10 great books you should read in 2017

Looking to shake up your reading habits? Let the University of Melbourne introduce you to some classics.

Published 3 February 2017

Most of us follow the same path in the library or bookshop, choosing the latest novel by our favourite author, or something else from the same genre.

But the University of Melbourne’s 10 Great Books is here to help you step out of your literary comfort zone.

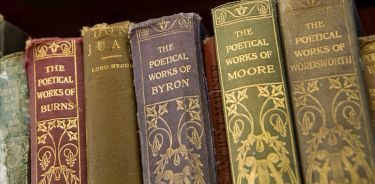

Ten distinguished scholars from the University have recommended books they believe deserve a reader’s attention, from ancient texts to modern classics.

Associate Professor Tim Lynch, director of the University of Melbourne’s Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, says the books chosen give an insight into the enduring power of the written word.

“Great books remain basic to humanity and history – they were revolutionary 1000 years ago and remain so,” he says.

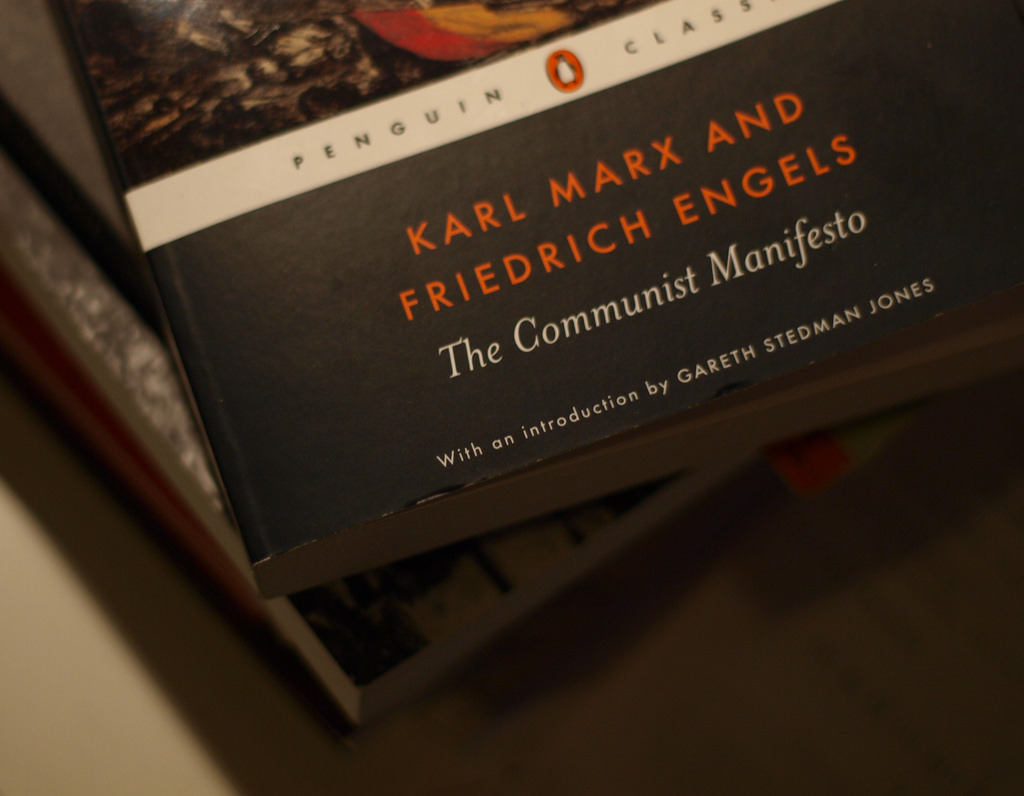

“Books remain central to political debate, from the Communist Manifesto, which in some ways defined the terms of political debate for over a century, to the US Constitution, which President Trump is currently testing.

“Scientific revolutions usually take place in books, from Newton to Darwin, and religions are their texts: Christ and Mohammad are important for what was written down about them.

“That people still want to ban and burn books suggests they retain a remarkable power. Without books we become unmoored from history and what it means to be human. Books invented us. And they continue to reinvent us.”

The 10 Great Books will be discussed at a series of University of Melbourne masterclasses to be held throughout 2017.

10 great books for 2017 - the list

1. The Lost Estate (Le Grand Meaulnes) (1913) by Alain-Fournier Recommended by Professor Peter McPhee, historian and international authority on the French Revolution.

Says Professor McPhee: “Alain-Fournier published the book in 1913. He was killed, aged 27, on the Western Front the next year. A poll of French readers at the turn of this century placed it sixth of all 20th-century books, just behind Proust and Camus. John Fowles called it ‘the greatest novel of adolescence in European literature’. The key theme of the book is the emotional landscape of adolescence: friendship and platonic love; romantic desire and longing; and above all the loss of innocence. It is a captivating and thought-provoking summer read.”

2. The Lucky Country (1964) by Donald Horne Recommended by Professor Glyn Davis, political scientist and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Melbourne.

Says Professor Davis: “The Lucky Country was a wake-up call to Australia in late 1964. It was the first book to look seriously at Australia as an urban nation, not just a pastoral and mining economy. When Horne, a serious and combative journalist, wrote that Australia was ‘a lucky country, run by second-rate people who share its luck’, he started a public debate about national identity which has never flagged. As a book, The Lucky Country has many heirs but none has achieved the sales or impact of Horne’s landmark volume. It remains a key document of Australian civilisation.”

3. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (Wealth of Nations) (1776) by Adam Smith Recommended by Dr Dan Halliday, whose research focuses on the intersection of political philosophy and public policy, such as taxation, education and healthcare.

Says Dr Halliday: “Wealth of Nations gets to the heart of why we should view market society as a morally just way of organising our lives. Smith’s claims are controversial, and must be adjusted in light of the profound economic changes that happened since his day. But Smith still has much to tell us about very recent controversies, such as the rising cost of home ownership, and the dispute about ride sharing and the taxi industry. Times may have changed, but if we want to ask why capitalism is morally defensible, then Smith’s book still gives us answers with which we can start.”

4. On the Origin of Species (1859) by Charles Darwin Recommended by Dr James Bradley, lecturer in the history and philosophy of science.

Says Dr Bradley: “There are few books as important as On the Origin of Species, not just for its description of natural selection, one of the cornerstones of our contemporary understanding of evolution, but because of its philosophical implications. In particular, Origin opened up a cosmos which didn’t necessarily have to be ruled over by an omnipotent deity. What some have called Darwin’s dangerous idea has implications for understanding ourselves and our relationship to the universe.”

Arts & Culture

10 great books to read before you die

5. Silent Spring (1962) by Rachel Carson Recommended by Associate Professor Sara Wills, historian and Associate Dean for Engagement and Advancement in the Faculty of Arts.

Says Associate Professor Wills: “Poignant, powerful, persuasive, this is the environmental text that ‘changed the world’, inspiring the modern environmental movement. Written by a dying women not afraid to take on the might of the chemical industry and powerful vested interests, Silent Spring not only documented the devastating effects of pesticides in clear, compelling language, it spurred a reversal in pesticide policy, led to a nationwide ban on DDT for agricultural uses, and moved David Attenborough to state that it is probably the most influential scientific text ever written after On The Origin of Species. Fittingly, it has been praised as a work that ‘catches the life breath of science on the still glass of poetry’.”

6. Johnno (1975) by David Malouf Recommended by Maxine McKew, writer, board director and Honorary Fellow of the Melbourne Graduate School of Education.

Says Ms McKew: “Malouf’s setting is his home town of Brisbane in the 1940s and the immediate post-war period. Narrator Dante and his friend Johnno dream of escape to Europe, only to find that their elevated expectations are in large part defeated. But at its heart Johnno is an exploration of a complex relationship between two young men – the attraction of opposites, both the thrill and the shame, and ultimately the pain of repression and denial. It’s an absorbing, beautifully rendered book. Read it for its exquisite detail, its sense of place and time, and for Malouf’s poetic take on the loss of youthful promise.”

7. Qur’an (7th century CE) Recommended by Professor Abdullah Saeed, the Sultan of Oman Professor of Arab and Islamic Studies and Director of the National Centre of Excellence for Islamic Studies.

Says Professor Saeed: “The Qur’an is a fascinating book, like any other scripture of a major religion. It is a relatively short text, roughly the size of the New Testament. It is not a book that is easy to read because of its style and the way it is structured and organised. Reading this text requires also a basic understanding of the historical, social, political, intellectual and economic context of the time in which the Qur’an came about. The centrality of this text in today’s discourses on politics, culture and law as well as interreligious relations in Muslim societies is very visible to all of us, and having some understanding of this important text in today’s world is highly desirable.”

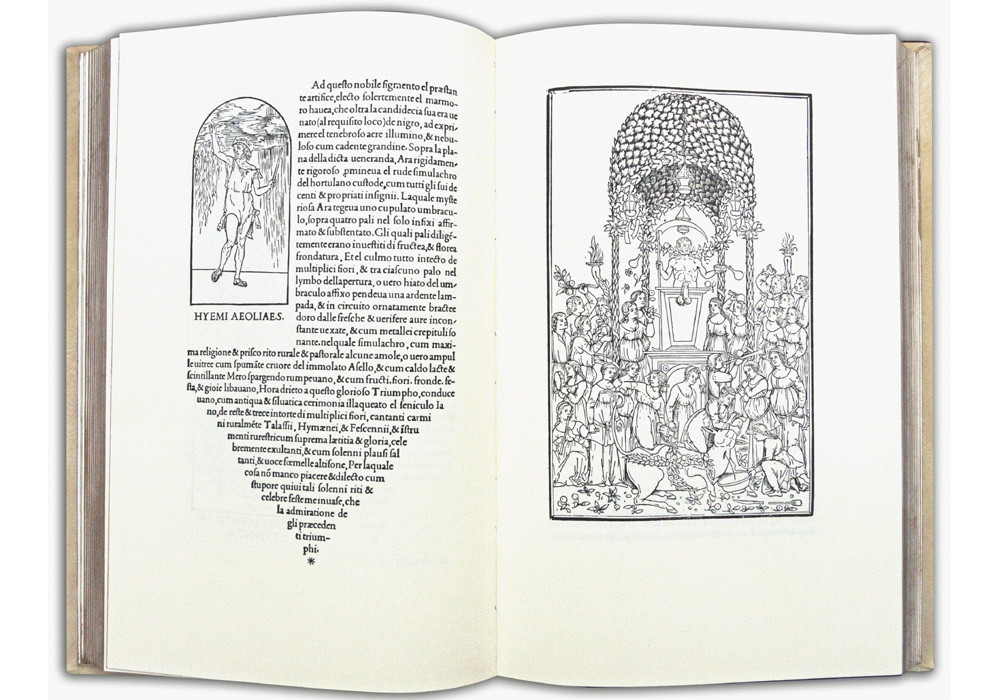

8. Hypnerotomachia Polophili (1499) by Francesco Colonna (?) Recommended by Dr Catherine Kovesi, a historian whose research focuses on early modern Italy.

Says Dr Kovesi: “The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is the only book offered in the 10 Great Books series that, even if you can pronounce its title, you are unlikely ever to have read. Yet it is the most famous book ever printed – as visually appealing in font and illustrations as its text is challenging. Highly enigmatic, with an elusive message, this book takes you into the sophisticated literary and artistic worlds of Italy in the early years of printing.”

9. Medea (431 BC) by Euripides Recommended by Professor Rachel Fensham, Assistant Dean of the Digital Studio in the Faculty of Arts and a dance and theatre studies scholar.

Says Professor Fensham: “Medea is a play for our times. Does it depict the drama of the older wife spurned for a younger, newer woman? Or is it the tragedy of a foreigner seeking recognition in a strange country? What the chorus witness is the macabre revenge of a woman who kills her children in cold blood. As with much ancient Greek drama, this play powerfully addresses questions of justice, gender and civic belonging. And with an emblematic outsider in the title role, productions of Medea also confront the contradictions of a society in flux.”

10. The Leopard (Il Gattopardo) (1958) by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa

Recommended by Professor Mark Considine, Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor of Political Science.

Says Professor Considine: “Regarded as one of the greatest historical novels of its day, The Leopard is the story of a traditional way of life in decline as Garibaldi lands in Sicily and the Bourbon monarchy based in Naples is defeated. A new order of middle classes and dubious characters is thrusting forward and the old Prince and his family face these new realities with regret and with humour. The story is full of disarming personal characters and lyrical episodes of family and traditional life on the great estates and great houses of Sicily.”

Banner Image: Pat Kight/Flickr