A chance to even the odds

A child’s destiny is heavily influenced by the lottery of socio-economic status and where they happen to grow up, but access to quality early learning can help even the odds for all Australian children

Published 21 May 2019

Each year 60,000 children across Australia start school developmentally behind their peers in key areas like language and emotional competence. These children are in every community, but because of the lottery of where they were born, some children fare worse than others.

But access to quality early learning can help even the odds for all Australian children.

As a way to better understand childhood development and the factors that influence it, the Australian Early Development Census, which began in 2009, is conducted every three years.

Teachers provide an overview of the development of children in their first year of school against five areas that we call domains; physical health and wellbeing, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive skills (school-based), communication skills and general knowledge.

Almost 300,000 or 95 per cent of all children in their first year of school are included in the census.

A tale of four communities

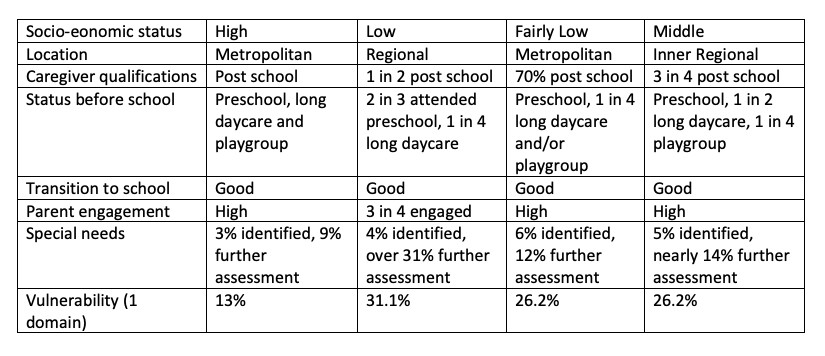

By looking at four Australian communities in detail, we can see stark differences in child development across areas of Australia depending on their socio-economic status and whether they are rural or not.

The differences between the highest socio-economic community in Australia and the lowest are striking (see Table 1).

Children in the lowest socio-economic area are nearly four times more likely to be vulnerable to falling behind in terms of childhood development.

This is defined by a cut-off score based on results of the lowest 10 percent of children surveyed in each of the developmental domains in 2009. Children from low socio-economic areas are accessing early learning at lower rates than children in the highest socio-economic area.

In fact, teachers report up to a third of children have health and development needs that are yet to be diagnosed.

Looking at communities with a fairly low socioeconomic/metropolitan population and middle socioeconomic/inner regional population, we can see differing levels of education participation, but the same level of developmental vulnerability.

Access to opportunities

The data shows that children born closer to cities, in higher socio-economic communities, are less likely to become developmentally vulnerable. While children in higher socio-economic areas are more likely to fare better – the effects of living in rural and remote areas temper this advantage.

Part of the reason for this is access to opportunities – children closer to cities are more likely to attend a combination of learning experiences including preschool, playgroup and early childhood education (which we refer to as long daycare).

This provides a chance to engage children and their caregivers in learning, ultimately, assisting children as they transition to and through school.

For some families, additional support for young children is needed to build their capacity and support the growth of a strong home-learning environment; this is an environment in which parents or carers support the development of children through activities like talking, singing and rhyming, looking at books and imaginary play with toys, as well as a variety of physical and social activities.

This can also help identify any need for further assessment.

A high number of children have undiagnosed needs such as emotional problems, language disorders and behavioural issues that are likely to make learning more challenging if left unaddressed – the percentage of children requiring assessment is startlingly high in some rural and remote communities.

A stronger start to school

Early intervention is vital for children with special needs, but nearly 40,000 children have not had an early diagnosis and need further assessment in their first year of school.

Many of these issues could have been identified during the child’s first five years, giving them a stronger position to start school. These issues can be addressed through our universal platforms – like maternal and child health and early childhood education and care.

Studies, such as Right@Home, show it is possible to positively influence the home-learning environment and identify children who may require additional support in key areas like language and communication.

Quality early-childhood education plays a strong role in helping to identify and address emerging issues for children before they even start school, linking children and carers to the support services they need.

There is an urgent need for the government to address inequity faced by children and their families – it’s not fair that a child’s destiny is so heavily influenced by the lottery of socio-economic status and where they happen to grow up.

Banner: Getty Images