A chance to unwrap the mystery around mummies

In the museum world, ancient Egypt is a perennial crowd pleaser, but the display of human remains - even those that are several thousand years old - requires careful thought

Published 26 October 2015

As far as crowd-pleasers go, it’s hard to beat mummies.

When Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs opened at the Melbourne Museum in 2011, it broke all previous records for touring exhibitions in Australia, attracting more than 800,000 visitors over its run and 10,192 visitors on a single day in May.

Yet the popularity of Egyptian mummies belies the fact that displaying human remains can be highly controversial, with ongoing ethical debates around their display.

Last month, a new exhibition titled Mummymania opened at the Ian Potter Museum of Art in Melbourne. Featuring traditional Egyptian funerary objects such as amulets, figurines, offering vessels, bandages, and a decorated coffin, the exhibition also features mummified human remains.

As such, it offers an opportunity to reconsider how museum spaces exhibit and facilitate respectful engagement with the dead.

It also offers a chance to reflect on the more recent history of the mummy – its role in scientific investigations into ancient disease and medicine, and its place in popular culture.

Recent history of the mummy

Since the 1970s, indigenous groups have rightfully claimed the return of ancestral human remains held in museum collections.

Ancient Egyptian mummies have no living claimants, however, and are part of a long tradition of unearthing and display that forms part of the history of archaeology and the ongoing public fascination with ancient Egypt.

Interest in Egyptian mummies by Europeans can be traced back to the 5th Century BC and the Greek historian Herodotus who provided one of the first accounts of the mummification process.

Throughout the following centuries mummies were plundered for jewellery and amulets; ground up and used as medicines; and even as a pigment base for paint.

The dark resinous coating applied to mummies as part of the embalming process was mistakenly believed to be bitumen (Persian “mummia”) which was used as a medicine in Greece and the Near East.

Egyptian mummies were harvested for the dried resin as well as for their dried flesh. By the 16th century mummy had become a highly-prized drug exported to Western Europe where it was ground up, applied to wounds, and swallowed.

As well as being used as medicine, by the 18th Century Egyptian mummies had become the focus of the medical community as scientific specimens. Mummies were dissected by doctors at private homes in front of audiences of medical practitioners and curious spectators.

Fragments of the mummy’s flesh, bandages, and accompanying artefacts were passed among the audience to be touched, smelt and tasted.

During the 19th century mummy unwrapping events moved to more professional locations such as medical and military museums, hospital operating theatres, laboratories, pharmacies, and respected scientific organisations such as the Royal Institution.

These popular, spectacular events attracted a paying audience made up of academics and the interested public. Melbourne had its own mummy unwrapping in 1893 when a female mummy was unwrapped in the concert hall in the Royal Exhibition Building in front of a crowd of 700 people, mostly women.

Popular culture & the mummy

Egyptian mummies were also used in art; pulverised mummies formed the basis of Caput Mortuum, also known as Mummy Brown, a rich brown pigment used in paintings from the 16th up until the 20th century. Mummy Brown featured in paintings by artists such as Eugène Delacroix and Edward Burne-Jones among others.

When Burne-Jones discovered the pigment really did contain ground-up mummy, he ceremoniously buried his tube of paint in the garden. Despite its widespread use, Mummy Brown eventually fell out of favour through a combination of distaste regarding its origins and technical problems such as its tendency to crack.

The mummy even featured in 19th-century fiction where it was portrayed as a gentle, even romantic character up until the publication in 1892 of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story Lot No 249.

In this story a mummy is brought back to life by an Oxford college student through the use of ancient Egyptian magic and sent to attack all the people the student has a grudge against.

The story marked a turning point in the representation of the mummy who from that time on would be depicted as a frightening reanimated corpse.

By the 20th century ancient Egyptian mummies were definite villains, sinister, predatory figures featuring in pulp magazines dedicated to fantasy, science fiction, mystery and the occult, as well as in film.

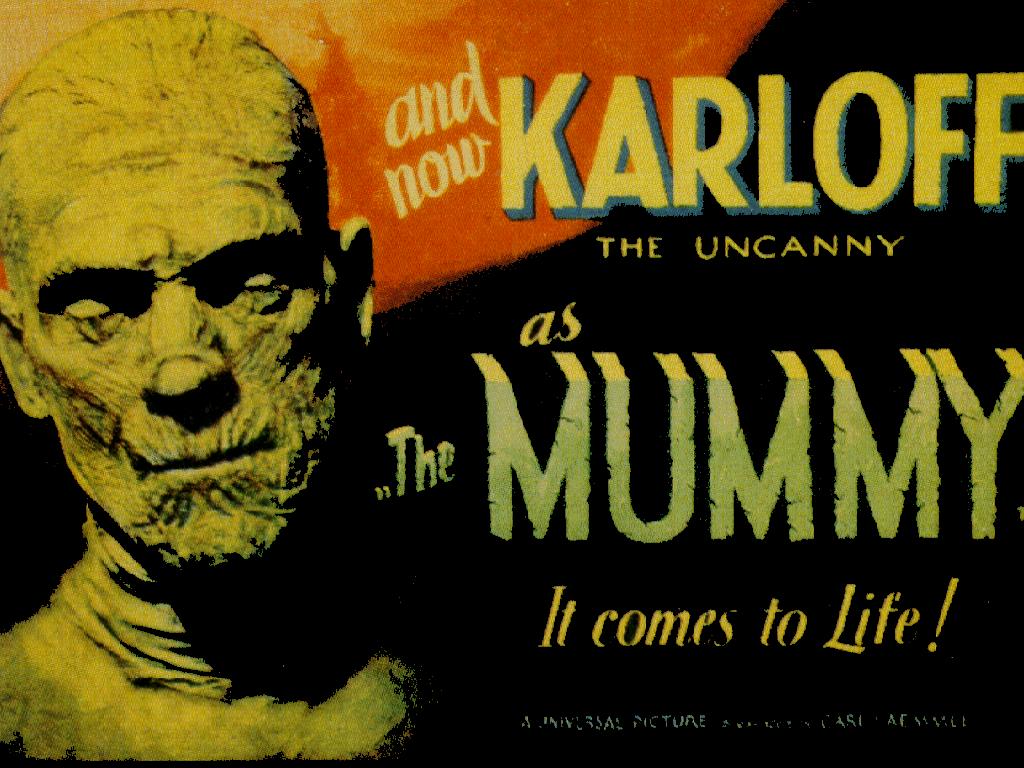

Universal Studio’s The Mummy (1932) starring Boris Karloff, is the classic mummy horror movie. In this film Imhotep, an Egyptian priest who had been buried alive for attempting to resurrect his beloved princess, is accidentally revived when an archaeologist reads from the life-giving Scroll of Thoth. The mummy then stalks a beautiful young woman he believes is his lost love reincarnated.

Archaeologists excavating an Egyptian tomb are terrorised by a mummy in The Mummy’s Hand (1940), and in a sequel, The Mummy’s Tomb (1942), the mummy reappears at the archaeologists’ home in New England. More recently Universal made The Mummy (1999), followed by The Mummy Returns (2001), both of which are based on the original premise of the 1932 movie.

But, of course, mummies are not fictional movie creations. They’re real, and still very much with us, as exhibitions such as the current one remind us.

Mummymania, at the Ian Potter Museum of Art, runs until April 17, 2016. Details here.

This article was first published in The Conversation.