Exposing the hepatitis B virus

A new method detecting the ‘master blueprint’ of hepatitis B will help researchers globally test potential medicines to discover a cure for the virus. Oh, and there’s a love story in this episode too

Published 13 November 2019

The hepatitis B virus causes liver inflammation that, despite treatment, still leaves people at greater risk of developing liver disease and cancer. While it can be effectively vaccinated against, there is no cure.

Researchers Professor Peter Revill and Dr Thomas Tu are on front line of global efforts to find a cure; helped by Dr Tu developing a new method to better detect the virus’ ‘master blueprint’.

For Dr Tu, who was diagnosed with the disease as a teenager, finding a cure for Hep B is personal.

“I wasn’t given much information, just that you will have this for the rest of your life, and that was it. You may get liver disease down the track,” recalls Dr Tu.

“After that I was a bit despondent, as you can imagine, but then “I thought what is this”? And so I went online and started really looking up what hepatitis B was and I accrued all of this knowledge and realised I could do something.”

In fact, Dr Tu’s research in part led him to meet his now-wife.

Professor Revill says Dr Tu’s new method could be a “game changer” in terms of developing and testing new drugs.

“There’s many things we still don’t understand about the virus lifecycle or replication cycle, and we still cannot cure it,” says Professor Revill.

“The most important thing we need to do is develop a finite cure that people can take some pills for a short duration and not have to take pills for the rest of their life, and that inspires me every day.”

Episode recorded: September 30, 2019.

Interviewer: Dr Andi Horvath.

Producer, editor, audio engineer: Chris Hatzis.

Co-production: Silvi Vann-Wall and Dr Andi Horvath.

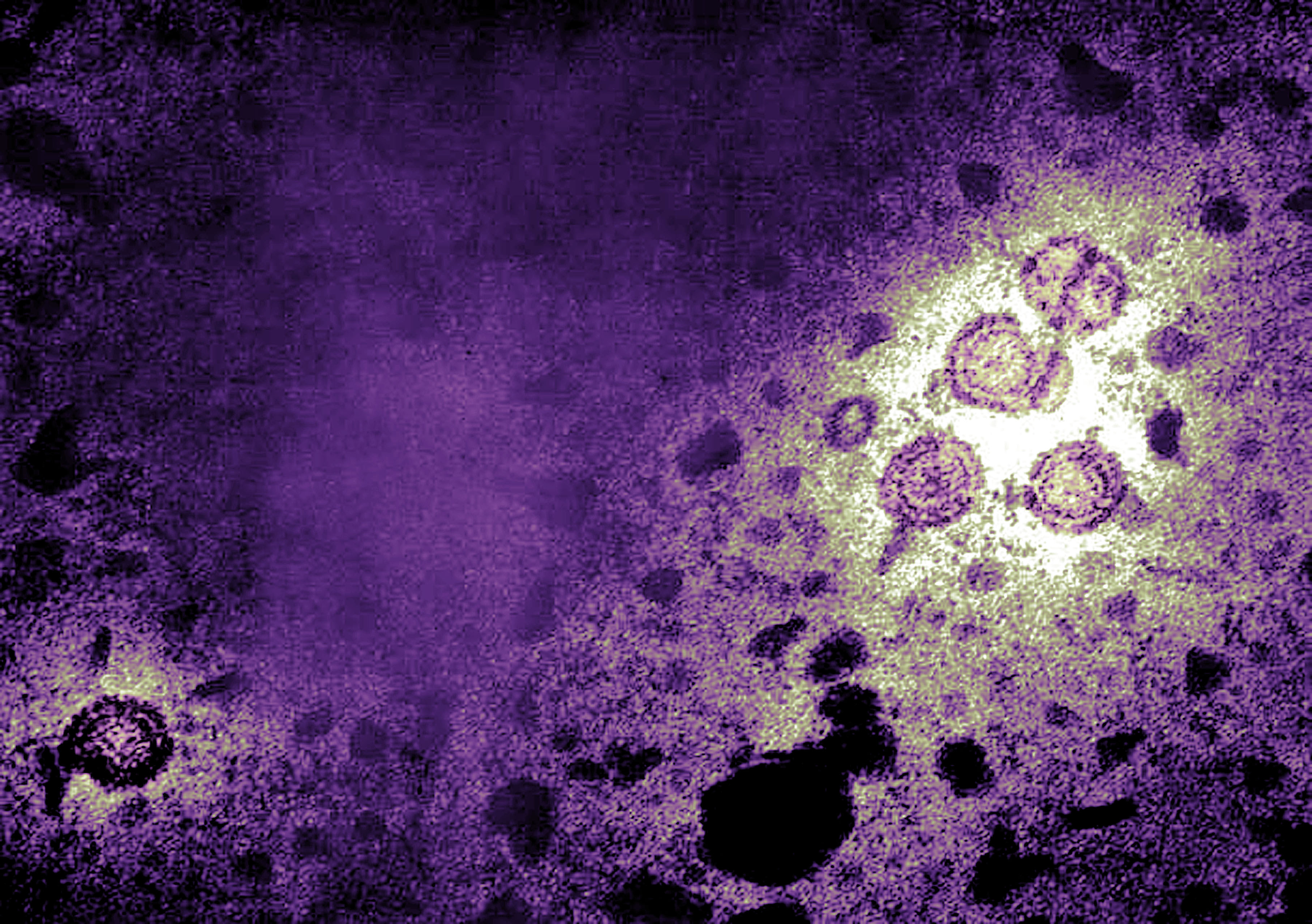

Image: Transmission Electron Micrograph of Hepatitis B virus particle. Getty Images

Subscribe to Eavesdrop on Experts through iTunes.