Business & Economics

The COVID-19 responsibility we all own

Can the challenges we face during the coronavirus pandemic help us reconsider what matters most and how we live our lives?

Published 5 May 2020

The challenges we are all facing as a result of the coronavirus pandemic have the potential to cause serious and sometimes long-lasting problems for individuals and societies.

But can they also spur us to reconsider who we are, what we value and how we live our lives?

The coronavirus context has challenged many of the assumptions on which our day-to-day lives are based – the way in which we engage with others, our capacity to travel where and when we want to, and how we go about our schooling and work.

Indeed, for many, it has brought the loss of work.

All this has been intermingled with uncertainties around the threat of coronavirus infection. It is an unseen or invisible threat, potentially carried by the people around us who usually represent safety and support during stressful events and disasters.

Business & Economics

The COVID-19 responsibility we all own

In some ways, this extended period of threat from the coronavirus has similarities to traumatic events and natural disasters, like Australia’s recent bushfires and drought.

All of these events challenge our perceptions of the world in which we live as being predictable and controllable.

Similarly, it isn’t only the fears and exposure to the threat itself that pose a risk to our physical and mental health. The consequent flow-on effects of additional stressors may also take a toll.

This impact of additional stressors is clear from international and Australian research following trauma and disaster, most particularly the Beyond Bushfires study examining the long-term impacts of the Black Saturday bushfires.

In the case of the coronavirus pandemic, these additional stressors include self-isolation and the significant impact on employment and financial stability.

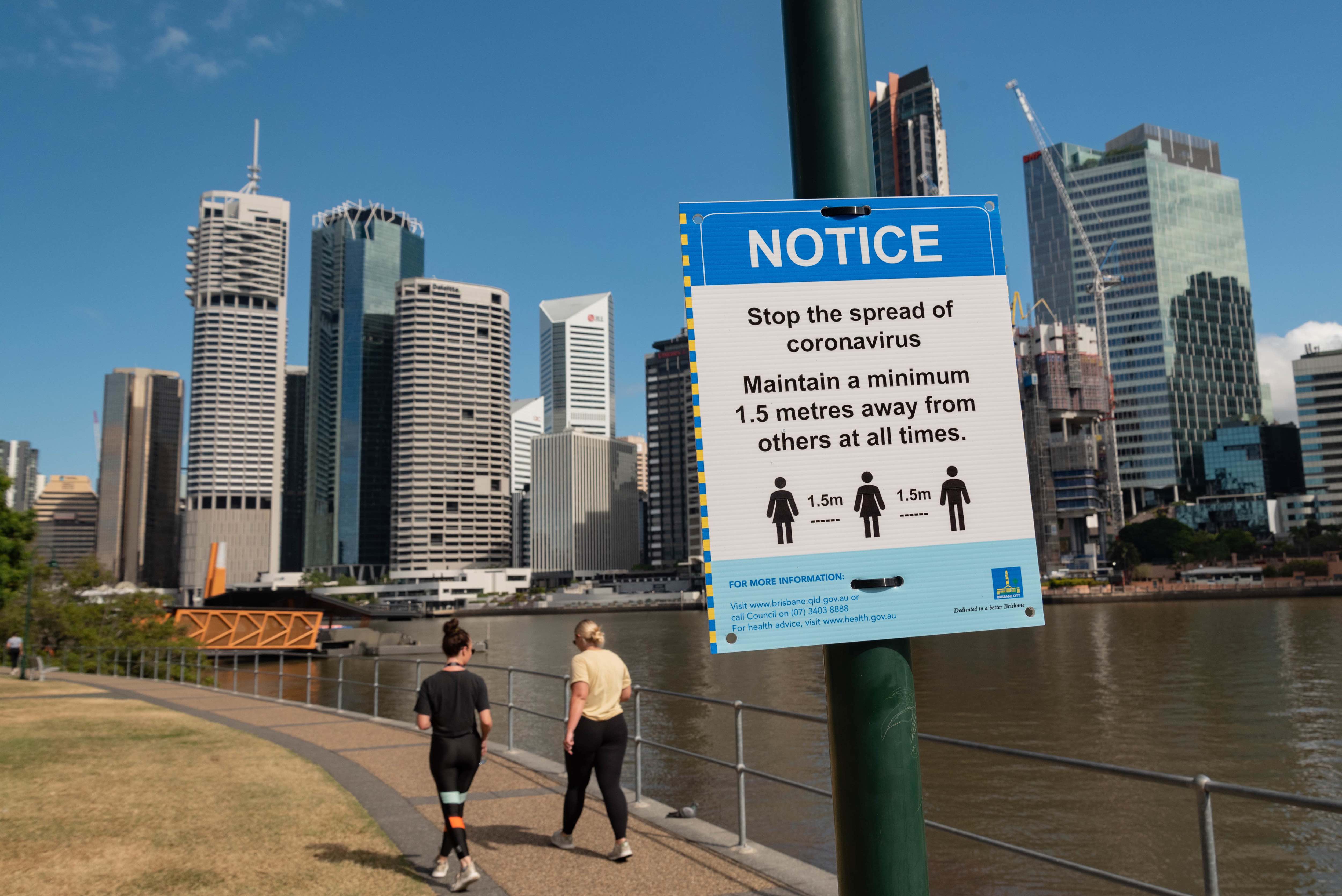

In Australia, we appear to be making terrific headway in terms of containing the spread of the virus. While there is definitely no room for complacency, we are seeing the benefit of the restrictions and social distancing implemented across the country.

But the stresses of isolation and employment instability carry their own risks for further difficulties. Self-isolation is associated with social disconnection, loneliness, depression, and the risk of increased alcohol and drug use. These psychosocial impacts can continue for many years.

Health & Medicine

Australia’s COVID-19 relationship with booze

As observed through research studies across 63 countries following the Global Financial Crisis, the impacts of unemployment and financial stress include anxiety, depression and risks around suicidal behaviours.

This combination of mental health vulnerability, alcohol and drug misuse, anger and financial stress also create a heightened risk of family violence.

These are all risks we need to be highly alert to and try to mitigate.

Indeed, we have seen considerable federal and state government initiatives, supported by the National Mental Health Commission, to recognise and target these issues.

However, as research into the effects of trauma and disaster shows us, the coronavirus environment also offers the opportunity for development, change and transformation at individual, familial, community and societal levels.

What happens when we are forced to slow down and when our assumptions about how we live our lives across familial, social, occupational and material dimensions get challenged?

Over the past 20 years, there has been increasing interest in a concept called posttraumatic growth – how we find ways to discover ourselves anew following seismic moments.

Potentially, we develop a deeper understanding of ourselves, come to see the world around us differently and experience an enhanced awareness and appreciation of the people around us.

Health & Medicine

What is COVID-19 doing to our mental health?

We have more time to notice the moments of life, rather than seeing and experiencing life in a blur of weeks, months and years.

Research shows that survivors of trauma and disaster often describe positive changes that sit alongside the pain and distress of the trauma – these are often referred to as posttraumatic growth or posttraumatic transformation.

Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, we have seen changes in our community reactions.

We have moved from initial confusion to some degree of social fragmentation, demonstrated by the hoarding of toilet paper, averted gazes when passing people in the street and occasional overt acts of racism.

Yet, as individuals and as a community, we have still recognised that, inherently, we are all connected.

We have seen people reach out to neighbours, safeguard their elders, identify and help those in need, support friends and work colleagues and, perhaps fundamentally, take the opportunity to deepen the quality of time with their families.

This time that we are all currently living in gives us a powerful opportunity.

When our assumptions of how life unfolds are challenged, we are in a position to consider anew what we value, how we live and who we are.

Banner: Getty Images