Sciences & Technology

Are you a mosquito magnet? Here’s why and what you can do about it

We do need to control disease-carrying mosquitoes in Australia, but more research is needed on GM strains before their proposed release in Queensland

Published 26 February 2025

The British company Oxitec, in partnership with Australia's CSIRO, has announced plans to release genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes in Queensland.

The initiative aims to reduce transmission of the dengue virus, as well as other pathogens spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito by reducing the size of the mosquito population.

The announcement has received significant attention from the public – there's even a petition to the Queensland Parliament to block the release.

While these mosquitoes are unlikely to cause adverse health impacts as some have suggested, there are still legitimate reasons for concern.

Here are three key reasons why we should be wary of releasing GM mosquitoes in Australia.

Only female mosquitoes drink blood to feed their eggs, meaning only female mosquitoes spread disease to humans.

The mosquitoes developed by Oxitec are a Mexican strain of Aedes aegypti, genetically engineered to express a gene that's lethal to females. This means only male mosquitoes can survive and reproduce in the wild.

Sciences & Technology

Are you a mosquito magnet? Here’s why and what you can do about it

Male mosquitoes don’t bite so they can’t spread disease, but they can still mate with wild Australian female mosquitoes and pass on their genes – both the lethal gene and other genes naturally occur in the Mexican strain of Aedes aegypti.

This technique has advantages over similar technologies because it is effective across multiple generations, making the population reduction last longer.

It will also only target Aedes aegypti and won’t affect other mosquito species directly.

The mosquitoes will also carry a fluorescent gene making them easy to identify.

The GM mosquitoes will be sold to businesses and the public, allowing anyone in Queensland to release them on their own property.

They can be raised by adding water to a container and placing it outside. Eventually, male mosquitoes will emerge to mate with the wild population.

The technology is already used overseas with trials showing drastic reductions in mosquito populations, but the situation in Australia is markedly different and so carries different risks.

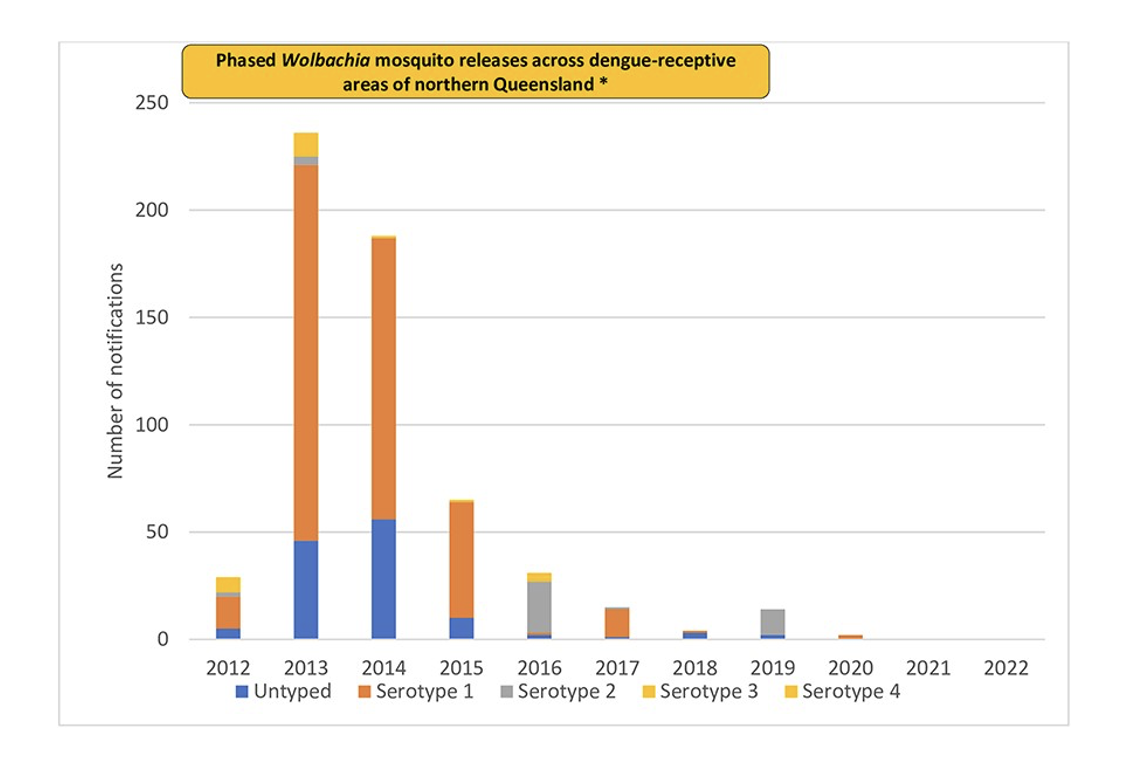

Dengue transmission in Queensland is all but eradicated thanks to a successful control program that has now been running for over a decade.

It involves replacing wild Aedes aegypti populations with ones carrying the Wolbachia bacteria, making them less capable of transmitting dengue.

While imported cases of dengue remain common, it doesn't spread locally because Wolbachia remains at high levels in the mosquito population.

Releasing GM mosquitoes will directly interfere with what is already an effective and ongoing solution to dengue in Queensland.

Unlike Wolbachia, which has little impact on the size of the mosquito population, GM mosquitoes are intended to wipe them out.

This increases the risk that mosquitoes without Wolbachia could establish via accidental introductions (like stowaways) or mosquitoes derived from the GM strain.

Sciences & Technology

Dengue-blocking mosquitoes here to stay

Oxitec has performed rigorous testing to ensure that the genetic modification behaves as expected under a range of conditions.

But they have not tested this in Australia.

Australian populations of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are distinct from those of other countries, including Mexico, where the GM mosquitoes are derived.

For the GM strain to succeed, the introduced gene must be transmitted at a high frequency and kill all female offspring, to achieve a substantial population reduction. While this was the outcome in Brazil, it remains to be seen whether these effects will be the same in Australian mosquitoes.

On top of this, there's been no testing of any interactions between the genetic modification and Wolbachia.

This is an astonishing oversight given that almost all Aedes aegypti in Queensland carry Wolbachia.

While the genetic modification will eventually drop out because any females that remain will no longer carry it, introducing other genetic changes to the Queensland mosquito population is an intended feature of the technology and may be permanent.

The Mexican Aedes aegypti strain will naturally have some different non-GM-introduced genes to the Australian mosquitoes from decades of evolution.

This is a concern because some of these genes could cause undesirable traits like insecticide resistance. Australian populations of Aedes aegypti are unique in their lack of resistance to common insecticides, a trait widespread elsewhere.

Sciences & Technology

We’re not winning the battle between mosquitoes and modern homes

Furthermore, mosquitoes from different parts of the world are adapted to different climates. These differences mean that hybrid mosquitoes could also differ in important ways, with potential consequences for future control efforts.

There have been previous concerns raised about hybrid mosquitoes carrying a different GM strain that caused complete lethality.

While evidence didn't bear these concerns out, the new strain is a different story as it only kills female mosquitoes.

There's a long road ahead before the release of GM mosquitoes in Queensland.

Stringent regulators must first approve the application. The Office of the Gene Technology Regulator is consulting experts and is set to release a risk assessment for public consultation in late March 2025.

Releases will also be subject to approval by the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority.

Even more important is gaining public approval.

There are clear benefits of GM mosquitoes, particularly if the technology is expanded to target other mosquito species or if dengue hotspots appear in future.

But this must be balanced against the risks.

In Queensland, there seems little benefit when we already have an effective solution.

There's still time to address some of the risks raised here. Breeding the genetic modification into Australian mosquitoes prior to any release could help to alleviate concerns about the introduction of foreign genes.

This would allow time for testing to confirm that the intended effects on female lethality also occur in Australian mosquitoes.

This gives us the best chance to eliminate the harmful diseases carried by the Aedes aegypti.