Arts & Culture

Measuring diversity in Australian publishing

Using witness accounts and smuggled information, researchers and technicians have created a 3D digital model of the infamous but dismantled Manus Island Detention Centre

Published 24 November 2021

How can we learn from a site of historical harm if our access to it is denied? How do we uncover the traces of what happened when that place wasn’t only hidden to begin with, but has now disappeared?

Between 2001 and 2008, and again between 2013 and 2017, hundreds of asylum seekers were effectively imprisoned under Australian law, in an offshore processing centre on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea (PNG).

Journalists were denied entry so the evidence of what was happening there had to be smuggled out on hidden mobile phones, often under cover of night.

Those working there were threatened by the Australian Government with two-year prison sentences for speaking out about what they witnessed, under controversial ‘gag’ orders.

Arts & Culture

Measuring diversity in Australian publishing

In 2016, the PNG Supreme Court ordered the detention centre to be closed as its existence breached human rights provisions in the PNG constitution. It was dismantled in 2017.

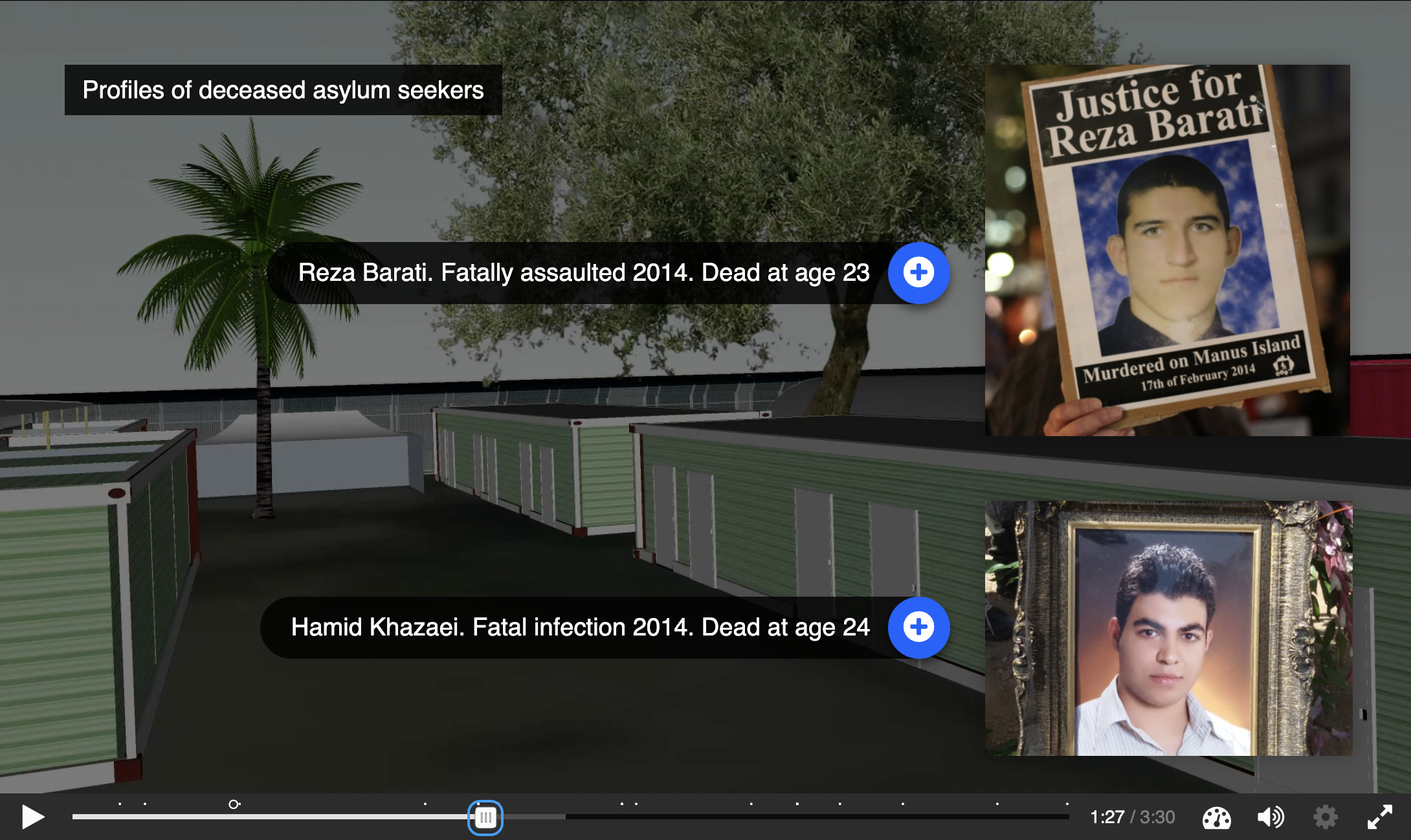

Today, the site is overgrown with forest and jungle. Yet several men died there, due to homicide, self-harm, suicide or untreated medical concerns. Many hundreds of others experienced pain and torture during their imprisonment.

In an effort to preserve the memory of what was done at Manus in our name, we have come together as an interdisciplinary and international research team to build a 3D digital representation of the now dismantled site – Against Erasure.

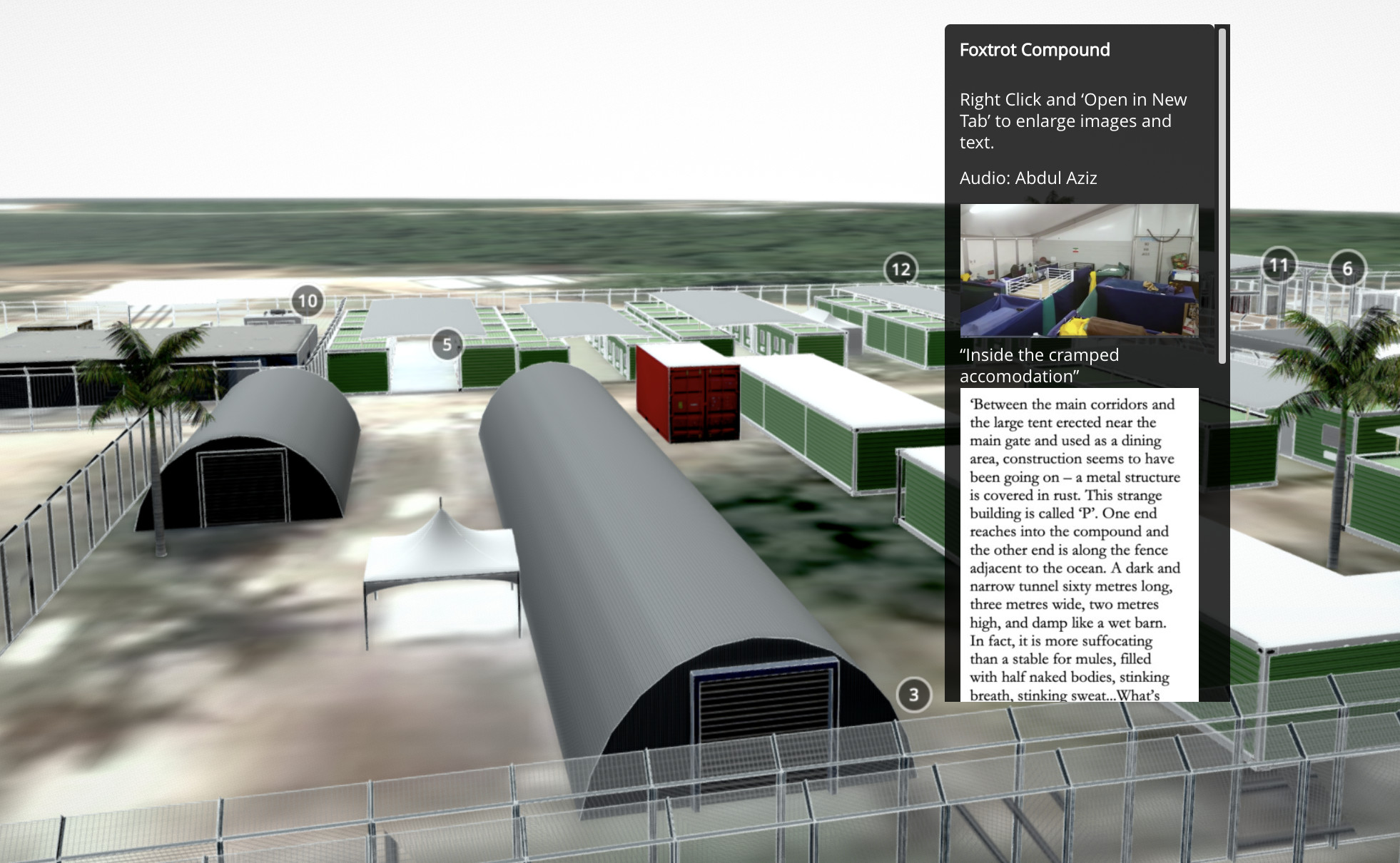

In the absence of most of the buildings and any available plans of the site, we had to reconstruct the detention centre by drawing on archival materials – interviews with Kurdish writer and former detainee Behrouz Boochani, Google Maps, images from the film Chauka Please Tell Us The Time and recordings from the Messenger Project by Michael Green and Abdul Aziz Muhamat.

When Boochani re-visited Manus in 2018 with former migration worker Nicole Judge and refugee activist Ian Rintoul, it was as if the centre had never existed.

As Boochani said:

“The prison had been completely destroyed and was now a jungle with a whole range of plants and other vegetation. I saw the only tree that had existed in Fox prison. I also saw a tree that was in Delta prison, which we called “the suicide tree”. I saw the location of Chauka, the Green Zone, and Bravo, all solitary confinement cells... all these places were now gone; there was not one sign of them left.”

Politics & Society

Racism in sport: So where to from here?

From a technical perspective, the project was unusual. Instead of designing from the ground up, we were piecing together the digital fragments that remained.

We used a 2014 Google Earth satellite image combined with a rudimentary layout diagram from a parliamentary report. Then we reviewed two documentaries for any shots with buildings, fences and doors to infer the height and distances of buildings.

The real breakthrough came when Boochani guided us, building by building, through the entire compound that he knew so well, making sense of the structures and elements, like gates, trees and a soccer field.

Seeing through his eyes how people survived there, how they were separated and controlled – we realised that capturing the human experience within this digital reconstruction was of utmost importance.

The reconstruction of the site is based on a 2014 iteration of the detention centre. We had agreed that the 2014 image, when the prison was crammed with container structures, was the most illustrative of harsh conditions there. But Boochani emphasised that it was always in flux and never permanent.

The site underwent many transformations during its operation. At its peak, it was incredibly crowded, with more than 1,000 men, many camps within a camp and a long perimeter fence through which the men were forced to walk to get to the medical centre.

Arts & Culture

How smaller can be better for memorialising history

The 3D model was imported into an interactive video emulating a drone-style ‘fly-through’. To add the human stories, we added interactive hotspots, profiling the geography of Manus Island, some detainees who died there and some who survived.

Other hotspots provide context through references to activists, media and key Australian political figures who were authors of inhumane laws and policies which make up this country’s border protection regime.

In some ways, the ‘erasure’ of the site is a blessing.

Rather than comprising decaying buildings, the site has been returned to its earlier form, regenerated by jungle – this isn’t a reconstruction of historical ‘ruins’.

But the stories of pain and suffering endured in these ‘erased’ sites continue to reverberate in the present. Honouring the experiences of those who were imprisoned there, has driven this project.

This is the first known 3D model of the detention centre, making a significant contribution to collective knowledge of the facility and the island on which it was based.

In the face of the Australian government’s refusal to acknowledge the harms of its border protection regime, this model is an historical reminder of, and testament to, the lives and suffering of those imprisoned there – a violent effect of Australian laws and policies.

‘Against Erasure’ was led by criminologist Dr Claire Loughnan and historian Dr Una McIlvenna, with team members Jordy Silverstein, Mahnaz Alimardanian, and Uma Kothari, and the expertise of Sam Taylor, Mitch Buzza and Meredith Hinze from the University of Melbourne Faculty of Arts eLearning/eTeaching Team.

Against Erasure will be launched at webinar on 25 November, 2021 with guest speakers Behrouz Boochani, Arash Kamali Sarvestani, Shaminda Kanapathi and Ben Doherty.

Banner: Recreated view from Route Charlie, Manus Island Detention Centre/Supplied