Politics & Society

How can we open up Melbourne while tackling disadvantage?

Australian cities are integrating the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals into their own COVID-19 Recovery Plans, using local action to drive global sustainability

Published 30 October 2020

Cities have been the epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic, with little discrimination between more and less developed urban environments.

More than 95 per cent of total cases have occurred in urban areas, while a lack of access to safe drinking water and health services continue to heighten risks for the more than one billion people living in urban slums and informal settlements around the world.

Poorer and more vulnerable urban dwellers in some of the world’s most globalised cities have also suffered disproportionately – from Melbourne and New York, to Singapore.

Politics & Society

How can we open up Melbourne while tackling disadvantage?

Cities are also at the core of the global sustainability crisis.

October 31 is recognised by the United Nations as World Cities Day, with the 2020 theme Valuing Our Communities and Cities.

In 2015, the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was heralded as a comprehensive and ambitious blueprint for “transforming our world”.

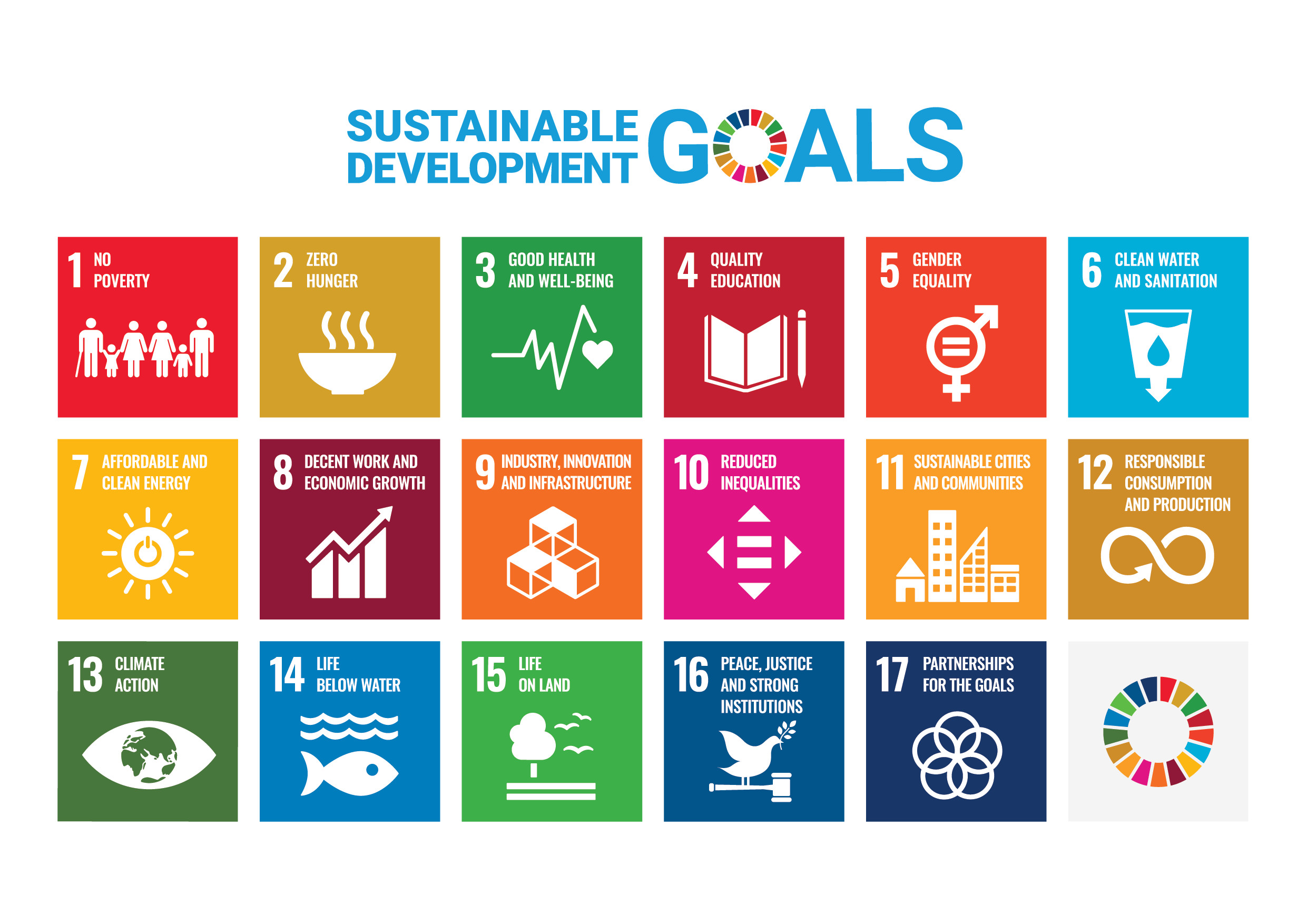

Agreed by all 193 UN Member States, the 2030 Agenda set out a holistic framework of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 associated targets.

Critically, the SDGs were designed to be applied to all Member States, reflecting differing strengths and weaknesses in sustainable development across the ‘developed’ Global North and the ‘developing’ Global South.

As we enter the Decade of Action on the SDGs, the window is rapidly closing on a once-in-a-lifetime chance to rethink, rewire and repurpose our urban environments for a more sustainable future for everyone.

Even before COVID-19 had become a global pandemic, the 2030 Agenda was tracking poorly. At the end of 2019, a global snapshot of progress towards the SDGs showed that for even the most fundamental of development objectives – like ending poverty – the world was ‘off track’.

Other measures were found to vary by region and country grouping. For example, achievement of targets relating to urban air quality in country groupings as diverse as those of the OECD and Pacific Island Small Island Developing States were offset by declines in other groups such as those of Sub-Saharan Africa as well as Central and Southern Asia.

In the intervening ten months, COVID-19 has set global development back decades.

Obvious impacts are reflected in headline figures, like the addition of an estimated 71 million more people suffering extreme poverty in 2020 alone.

Even the measurement of progress towards the SDGs is under threat.

Data collection for both national planning processes and the measurement of progress towards the SDGs (in the form of 231 unique indicators) is primarily undertaken by the national statistics offices (NSOs) of each country.

But a survey of NSOs by the World Bank and the UN found that 72 per cent had partially or fully stopped face-to-face data collection in July (down from 96 per cent in May), with more than half unsure of when data collection would resume.

This compounds major shifts in these indicators due to COVID-19, with the pandemic sending measures, like unemployment, off the charts and drastically shifting patterns of urban movement and industrial activity.

Politics & Society

Celebrating 75 years: The UN’s past and future

Despite this, the urgency of meeting the goals has, if anything, increased. More people are being left behind than ever as a result of the pandemic’s economic impacts.

As of 2015, four billion people lived in cities, making up 54 per cent of the world’s population.

By 2030 this figure is projected to grow by a further one billion people, with the bulk of this growth occurring in the Global South.

Although cities only cover three per cent of the Earth’s land mass, they generate 80 per cent of global economic output and, relatedly, account for more than 70 per cent of global energy-related greenhouse gas emissions.

So any transformative global agenda must be localised within our current urban fabric, but the local decision-making for the ongoing expansion and renewal of cities must also driven by these wider sustainable development considerations.

In the 2030 Agenda, this process of ‘localisation’ is reflected not only in the inclusion of an ‘urban’ Goal (SDG11), but also in linkages across an array of urban-relevant targets and indicators throughout the 17 SDGs.

These urban-relevant targets exist across each of the SDGs (see Figure 1).

Within SDG6, Target 6.1 – to achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all – is as problematic within urban slums as it is for remote and rural populations. Emissions reduction is also exclusively addressed through targets within SDG13, Climate Action, and SDG7, Affordable and Clean Energy.

Environment

Building cities for a changing climate

In August 2020, an alliance of Australian businesses and non-government organisations, including the University of Melbourne, asked the Federal Government to use the SDGs to frame its COVID-19 recovery.

Although the SDGs are acknowledged within the Federal Government’s COVID-19 Development Response and are mapped within country-level performance frameworks, implementation beyond the submission of a Voluntary National Review in 2018 has been limited.

Even before the pandemic, no data had been identified to report against SDG11 indicators, for instance, on the Australian Government’s SDG Reporting Platform since its launch in mid-2018.

Instead, Australian cities have taken to integrating the SDGs into their own COVID-19 Recovery Plans, as well as wider strategic planning processes.

The localisation of the 2030 Agenda follows in the footsteps of other areas led by cities and city networks, such as climate action and resilience thinking. More than 200 cities have signed up to New York City’s ‘Voluntary Local Review (VLR) Declaration’, committing to localise the SDGs in partnership with their citizens.

Regional guidelines and data standards are consolidating methodologies, enabling benchmarking and shared learning between cities.

Central to many of these localisation efforts have been partnerships with independent research institutions, like universities. Examples of include VLRs developed for cities as diverse as Bristol in the United Kingdom, Argentina’s capital Buenos Aires, Cape Town in South Africa, and Shimokawa, Japan.

Politics & Society

New foreign relations bill puts ‘city diplomacy’ at risk

Building on these experiences the University of Melbourne and the City of Melbourne have partnered to take the ‘VLR’ process a step further.

In addition to the City integrating the SDGs into their own COVID-19 Recovery Plans, the SDGs for Melbourne project is developing a strategic prioritisation framework for the City, informed by progress towards all 17 SDGs.

By aligning indicators with comparable SDG-localising cities in and beyond our region, as well as integrating the SDGs at a target level within the City’s own organisational structure, the project will set out a new best practice model for localising the 2030 Agenda.

As noted by the former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, “our struggle for global sustainability will be won or lost in cities”.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have made the achievement of Agenda 2030 harder, but it has also made clear how critical our cities are if we are to truly ‘leave no-one behind’.

Banner: Shutterstock