Life of the party

Germaine Greer made a splash when a magazine ran a series of stunning pictures of her - now some of them are being exhibited

Published 7 December 2015

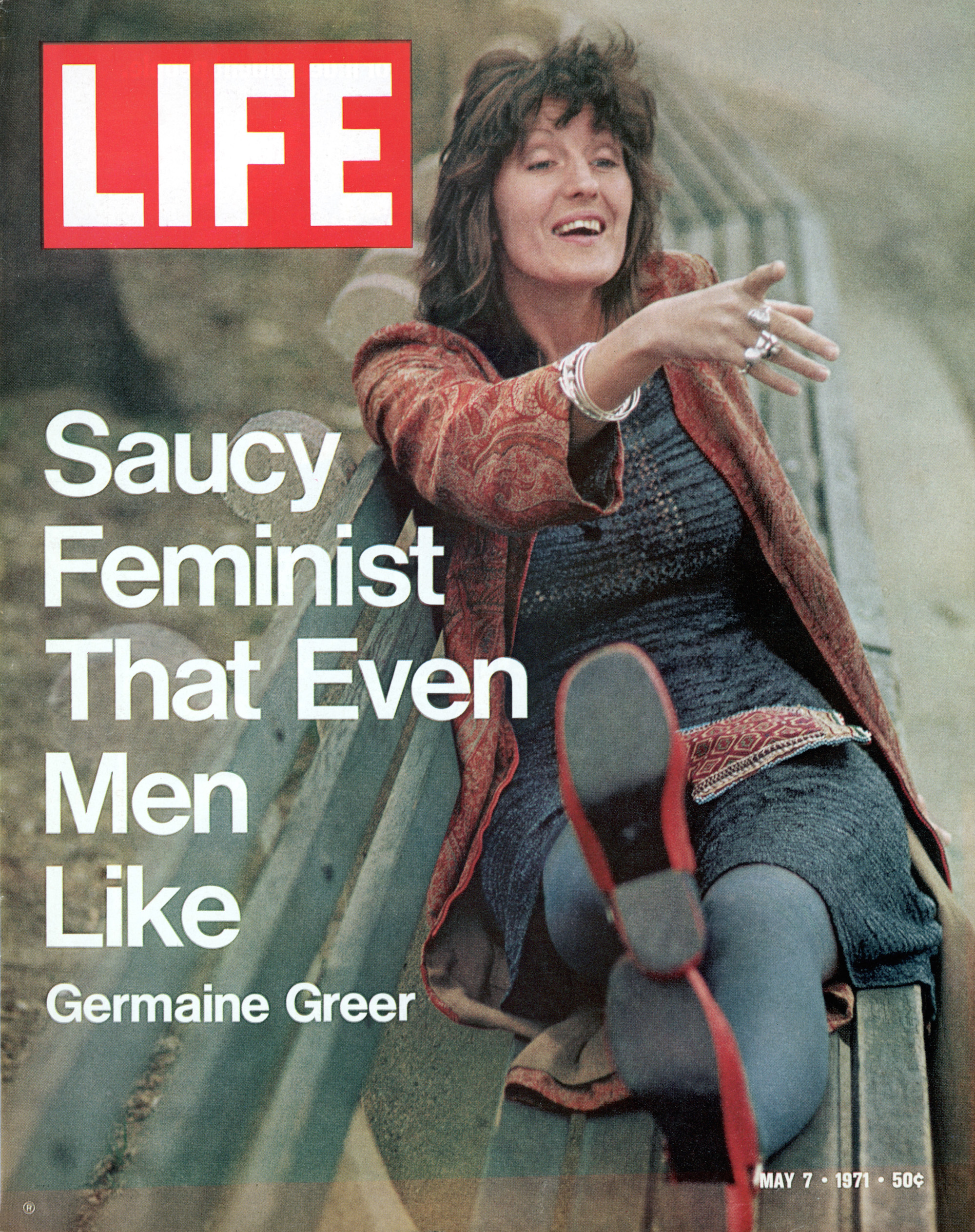

On 7 May 1971 Germaine Greer made the cover of LIFE magazine.

In photographer Vernon Merritt’s cover shot, the “saucy feminist that even men like” is sitting on a park bench, laughing, her right hand pointing at someone behind the camera. Silver bangles slip down her arm towards the sleeve of her home-made paisley frock coat.

Inside, LIFE published five more photographs to go with reporter Jordan Bonfante’s profile. These images – shot by leading photojournalists Terence Spencer and Harry Benson in England and the United States – could almost be of five different women. Greer is portrayed as muse, academic, forager, peace activist and the hippest of literary stars.

The LIFE cover and photo shoots acknowledged and amplified Greer’s sudden celebrity in the US, paying homage to the 32-year-old writer’s skill as a self-described “media freak”, a chameleon with a charisma and variety of personas to rival a young Bowie.

After the shoots, LIFE magazine gave Greer an album of 57 mostly unpublished black and white photos taken by Benson and Spencer. Eleven photos from the album are now on show at the Ian Potter Museum in Melbourne as part of the My Learned Object exhibition.

This album is one of the many treasures in the Germaine Greer Archive, which was purchased by the University of Melbourne in 2013 and is currently being catalogued and processed to make it more widely available to researchers.

This world-class archive comprises 472 boxes of material relating to Professor Greer’s adult life from her days as an undergraduate at the University of Melbourne (she graduated with a BA Hons in 1959) to her purchase and rehabilitation of a rainforest in southern Queensland, a project documented in Greer’s most recent book, White Beech (2015).

The middle portion of the archive contains letters, ephemera, news clippings, diaries, index cards and typed and handwritten notes and drafts relating to conception, research, writing and reception of Greer’s most famous book, The Female Eunuch (1970).

This material provides a context for the LIFE album photographs. The images capture an astonishing few weeks in which Greer was transformed from a junior Shakespearean academic and minor media celebrity into the most famous feminist in the world.

Greer was awarded her PhD from Cambridge in 1968. She was a lecturer in 17th Century English literature at the University of Warwick and starred in a weekly Granada TV variety show with Kenny Everett (Nice Time, 1968-1969). She was also writing New Journalism-style pieces, including an especially fine obituary for Jimi Hendrix, for Oz and other underground British papers.

But she was unknown in the US until McGraw Hill decided to publish The Female Eunuch there. The pre-publication hype was such that on 20 April 1971, just a day after Eunuch was published, The New York Times ran a review headlined: “The Best Feminist Book So Far”. The book sold 61,000 copies in its first three weeks, sharing a spot on the New York Times best-seller list with Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock and Dee Brown’s Indian history Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee.

Greer herself was a sensation. “Six Feet Tall, Sexy and Brainy,” was one emblematic headline. “Erudition and eroticism” was another.

She arrived in New York on 6 April. On the 7th, the New York edition of Celebrity Information and Research Service (an pre-internet version of Gawker), billed her as its celebrity of the day, “an Oxford don who is also an underground queen … a Warwick University lecturer who is also an editor of Suck magazine … a PhD on Shakespeare who is also a TV and radio personality … an admitted lover of men who is also an anarchist among fem libs!”

Terry Spencer had already photographed Greer in England in March. Spencer snapped a serious, fine-boned Greer sitting on a paisley couch, Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe alight behind her; an academic cracking her students up in a tutorial; and a suede-skirted woman collected firewood in a forest.

Benson took over in America, portraying Greer as a staunch protestor at an anti-Vietnam War march in Washington and a giggling, girlish hippie snuggling up to filmmaker Dick Fontaine on a bed in New York’s Chelsea Hotel. He took pictures of Greer entertaining friends and admirers, including Australian-born rock journalist Lillian Roxon and actress Viva Superstar (Janet Susan Mary Hoffman) and her baby Audrey Auder.

On 30 April, New York’s radical chic set paid $25 each to see Greer and three other feminists debate Norman Mailer at the Town Hall. Susan Sontag and Betty Freidan were both there. “Greer did a Diedrich in slinky black silk and a fluffy fur,” Lillian Roxon wrote in a piece for the Sydney Morning Herald. “Mailer did a Burton (doesn’t he always)?”

LIFE came out a week later. The LIFE album commemorated the trans-Atlantic shoot. The album’s frontispiece says “From the Editors and Photographers of LIFE”. The plural is apt. Although the glossy magazine had reduced its circulation from 8.5 million to 7 million a week in 1971, it still listed 187 staff on its editorial page. LIFE had bureaux in New York, Washington, Los Angeles, Chicago, Paris, London, Bonn and Hong Kong. It employed nine copy readers, 16 layout journalists and 19 staff photographers. One of the dozens of staff writers was singer Martha Wainwright’s dad, Loudon.

Greer’s quick retort

Aside from being evidence of Greer’s extraordinary ability to shape shift, the LIFE album is also a reminder of photo-journalism’s golden age and the skills and budget that went with it, including hand printing analogue film in a dark rooms and being able to assign three photographers to one story. LIFE folded in 1972.

A week after LIFE appeared, “the saucy feminist” became the first woman to address the National Press Club in Washington and she opened her speech with an attack on press coverage of American women’s news, including breast cancer, the pill and child care centres.

Women had only been allowed into the club the year before and the gift Greer received indicated that integration had a way to go. She got a Press Club tie and quipped it would be useful “to keep my hair out of my eyes during demonstrations”.

Greer handled even the silliest question with typical panache. “If there were three people left on earth, you, Norman Mailer and Teddy Kennedy – which one would you choose?” one journalist asked.

“If I had to breed with either it might be just as well that the world came to a halt immediately,” she said.

Afterwards, the author was surrounded by admirers. Washington Post reporter Sally Quinn watched as a young woman lit Greer’s Camel cigarettes for her. “I’m a complete media freak,” Greer told Quinn and others.

“And the only reason I ever submitted to the commercialisation of Germaine Greer is to help women in the home, to raise the self-image of women, to spread the movement to the widest possible base.

“My aim was to demonstrate that everything could be otherwise and joyously otherwise.”

On 14 and 15 June, Greer guest hosted two episodes of the American Broadcasting Corporation’s late night Dick Cavett Show. One was on abortion, the other rape. Enraptured viewers wrote hundreds of letters and postcards in response. Greer received more fan mail than any other guest in the show’s history.

On the back of this success, a New York production company developed a pitch for The Germaine Greer Show, a 26-episode series. The treatment for the first one involved Germaine Greer interviewing Woody Allen. Another possible guest was Muhammad Ali. One can only feel sorrow that this new opportunity to commercialise Germaine Greer was never taken up.

Eleven black and white photographs from the LIFE magazine 7 May 1971 cover story on Germaine Greer are on show in My Learned Object: collections and curiosities, Ian Potter Museum of Art, 4 December 2015 – 14 February 2016.

Banner Image: Germaine Greer in 1972. Picture:Hans Peters/Anefo - Nationaal Archief Fotocollectie Anefo. This picture, which has been modified, is not part of the exhibition.