Arts & Culture

No bandwidth to think is the cost of being time poor

A four-day work week means people get more done in less time, and that could help boost Australia’s stagnating productivity

Published 22 July 2025

Productivity is top of mind for Australia’s Albanese government. Treasurer Jim Chalmers is convening a productivity roundtable, bringing together union and business groups, and seeking public submissions “to unlock new ideas and build consensus around reforms”.

Concerns about productivity are not new: Australia faces declining productivity growth, which risks affecting our national prosperity – that is, how well-off you and I are.

But the Productivity Commission says we have a ‘productivity predicament’: productivity growth is not just slowing – in 2023 and 2024, it stopped.

In terms of the big picture, that means incomes will be lower and working time will be longer.

But here’s an idea. Counter-intuitive it may be, but rather than demanding longer working hours from workers to achieve the same economic outputs, what if our employers and politicians started to realise that the four-day week could itself boost productivity?

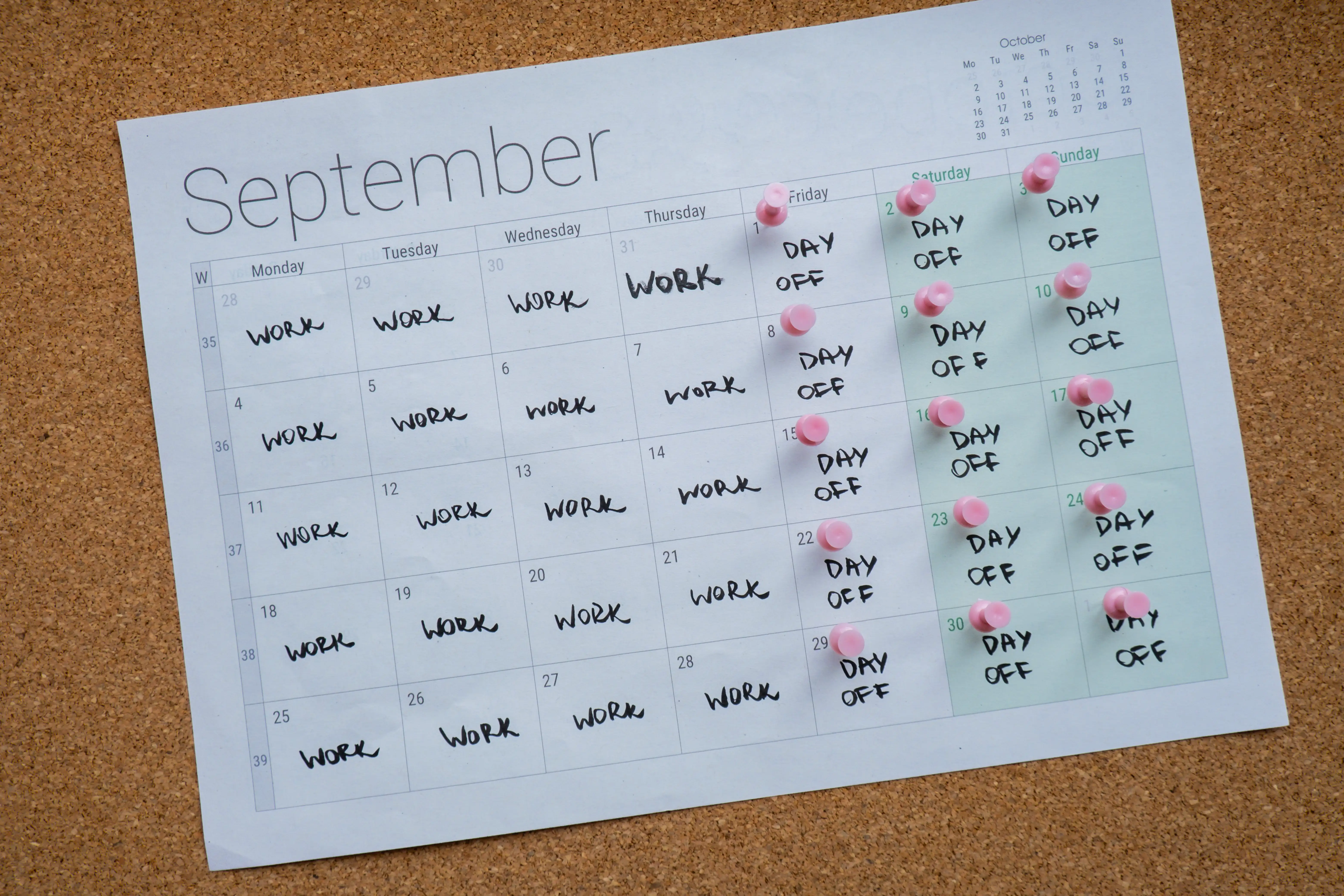

The four-day week involves workers keeping the same level of pay, while working only four days (or 30 to 32 hours) per week.

This would be considered full-time, as they would still be doing the same amount of work.

Arts & Culture

No bandwidth to think is the cost of being time poor

The non-profit 4 Day Week Global sees this as a 100-80-100 model – 100 per cent of the pay, 80 per cent of the time, but 100 per cent of the productivity.

Trials of the four-day work week have so far shows it works. During testing in Australia, the UK, Japan and Germany, both staff and managers found that at worst, productivity was maintained, and in many cases, it actually improved.

These trials seem to indicate that shorter working hours can actually boost productivity.

So, what’s going on?

Short, focused hours of work can be better for getting things done than working longer hours. Inadequate rest and not enough down-time away from work can lead to poor health and reduce our engagement with work.

Four-day work weeks also refocus our attention on what it means to be ‘productive’. During the trials, employees reported being more strategic and selective with their time management.

Emails and meetings were two things that were typically reduced or even eliminated.

Adopting a four-day work week means people get more done in less time and shift their work behaviours to become more efficient and productive.

Those workers involved in the trials also reported feeling less stress, burnout and fatigue, and reported better work-life balance, getting more exercise and more sleep.

So, what’s the downside?

Business & Economics

Breaking the workplace code of silence

Well, because it involves completing the same amount of work in less time, it might mean some work intensification. This might not be appropriate for people with health issues or disabilities; in theory, other workers might also find it more stressful.

But in the trials so far, while some people reported working harder, this seemed to be offset by having an extra day off work.

So, while we might work harder, we then have more time to recover and do other things.

We also cannot do our jobs exactly the same way in a four-day week (which is why emails and meetings are on the chopping block).

Successfully adopting a four-day week requires workers and bosses to have frank conversations about what tasks are adding value and get rid of what are not.

Australian government inquiries have already recommended adopting or trialling a four-day work week. In 2023, this included in the Australian Capital Territory and, at the federal level, by the Senate Select Committee on Work and Care.

Australian companies like Unilever, Medibank and Oxfam are conducting – and often extending – their own trials of a four-day week.

In 2025, the Greens announced a four-day work week election policy. The President of the Australian Council of Trade Unions, Michele O’Neil, has also expressed support for the change.

So far, the evidence in favour is strong.

Trials across countries and different industries have consistently reported benefits.

A four-day work week may boost productivity, encouraging workers and organisations to refocus their attention on what it means to be productive, and become more strategic and selective with their time management.

Politics & Society

‘Forcing’ workers into the office misses the point

The promise of reduced working time, without a cut in pay, offers employees incentives to identify and act on productivity gains beyond what might be achieved in regular working arrangements.

It would also mean that the benefits of increased productivity are shared in a way that is much fairer.

These increases would allow workers to have more time off work, rather than just going into higher profits for shareholders and pay for executives.

While individual employers and employees can negotiate a reduced working week (as has been done at Oxfam), there is also a role for government to reconsider and amend maximum working hours in Australia.

So, help save the Australian economy and negotiate to take Friday off.