Sciences & Technology

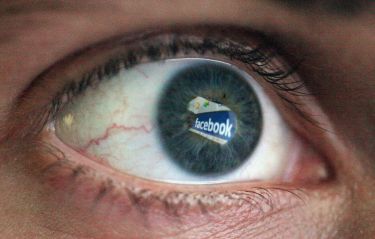

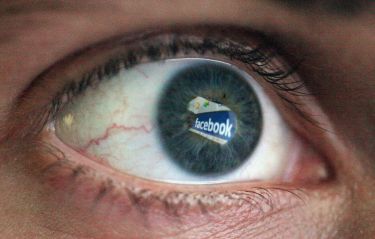

Data privacy and power

From the Occupy Movement to internet freedom legislation in Brazil, ‘technopolitical nerds’ are making their mark worldwide

Published 24 October 2018

Sciences & Technology

Data privacy and power

Politics in the digital age is increasingly shaped by tech-savvy activists; the Edward Snowdens and Julian Assanges of the world.

But it’s when these ‘nerds’ join with others, that true change happens - like Spain’s Indignados movement becoming a force in the country’s mainstream political system.

Dr John Postill discusses his new book The Rise of Nerd Politics in this new episode of Eavesdrop on Experts.

Episode recorded: September 4, 2018.

Interviewer: Steve Grimwade.

Producer and editor: Chris Hatzis.

Co-production: Dr Andi Horvath and Silvi Vann-Wall.

Banner image: Getty Images

Subscribe to Eavesdrop on Experts through iTunes.