Politics & Society

How did it come to this?

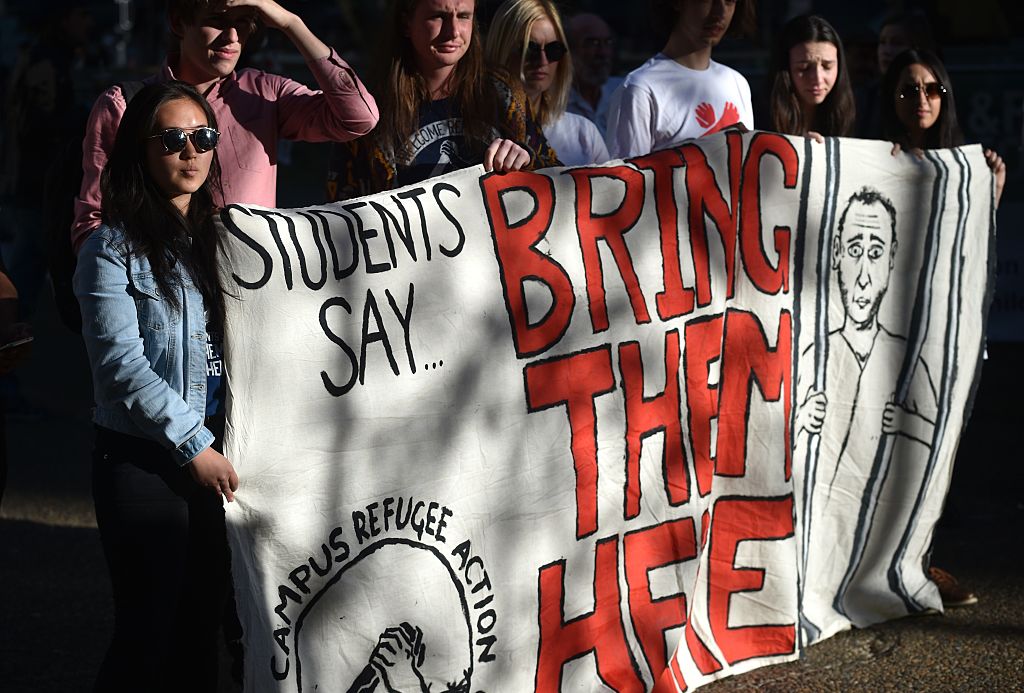

Researchers from universities around Australia are adding their voices to the groundswell of concern about the country’s treatment of refugees and asylum seekers, demanding #nomoreharm

Published 16 October 2018

Australia’s policy of detaining refuges and asylum seekers in offshore facilities is tarnishing our reputation internationally and, more worryingly, harming people and creating intractable new problems, argue some of the country’s leading academics.

As the UNHCR and Médecins Sans Frontières Australia condemn Australia’s warehousing of refugees on Nauru and Papua New Guinea, legal experts are arguing the detention regime may constitute a crime against humanity.

The Australian Government was also recently reported to the Human Rights Council by the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention for being in breach of UN guidelines on arbitrary detention.

And now academics from Australian universities are adding their voices to this groundswell of concern, coming together for a National Day of Action on October 17.

Politics & Society

How did it come to this?

So what do they hope to achieve?

“This is not simply an academic protest: there is a strong groundswell of public opinion which is contesting government policy on immigration detention and offshore processing,” says Professor Philomena Murray, National Co-Convener of Academics for Refugees and Lead Investigator on a $500,000 comparative research project examining the impact of externalisation policies on refugee protection in Australia and Europe.

“As academics we are in a unique position of having knowledge, research findings and expertise to illustrate the need for an alternative approach. We can also access national and international networks to examine options that do not feature detention, closed borders and racist immigration systems.

“Our research can change minds and change policy, and that is what we seek.”

Professor Murray says academics can work together with students, university staff and the broader community to voice clear and informed opposition to “the shirking of responsibility and ignoring of clear evidence by major parties”.

Pursuit spoke with Professor Murray and some of her University of Melbourne colleagues taking part in the Day of Action, to understand why they are raising their voices in protest.

Professor Philomena Murray, Dr Claire Loughnan and Dr Jordana Silverstein

Health & Medicine

Young and resilient

When it comes to the treatment of refugees and asylum seekers, there is a cruel bipartisanship in Australia today.

We need to reframe policy towards justice, human rights, health and international responsibilities, and away from prolonged suffering and closed borders.

Researchers are concerned that the framework of deterrence, which underpins Australia’s detention policy, doesn’t ‘save lives’, nor does it deal with the underlying reasons why people seek refuge.

Deterrence has seriously undermined efforts to improve the global humanitarian situation: it has created grave and increasingly intractable new problems and acts of violence. We believe that the support for the end to offshore detention among the community must be acted on by both parties.

What is particularly concerning is that the unacceptable practice of detention has somehow become something to admire for some Western leaders, as Australia’s offshore processing and immigration detention regime has become a model for border security policies in other countries like the US.

We need something different: a transformation in how states understand and respond to the movement of people around the world. This requires humane, compassionate leadership and courage.

Professor Louise Newman

We’re currently seeing a mental health crisis among detainees on Nauru.

Politics & Society

Australia’s place at the human rights table

Typically, people being held in offshore detention are very vulnerable to begin with – they have almost all fled a very dangerous situation, and have often experienced a traumatic journey. Then they find themselves in a system that denies their basic rights, including their legal rights, and does not protect their children.

We’re seeing an increase in self-harming behaviours, depression, anxiety, severe withdrawal, or even in some cases, resignation syndrome - a profoundly dangerous condition where children go from being depressed and withdrawn, to mute, to ultimately losing consciousness.

We’re seeing so many cases of resignation syndrome on Nauru mainly because of the very deprived environments there. It seems to happen in particular when hope is taken away and children lose any sense of power - withdrawing is the one thing they can do. It is extreme and dangerous, and can be life threatening.

Every case of resignation syndrome so far has required us to go to court to have the patient evacuated from Nauru, and this is where the politics directly impacts people’s health. Australia’s continued blind adherence to damaging policies means we are now being held up in a negative light internationally.

I’m also particularly worried about babies being born on Nauru right now, because we’re seeing rising incidents of postpartum psychosis - an extreme form of post-natal depression.

This is dangerous for both mothers and babies; very young babies are showing signs of distress and they are not developing appropriately. These children are highly likely to show signs of behavioural and emotional problems by the time they become toddlers and pre-schoolers.

Politics & Society

No country, no rights, no hope

Professor John Tobin

Australia’s international human rights obligations are clear.

We can’t detain refugees or separate refugee families unlawfully or arbitrarily; nor can we treat them inhumanely. Importantly these obligations don’t just extend to the treatment of refugees within Australia’s territory, but to all within our jurisdiction.

Put simply, this means that if Australia exercises ‘effective control’ over the way refugees are treated in offshore processing centres, then we owe obligations to them under international human rights law. So what amounts to ‘effective control’?

Considering the funding arrangements and control Australia exerts over the operation of the centres on Nauru and Christmas Island, there is a strong argument that we have effective control of offshore processing centres.

The problem, however, is that there is no coercive mechanism to hold Australia accountable for any violation of its human rights obligations.

Refugees can lodge complaints with United Nations bodies like the Human Rights Committee and various Special Rapporteurs. And while these complaints play an important role in clarifying Australia’s responsibilities and draw international attention to violations of international law, their decisions aren’t enforceable.

What Australia requires is for our political leaders to show courage and leadership; if ordinary Australians keep demanding that politicians of all persuasions respect the rights of refugees and provide them with a ‘fair go’, we might start to see some real change.

Banner image: Getty Images