Sciences & Technology

Using engineering to (em)power others

A model of Mount Vesuvius erupting, designed in 1775, has been rebuilt by engineering students for a new exhibition at the University of Melbourne

Published 30 July 2025

Not many students can say they’ve completed a project that was set 250 years ago.

Inspired by a design originally developed in 1775, engineering students Yuji (Andy) Zeng and Xinyu (Jasmine) Xu have built a multimedia installation of Mount Vesuvius erupting.

Exactly 250 years later, it is now coming to life using modern LED lighting and electronic control systems, built in the student workshops in The Creator Space at the University of Melbourne.

Master of Mechanical Engineering student Yuji tested and built a lighting mechanism to imitate lava flow, while Master of Mechatronics student Xinyu developed the interactive controls.

Research engineer Andrew Kogios and I oversaw the project, which was inspired by the University’s Grand Tour Exhibition. The collection brings together depictions of travelling in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The original 1775 mechanism was designed by Sir William Hamilton, British ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily from 1765 to 1800.

Mount Vesuvius entered an active phase shortly after Hamilton’s arrival in Naples, and Hamilton frequently climbed up the volcano to observe its activity within the crater and the lava flows down its sides.

Sciences & Technology

Using engineering to (em)power others

While most infamous for destroying the towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum in 79 A.D., Mount Vesuvius also experienced a major eruption in 1631 that killed thousands.

When Hamilton first arrived in Naples, Vesuvius was simply belching smoke, and Hamilton would climb the mountain to peer down into the crater and collect lava samples.

But on an excursion up the mountain in 1766 Hamilton came to appreciate the risks. He wrote:

“I heard a violent report, and saw a column of black smoke followed by a reddish flame, shoot up with violence from the mouth of the volcano, and presently fell a shower of stones, one of which falling near me, made me retire with some precipitation, and also rendered me more cautious of approaching too near, in subsequent journeys to Vesuvius.”

Curiosity often overwhelmed caution. Four months later, Hamilton heard a major explosion and instantly rushed from Naples:

“I passed the whole night upon the mountain… the lava had the appearance of a river of red hot and liquid metal, on which were large floating cinders half lighted, and rolling over one another with great precipitation down the side of the mountain, forming a most beautiful and uncommon cascade.”

A keen naturalist and antiquarian, Hamilton began sending detailed reports back to the Royal Society of London, where they were read at the society’s meetings and published in its Philosophical Transactions.

His reports were accompanied by samples of the different types of lava, sulphur and cinders, both to illustrate his accounts and for chemical analysis.

As he widened his exploration of southern Italy, including the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum, he realised that here was evidence of a landscape shaped by one of Nature’s great forces.

Despite producing extensive reports and collecting lava samples, Hamilton wanted to convey the visual power and sublimity of Vesuvius erupting to people in England.

He commissioned British-Italian artist Pietro Fabris to paint the dramatic eruption and lava cascades of 1767.

Fabris painted the scene onto transparent fabric, which Hamilton sent to the British Museum with instructions on how to light the image from the rear to create a dramatic night-time effect.

Sir John Pringle, council member of the Royal Society, reported to Hamilton the impact of the painting on viewers:

“The representation of that grand and terrible scene, by means of the transparent colours, was so lively and so striking, that there seemed to be nothing wanting in us distant spectators but the fright that everybody must have been fired with who were near.”

The appetite for Vesuvius in Britain, especially in London, was fired by Hamilton’s accounts of the eruptions during the 1600s and 1700s.

The English actor and producer David Garrick introduced scenes of Vesuvius erupting in his production of The Witches at Drury Lane Theatre in 1771.

Meanwhile, London’s pleasure gardens – familiar to Bridgerton fans – would often conclude their night-time events with a fireworks show, themed as volcanic eruptions.

Hamilton also experimented with designing an animated version of the backlit transparency of Vesuvius that he had sent to the British Museum. It is unclear if the apparatus was built at the time.

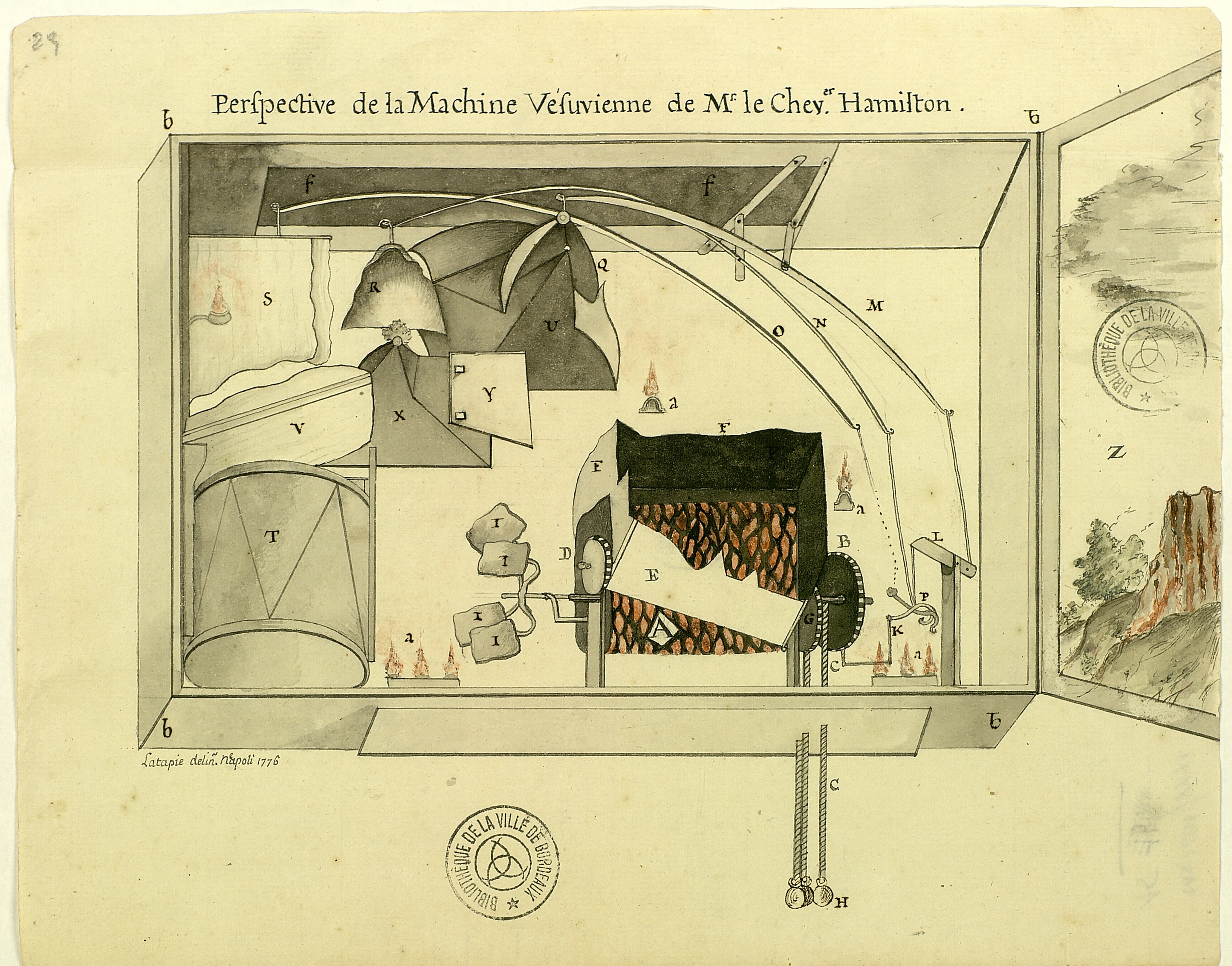

But a detailed sketch of Hamilton’s Vesuvian apparatus has survived in the Bibliothèque municipale de Bordeaux.

The apparatus was designed to animate Pietro Fabris’s watercolour, Sir William Hamilton conducting their Sicilian majesties to see the current of lava from Vesuvius in May 1771, night view of a current of lava.

The view showed a cascade of lava falling into a valley, with Hamilton depicted in the foreground showing the dramatic sight to the King and Queen of Naples. Fabris includes himself lower left, sketching the scene in preparation for his detailed painting.

Hamilton’s apparatus used a clockwork drive to rotate a perforated drum that would filter moving candlelight onto the lava cascade; an additional mechanism lifted vanes to reveal lava flow higher up the volcano, while the mechanism could also strike a drum to mimic explosions.

In the modern version, an electric motor has replaced the clockwork, the acrylic and timber mechanism is laser-cut, and the light sources are now strips of programmable LEDs.

Yet many of the challenges that Hamilton would have faced still remain. The Vesuvian apparatus is a miniature stage set in which the light has to be designed and balanced so that the mechanical elements are not visible to the viewer.

When the University announced a Grand Tour exhibition, it provided an ideal opportunity to create a modern version of Hamilton’s Vesuvian apparatus.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, the extended visit to Italy had become a rite of passage for European nobility and gentry.

They could replay dramatic historical events from their reading of classical authors, attend galleries and churches to view classical and Renaissance art, mix with fashionable society and visit scenic locations such as Vesuvius.

Presented by Archives and Special Collections (ASC), The Grand Tour draws on a recent donation from Terence (Terry) Lane OAM (1946-2024) and brings together artworks, archives and artefacts from the University’s collections.

Sciences & Technology

Probing Earth’s deep and ancient secrets

By including material that relates to Hamilton and his activities in Naples, the exhibition is complemented by Hamilton, Vesuvius and Volcanology, a display of rare books on the ground floor.

Now, 250 years later, like Vesuvius long dormant, Hamilton’s Vesuvian apparatus is erupting in the Baillieu Library.

The Grand Tour exhibition runs from 28 July 2025 to 28 June 2026 in the Noel Shaw Gallery, Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne. A ground-floor display focuses on Hamilton, Vesuvius and Volcanology.