters on March 4 will have three main choices:

A centre-left coalition led by the Democratic Party (DP), headed by ex-Prime Minister Matteo Renzi

A centre-right alliance with controversial 81-year old tycoon and former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi at its helm, although he is currently barred from public office because of tax convictions (should he win, Berlusconi will challenge his ban on the grounds that his crimes were committed before the law implementing the ban was put in place)

The anti-EU 5 Star Movement (5SM) led by 31-year old Luigi di Maio (but closely monitored by its founder, Beppe Grillo who for legal reasons cannot enter parliament)

There are, of course, many other parties competing for the Italian votes, and the never-ending process of party splits, mergers and name changes is mind-boggling for outside observers.

Recent polls suggest a high proportion of undecided voters, with Berlusconi’s centre-right alliance currently tipped to emerge as most successful.

A major source of uncertainty is that this will be the first election held under an electoral law enacted only last year. The new system, known by its nickname Rosatellum bis, is a mixed-member proportional system with roughly one third of parliamentary seats awarded on a first-past-the-post basis and the remaining two-thirds allocated proportionally.

Under this new electoral system, voters will select all 630 members of the Chamber of Deputies and all 315 members of the Senate of the Republic.

Berlusconi’s centre-right alliance includes his own Forza Italia, as well as the hard right northern regionalists, Northern League, and ex-fascist, Brothers of Italy.

Both of these parties are notoriously anti-immigrant and have gathered some support due to an influx of illegal migrants and refugees, mainly from Africa, that Italy has struggled to manage while dealing with its own economic and political issues. The recent shooting attack on African migrants in Macerata by an extreme right-winger has only fuelled passions on all sides.

Berlusconi, sensing an opportunity for votes and the need to make sure his party remains the largest in the right alliance if it is to lead it into government, has promised to expel 600,000 illegal immigrants.

But there are other issues as play here.

5SM and other parties are calling for the repeal of a number of hard-fought economic reforms on labour law. Berlusconi also knows how to work the populist vote and, in particular, understands the electoral desires of Italy’s ageing population.

He is targeting retirees and the poor by promising €1,000 (around A$1500) monthly incomes. The 5SM is only promising €780 (approximately $1200), while the Democratic Party is only offering an increase in the minimum wage.

Politics & Society

Is Europe heading for divorce?

The unexpected size of the right-wing victory in regional elections in Sicily at the end of 2017 has also given Berlusconi and his populist message a big fillip. He’s also been helped by the falling popularity of the current centre-left government, led by the Democratic Party, and concern by many voters about protest party 5SM’s ability to govern nationally.

Anti-European sentiment is a significant issue, especially in relation to the Euro which has tied Italy’s economic hands, because it can no longer devalue the lira as it once did to maintain competitiveness with Germany and France.

As a result, some of the major parties are now promising a dual currency system: the Euro alongside a national currency.

The 5SM once took a hard anti-Europe stance but has softened in recent months, and the chances of a so-called ‘Italexit’ are unlikely – the difficulties of the Brexit experience have helped to temper public opinion on this matter.

Despite all the problems, Italy is too dependent on integration within the EU to consider a complete withdrawal.

If forming a government comes down to one or two votes in parliament, Australia could play an unexpectedly critical role in the outcome.

Italian citizens resident abroad have full voting rights and are assigned a number of overseas seats (12 deputies and six senators).

Australia elects two members to parliament (one deputy and one Senator) as part of a huge electorate that spans Africa, Asia, Australia and Antarctica, but which it dominates given the sheer number of Italians living in Australia.

Both seats are currently held by Australian-based representatives of the Democratic Party.

This article was co-published with the University of Melbourne’s Election Watch.

Banner: Getty Images