Business & Economics

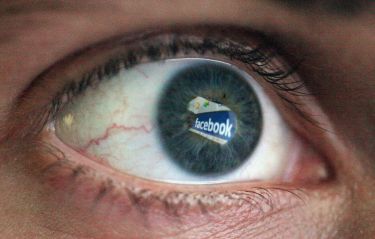

Taking on big tech: Where does Australia stand?

While there are no quick fixes, the ACCC’s final report into digital platforms in Australia finds that powerful tech giants like Google and Facebook warrant close competition scrutiny

Published 29 July 2019

The final report of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) on its Digital Platforms Inquiry was released by the government late last week.

The Inquiry concerned “the effect that digital search engines, social media platforms and other digital content aggregation platforms have on competition in media and advertising services markets.”

Central to the ACCC’s inquiry were the questions: Do Google and Facebook hold substantial power in crucial digital markets and does this pose a risk to competitive processes?

In its final report released by the government, the ACCC correctly answered both questions with a resounding “yes”.

The ACCC did not set out to determine whether either company had broken the competition rules. That can only be determined in an investigation of specific conduct based on specific facts and evidence.

Business & Economics

Taking on big tech: Where does Australia stand?

There is at least one such investigation under way and signs are that more will follow.

Having identified competitive risks, the ACCC did set out to determine how they might be contained. Its proposals are rightly cautious, reflecting the complexities of digital markets and the challenges in ensuring that any intervention protects the competitive process rather than individual competitors.

As the ACCC points out, substantial power won by serving consumer interests is not against the law and, it acknowledges, Google and Facebook provide services that are highly valued by their users.

The report highlights distinctive features of digital markets and platform business models that contribute to the power of these companies: extraordinary economies of scale, network effects, economies of scope, massive accumulations of data and the use of highly sophisticated data analytic techniques.

It is important to recognise that these features also reflect efficiencies that deliver value for consumers.

However, whenever markets are highly concentrated, there are risks that the incumbents will be tempted to serve largely their own interests – raising prices, reducing quality and narrowing choice for consumers.

There are also risks that they will use their power to prevent new entrants from offering a better deal and disadvantage other businesses dependent on the incumbent’s services to serve consumers in their own markets.

Politics & Society

Keeping tabs on the tech giants

The ACCC found that these risks abound in markets dominated by the incumbents: general search and search advertising services in the case of Google, and social network and display advertising services in the case of Facebook.

Despite the tech companies’ contentions that they compete in broader markets, the conclusions by the ACCC are consistent with approaches adopted internationally.

What does the ACCC propose be done to reduce the risks? There are no quick fixes or magic bullet solutions.

The ACCC rightly rejected the idea that the major platforms should be broken up. Given the highly interconnected complex nature of markets in which the major platforms participate, divestiture would not guarantee and may, in fact, harm consumer welfare.

Cognisant of that complexity, the report’s recommendations show the ACCC’s commitment to build its capacity to aggressively enforce the competition rules in relation to digital platforms and actively review acquisitions that would entrench market power further.

These are long-term, challenging projects but are crucial to protecting competitive processes.

The majority of the report’s recommendations relate to regulation and other reforms to redress imbalances in information and bargaining power between the platforms and business users, and between the platforms and consumers in connection with the collection and use of personal data.

Politics & Society

White supremacist terrorism, technology and the law

These initiatives also present challenges, not least to ensure they don’t accentuate risks to competition.

The ACCC proposes establishment of a new specialist branch to build and sustain the human and intellectual capital necessary to continue studying digital platforms and enforcing the competition and consumer rules in their markets.

This is a welcome initiative. It replicates similar capacity-building initiatives in the US and Europe.

The report is peppered with references to European cases in which Google has been subject to thundering fines for various abuses of dominance.

It also invokes the European mantra that powerful companies have “special responsibility”.

But the Australian misuse of market power prohibition does not mirror its European counterpart. The European law is wider and more flexible than ours.

Some types of unfair or exploitative conduct may be an abuse of dominance in Europe. We have different laws for such conduct, including prohibitions on unfair contract terms and unconscionability.

Business & Economics

Why data is king

The ACCC has proposed that these aspects of the Australian Consumer Law are strengthened and possibly expanded. Reforms like this would not apply to digital platforms only and are part of a larger project that has been under discussion for some time.

The recently amended section 46 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 is yet to be taken for a proper run and, in the digital context, its application will be complicated by the rapid pace of innovation and the fact that competition is more often ‘for’ than ‘in’ the market.

There is a recommendation to amend merger laws to refer to potential competitors and data assets. This is a useful start in ensuring that the law reflects particular features of digital mergers.

It is also proposed that Google and Facebook voluntarily notify the ACCC of any future acquisition. This is a polite request backed by a thinly veiled threat of repercussions for failure to accede.

However, the report also implies that neither of these proposals are likely to be enough.

Further changes to the merger law may be necessary to persuade judges that we need to stem unhealthy concentration levels in the Australian economy generally. It is also nigh time that we have a compulsory notification regime, triggered by a combination of turnover and transaction value thresholds to ensure nascent competitors are not snuffed out.

Business & Economics

Putting the “E” into e-consumer protection

Both of these are bigger conversations that the ACCC needs to engage the government and other stakeholders on.

Reference to the Consumer Data Right as a measure to strengthen competition, facilitate switching and spur new entry was an omission from the preliminary report.

The final report corrects the omission but, as the ACCC points out, the case for data portability (or interoperability) in relation to the big platforms is weaker than in relation to big banks and big energy companies.

It has placed these potential reforms on its “possibly in the future” list.

The Commission has stepped away from its preliminary proposal that there be a regulator to monitor and oversee commercial relationships between platforms and their significant business users, advertisers and media organisations.

Bargaining imbalances should only be regulated where there is good evidence that markets are failing, and more transparency and certainty is required to protect incentives to invest and innovate.

The ACCC was not persuaded that the grievances of advertisers and news organisations constitute market failures warranting the invasive regulation that appeared to be contemplated – at least not yet.

It may also have listened to criticism that the proposed regulation could benefit traditional players in disrupted industries more than it benefits consumers.

Sciences & Technology

Data privacy and power

The advertising industry is highly fragmented, complex and constantly changing. The evidence that opacity, verification and discrimination is distorting competition was questionable at best.

In light of this, the proposal that the ACCC conduct a thorough examination of dynamics in the ad tech supply chain before making any firm recommendation for intervention is commendable.

For the media industry, the compromise is that each platform be required to negotiate a code of conduct to be overseen and enforced by the Australian Communications and Media Authority.

Whether this addresses media concerns about notice of algorithmic changes, value appropriation and original content will depend substantially on ACMA’s skill and resources.

Recognising that the platforms are knee-deep in the media business, the call for a wholesale overhaul of media regulation to level the playing field and remove regulatory impediments to competition is a no-brainer.

This appears to have been accepted by the government.

The need for broad ranging reform of our privacy laws to wrench them into the digital age is also unlikely to be controversial.

The platforms may grumble at the proposal that there should be additional privacy requirements for them and the anticipated complaint about the lack of an international standard for such requirements has merit.

Sciences & Technology

Human dignity and digital identity

But the proposed development of an enforceable code of conduct at least allows them a seat at the negotiating table and the opportunity to ensure that the regulation is workable.

Aside from the consumer protection dimension of the proposed reform, the ACCC is correct that giving consumers more control of their data could open the way for more competition on privacy. It should also enhance the consumer trust critical to the digital economy.

However, from a competition perspective, a pressing challenge in the privacy reform process will be ensuring that onerous regulatory burdens don’t disproportionately affect small businesses and prospective entrants.

The ACCC is right to suggest it be involved in the process to prevent such a risk from materialising.

The ACCC’s important work on digital platforms has just begun and there is a long and bumpy road ahead.

The government should give it the time and money it will need to get on with it.

Caron Beaton-Wells is host of the Competition Lore podcast, exploring competition policy and law in a digital age.

A version of this article also appears on The Conversation.

Banner: Minister for Communications Paul Fletcher speaks to the media following the release of the ACCC’s report on its Digital Platform Inquiry/AAP