An astrophysicist meets The Martian

Dr Katie Mack says there’s science and there’s fiction in Ridley Scott’s new blockbuster

Published 24 September 2015

The Martian can be viewed in a few different ways.

You could say it’s an action/adventure/suspense movie, and view it as a series of nail-biting is-this-going-to-work-or-will-all-be-lost moments. You could watch it as a love story to human exploration, and be inspired by ingenuity and persistence in the face of incredible odds.

You could just be a space enthusiast and marvel at the ability film has to transport us off our own planet and onto alien worlds. You could watch it as a scientist and crane your neck to capture every bit of tech, every calculation, and every view of the Martian surface.

Or you could be like me and go for all of the above.

I want to go to Mars. I’m pretty sure I have always wanted to go to Mars, and if NASA were offering a trip to Mars, I would go. It wouldn’t have to be a return trip. Getting there would be enough for one life, as far as I’m concerned.

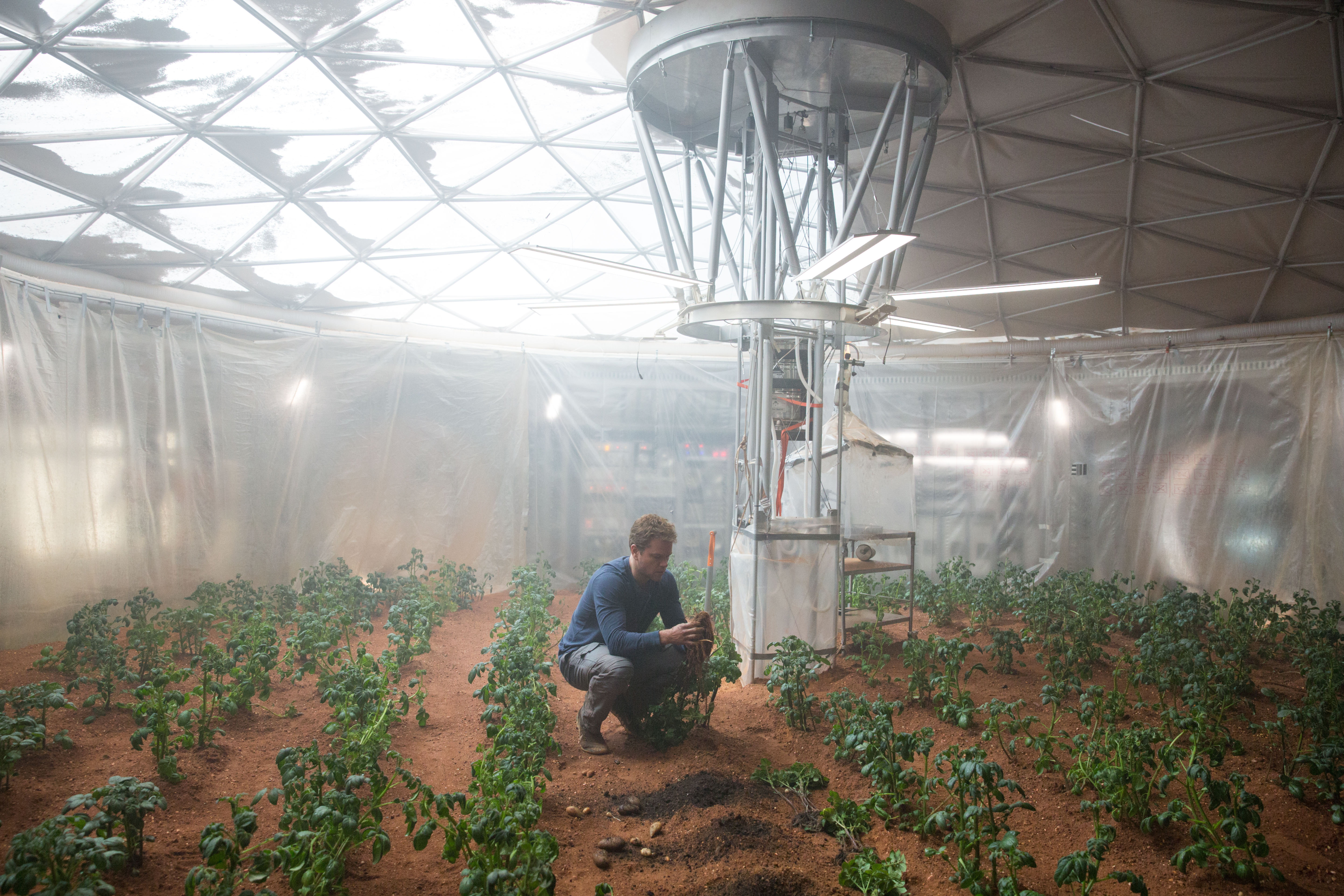

So of course I devoured Andy Weir’s book, The Martian, in which a lone Mars astronaut is injured in a dust storm, mistakenly left for dead by his crew, and thus forced to try to find a way to survive long enough to be rescued. As a musing on the practical problems of trying to live on Mars when ABSOLUTELY EVERYTHING is going wrong, it’s a fun read. And it caters unabashedly to those of us who want to know exactly what proportions are needed to make water from rocket fuel and in what way it’s likely to go spectacularly wrong if you try it.

When I heard that the book would be made into a movie, my first thought was ‘OMG YES MARS’ and my second was ‘I really hope they don’t cut all the science out’.

The good news is they didn’t cut all the science out. They skip most of the calculations for (I grudgingly admit) obvious reasons, and the techy discussions about water reclaimers, battery efficiencies, and thermal regulation are glossed over or left out.

But there are plenty of problems to be solved, and we get to vicariously enjoy astronaut Mark Watney (Matt Damon) attempting to survive – or as he says, to “science the s*** out of it”. And we get to see the Martian landscape in all its sandy, rocky, rusted glory.

With two Martian rovers and three orbiters currently active on or around Mars, there is more than enough real Martian imagery to create incredibly accurate Martian vistas and skyscapes on screen. The movie does not disappoint, letting us revel in the stark beauty of the Red Planet with long aerial shots, ground-level views to the horizon, and some gorgeous renderings of the planet from orbit. Watney mentions going out for walks just to experience being on this alien world, and as a viewer it’s hard not to wish you were there with him, and to feel like maybe in a limited way you are.

Mars aficionados will appreciate the little details. The moons are often in shot, and unlike in some other recent Mars-based movies (I’m looking at you, John Carter), they’re not round. Mars’ moons Phobos and Deimos, which were thought to be captured asteroids but are probably the result of a collision, are too small to be rounded out by gravity, and it’s nice to see them realistically lumpy on film.

There’s also some nice Martian weather, with wispy clouds and dust devils, both of which are regular features of the Martian environment. That said, Mars weather is sometimes cranked up to 11. There is a lightning-filled dust storm (not impossible but very rarely observed) and there are so many dust devils they appear to be taking over the planet. Real Martian dust devils only happen around the middle of the day, in the spring and summer, although they can be impressively huge – stretching up to 10 kilometres.

One of the least accurate aspects of Mars surface science, according to a friend of mine who maps Mars for a living, was the maps. We already have better maps than Watney uses 30 years in the future.

The spacecraft and tech were fun to see. The ‘Hermes’ spacecraft has a rotating ring that simulates gravity on the long journey to Mars and back, and its modular design makes it believable that it was assembled in orbit in preparation for the mission. The ‘Ares’ missions are arranged in stages, with supplies and vehicles sent to Mars years ahead of the astronauts. They have supplies to build their habitat (called the Hab), rovers, and an ascent vehicle, making it possible to land the human component of the mission on its own.

This is an extremely sensible and realistic way to set up a Mars mission. They even have a getaway car - the ascent vehicle - ready to go.

Landing on Mars is hard – its gravity is too strong to land with retro-rockets like the Apollo astronauts did on the Moon, but its atmosphere is too weak for the heat shield/parachute/soft-landing rocket combination used by the Soyuz when returning from the Space Station.

The more stuff you can get to the surface without worrying about people’s safety the better.

Some accuracy was jettisoned for creative purposes, of course. Like the book, the film asks us to believe that the mission’s surface rovers can’t communicate directly with Earth – this is unlikely (even the current robotic Mars rovers can talk to Earth), but both the book and film would be way less interesting if it were corrected.

Perhaps the most striking science fudge is how dry Mars is in both the book and movie. Shortly after the book came out, the Curiosity Rover found that the Martian soil has a huge amount of water locked up in it, and this water could probably be extracted.

Of course, it’s more exciting to make water out of rocket fuel.

The movie stuck fairly close to the overall story arc of the book, though it had a few simplifications, with fewer life-threatening disasters and one long scene towards the end that had me cringing in its over-the-top action-movie antics.

The depiction of the NASA scientists and the Ares crew was far less reliant on stereotypes than most films I’ve seen, and the cultures of the major organizations involved (the main NASA headquarters and the more research-lab style Jet Propulsion Laboratory) were pretty faithfully depicted.

It was clear that the filmmakers spent time with NASA and got a feel for how the space agency works.

There were the usual shortcuts in depicting space missions – why don’t movie astronauts ever use tethers on spacewalks? – and a few moments that made me laugh out loud – at one point an orbital dynamicist checks a calculation by plugging a cable from his laptop into a supercomputer instead of submitting a job to the queue like a normal human being.

But for the most part, the scientists seemed like scientists and the astronauts like astronauts. I was very glad that the film toned down Watney’s frat-boy personality (they omitted the “boobs” joke he makes in the book, for instance) and did a better job depicting female characters than the novel.

One error the movie didn’t correct was the use of the term “manned” to talk about ongoing human spaceflight missions. NASA is already officially phasing this term out, and I’d be shocked to see it hanging on in the middle of the 21st century.

Making an engaging feature film out of a book aimed mainly at hardcore space nerds was always going to involve trade-offs, but those the film makes mostly seem to work. We get to join in the problem solving and imagine ourselves facing incredible odds while alone on a planet, even if we don’t get enough information to do the maths ourselves. We get treated to an absolutely gorgeous spacecraft and a vision of Mars travel that looks positively (if perhaps implausibly) luxurious.

And we get to see Mars the way Watney sees it, with all its untouched beauty and indifferent menace.

I could go on and on about little science nitpicks, or, equally, enthuse for hours about all the little things they got right. But mostly I just want to see it again, to spend some time in a future where human spaceflight is thriving, celebrated, and seemingly just within reach.

Banner Image: 20th Century Fox