Arts & Culture

Preserving precious Indigenous languages

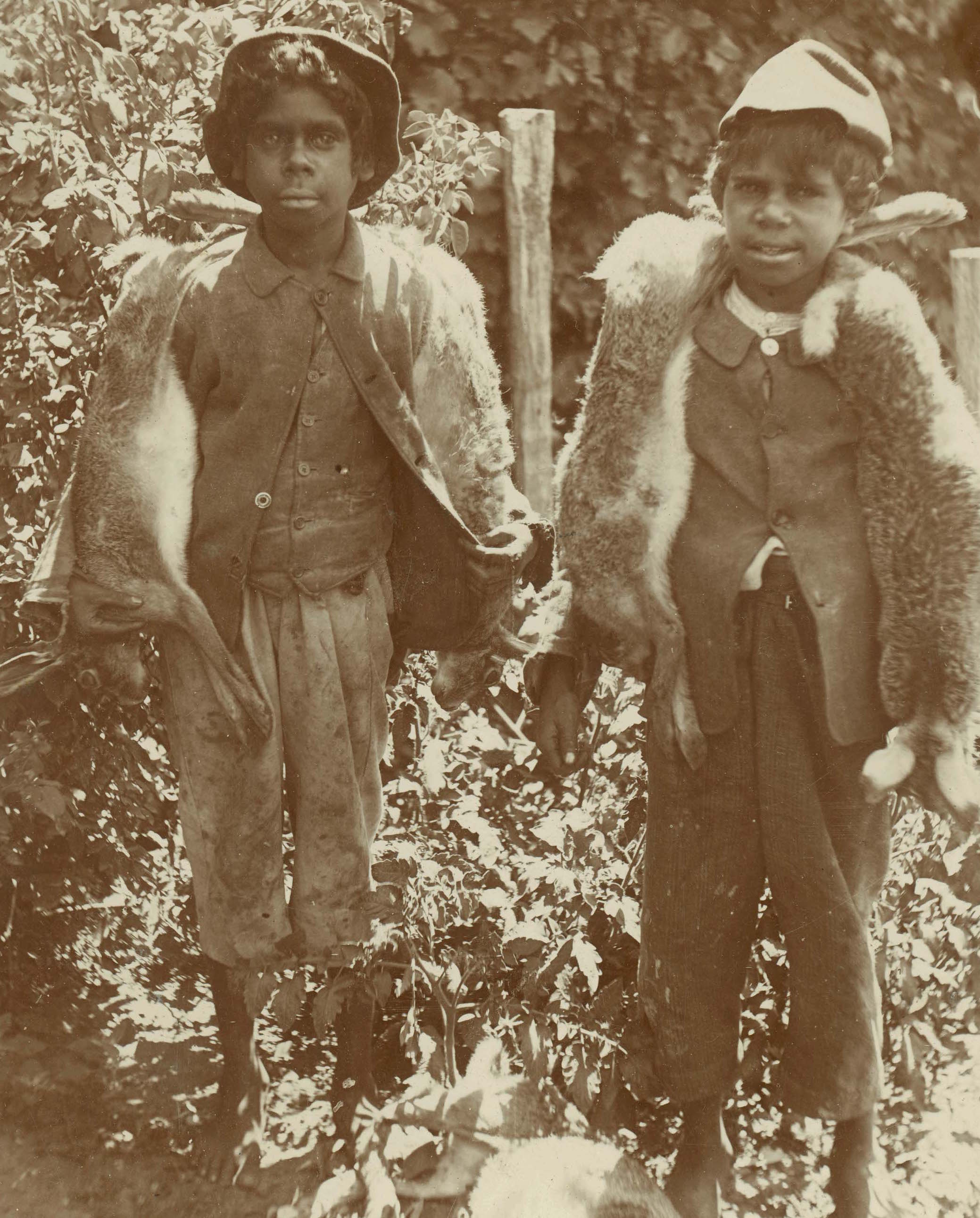

Connecting faces in 19th Century photographs to their contemporary Aboriginal descendants can tell a new history

Published 30 November 2016

Content warning: Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Australians are advised that this web page contains the names and images of people now deceased.

The faces in the photographs look out from over a hundred years ago, dressed in their Sunday best – Aboriginal people growing up on a church mission in Victoria’s Gippsland. They look back from a time when the State forced them into regulated lives on missions and took away their children in the name of assimilation.

“You can easily look at these photos and think what pitiful lives, but if they could speak we would hear stories of achievement, determination and resistance,” says writer, photographer, and oral historian Dr Sharon Huebner.

Those stories of achievement and determination may not have been recorded, but Dr Huebner says they can still be found in the experiences of their descendants if the photographs become the agent for combining history, memory and connection.

In an ambitious project to inject Victorian Aboriginal voices and perspectives into a history that has long ignored them, Dr Huebner is using the University of Melbourne Archive’s Strathfieldsaye collection of 19th century photographs to connect the faces in the photographs with their contemporary families.

“The work of researchers like Dr Huebner is very important,” says University of Melbourne archivist Stella Marr. “The human face is both very complex and powerful, so for relatives to connect with a photograph, meet their direct family, or community, in the eye can be a source both of pain and also a site of potential healing.”

Dr Huebner hopes that by connecting contemporary families to a history they may often be unaware of, she will be able to bring together the lost Aboriginal experiences of the past with the memories of current Stolen Generation survivors and their families. By doing so, she says the voices of the present can enliven the history of their ancestors and counter the passive role they have been relegated to in the history books.

“Photographs of ancestors represent more than colonial injury,” says Dr Huebner, a Hugh Willamson Foundation Fellow at the University of Melbourne Archives. “If the photographs can go back to the descendants and elders in the Koorie community then their own memories of growing up on a mission become the method for reviving lost memories of ancestors. We can better imagine the cultural lives of these people in the photographs.

“So even though the lived memories of these people are not handed down, the community can tap into their own knowledge to more fully interpret what the photographs represent in the context of kinship and ideas of belonging.”

The project is an extension of Dr Huebner’s previous work in reconnecting Aboriginal families in Victoria and Western Australia to their ancestor Bessy Flowers (1849-1895) who lived at the Ramahyuck mission in Gipplsand, Victoria. Bessy is unique in that her letters have survived as well as historical photographs of her. In partnership with Bessy’s kin Ezzard Flowers, a Wirlomin Minang Noongar man from Western Australia, Dr Huebner has written and produced a unique multimedia story of Bessy, No Longer a Wandering Spirit that for the first time tells her story through the lived memories of her Koorie descendants and Noongar relations.

Bessy was sent away from her ancestral Minang country in the Great Southern of Western Australia at 18 and sent to live at Ramahyuck where she eventually married a Koorie man from Ebenezer Mission in north-western Victoria.

A skilled teacher and pianist, Bessy never returned to the west and spent the latter part of her life battling missionary and colonial authority to keep her family together.

“One of the biggest shifts that needs to happen in this nation is to let Aboriginal people negotiate these histories on their own terms and to intervene in the history of their ancestors with their own voices,” says Dr Huebner.

“These photographs are too easily viewed as representations of a dying race of people who were powerless, when Bessy’s letters reveal a strong and determined person. But it is rare for the words and views of Aboriginals to be preserved, so we need to fill that gap in our knowledge by making space for the Aboriginal experience and the Aboriginal voice.”

The Ramahyuck mission was originally carved out of the Strathfieldsaye station that was bought by William Henderson Disher in 1869. For the Disher family, Ramahyuck became a place for social outings and churchgoing. William’s son Clive eventually married the daughter of the Reverend. When Clive bequeathed the estate to his alma mater, the University of Melbourne, the photo collection came with it.

“Many of these photographs were created by professional photographers such as Frederick Cornell – who in his 1850s montage ‘Aboriginal Mission Station, Ramahyuck’ presents individuals as nameless examples of their race – representing the ‘success’ of the mission,” says Ms Marr. “The story less often told is that the Disher Family have many of these photographs in their personal photograph album where they have been lovingly colour tinted by hand, adding blue to ribbons or pink to flowers. The people in these photographs are also not only named, but their relationships are documented.”

For example, on the verso of a photograph of a young Aboriginal woman in the collection someone has annotated ‘Bridgette – Stephen’s love’.

“Generalisation suffocates histories – it is these unique, individual examples which we must work to give voice to – whether that comes from archival sources or community engagement projects,” says Ms Marr.

The Strathfieldsaye records and photographs have been used by many other researchers over the years including most recently in Rachel Perkins’ film The First Australians; but Ms Marr says what is unique and exciting about Dr Huebner’s work is that it is bringing together community knowledge to enrich and expand the archival records and our knowledge.

Connecting the Strathfieldsaye photographs to contemporary descendants will be a major detective task, but Dr Huebner has the advantage of having worked for over 15 years helping to connect Koorie people to their lost family histories. She will also use the genealogies compiled by anthropologists, including the extensive fieldwork in Victoria of Diane Barwick who died in 1986, and whose research is now held in the State Library of Victoria.

“If the photographs are informed by a lived experience, even if it is remote from when the photographs were taken, a different perspective can be brought to them. One perspective will be that life was indeed hard on the missions, but families will also bring to the photographs their own positive memories of childhood and this supports an understanding that the people in the photographs would also have had similar empowering experiences,” Dr Huebner says.

Arts & Culture

Preserving precious Indigenous languages

“This isn’t to diminish the reality of our colonial history and its impact on Aboriginal lives, but it allows Aboriginal people to weave into their history a narrative of pride and dignity that they can use as a foundation to look forward and imagine futures they can determinedly step into.”

But time is running out to retrieve the stories of those who grew up on the missions.

“The opportunities are diminishing because as elders pass away we risk losing those stories of growing up on a mission. These stories need to be passed on to younger people in order to generate intergenerational bridging between these histories bound by the strength and resilience of kinship.”

“If you believe your culture is shattered and scattered and finished, or your language is gone, then you are a dead man walking. But if you believe you can reconnect to your language and your culture, you become empowered.” – Ezzard Flowers in No Longer a Wandering Spirit.

No Longer a Wandering Spirit: the story of Bessy Flowers will be presented at the State Library of Victoria on Thursday December 1 at 6pm.

Banner Image: Mena Cameron (daughter of Bessy Flowers), Lydia Gilbert and Annie Harrison, c.1898, Strathfieldsaye Estate Collection (1976.0013). University of Melbourne Archives, PA.198 p.9 (Ramahyuck Album 8.4.9)