Arts & Culture

10 great books you should read in 2017

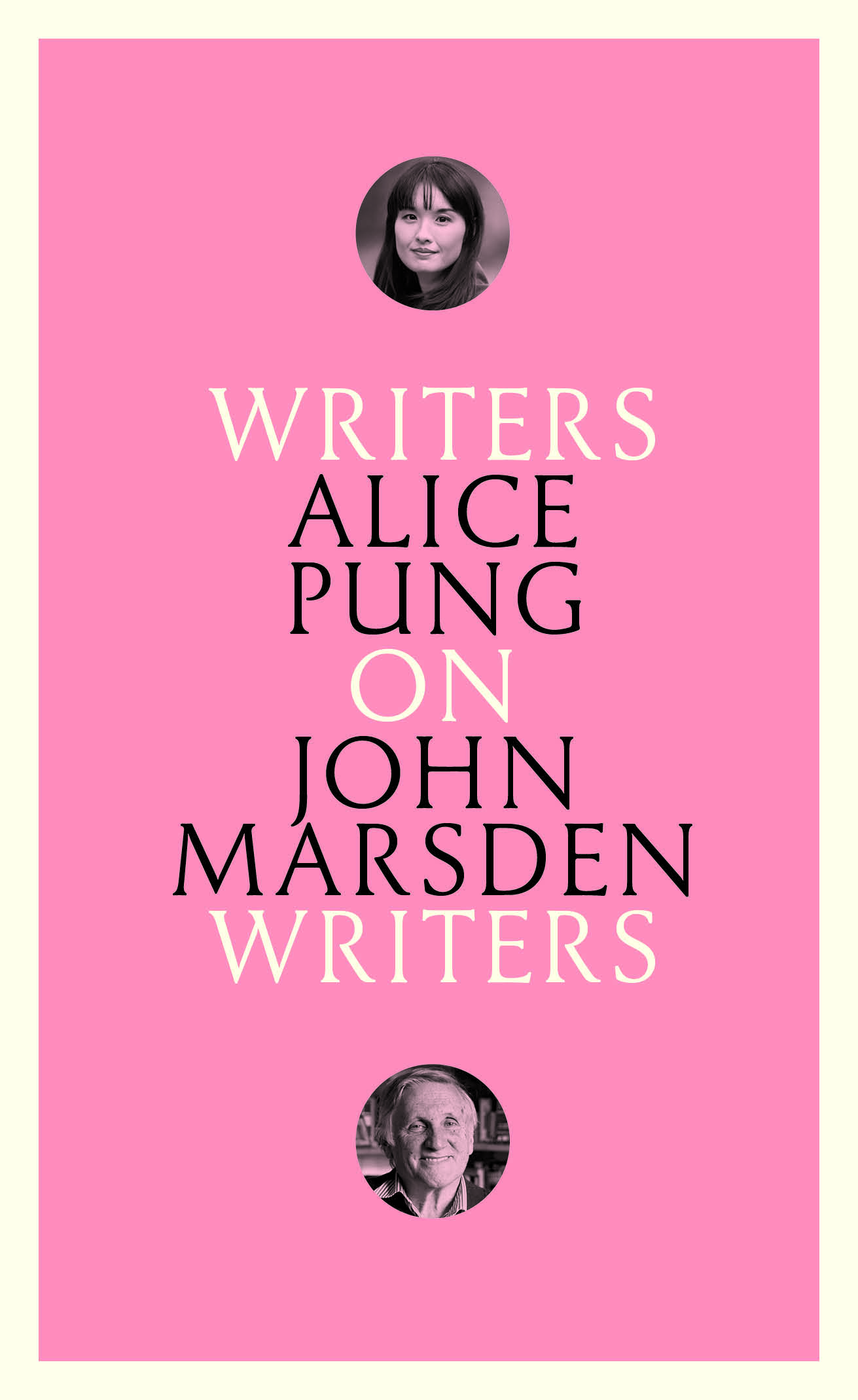

In a collaboration between the University of Melbourne, the State Library Victoria and independent publisher Black Inc called Writers on Writers - modern authors reflect on the influence of those who came before them. In this book extract Alice Pung writes to her literary champion, John Marsden.

Published 1 October 2017

Dear John,

The first time it occurred to me that you were a real person was the morning my friend Angela came to school and said, ‘You’ll never believe what happened. We bumped into John Marsden.’

‘Nooo way!’

To us, you weren’t real, and if you were, you weren’t someone who’d be loitering in the western suburbs of Melbourne. But Angela meant it literally: her mum had bashed her car into yours somewhere down the Tullamarine Freeway, and you were so kind about it you even gave them some of your books.

We all knew of you, but not about you. We studied So Much to Tell You during the first term of Year 9 at Christ the King College. Our parents had sent us to the Catholic school in Braybrook to save us from temptation. Fortressed by a wall of carpet factories and sequestered next to a nunnery, we studied in an oasis of industry and restraint in one of the roughest neighbourhoods in Victoria. In primary school, when one boy fractured another boy’s wrist, my best friend spent all lunchtime trying to convince the victim not to dob on her brother.

Arts & Culture

10 great books you should read in 2017

Another of my ten-year-old friends saw the counsellor every week because her stepfather kept ‘mucking around’ with her. One recess, the boys from the technical college just over the fence from our school found a bird with a broken wing, brought it to the Preps and then snapped its neck in front of them. We called kids ‘bin scabs’ if at lunchtime they yanked food out of bins to eat, because we thought that was a normal quirk of childhood, a habit no different to picking actual scabs – disgusting, but not a sign of any larger tragedy, like not having enough food at home.

This is all a bit bleak, isn’t it? Maybe I should have started by hailing the heroic females in your novels, and how they gave me girl power. But that would be a lie because the characters in your novels I most identify with are not ‘heroic’, nor are they always female. I could mention your children’s picture book Millie, to soften things up a bit for the reader.

But, John, even your children’s books piss people off! ‘Millie is an odious, conniving, lying child, who gets away with all her hideous behaviour,’ writes one reviewer. ‘Even when she’s caught in the act everyone just says “we all love Millie”? Oh please.’ Millie’s transgressions include brushing her dog’s teeth with her own toothbrush and resourcefully hiding everything under the bed when asked to tidy up. I guess the problem with your stories is that you don’t include the punishment at the end.

In high school a friend was reading The Dead of the Night, and our science teacher wryly remarked, as he looked at the back cover, ‘I presume this will be filled with violence and sex and the usual teenage preoccupations.’ Yes, it was, and yes, we were very preoccupied with them. We thought they were far more fascinating than the usual ‘adult themes’ that people around us were constantly discussing: overtime, tax and rent.

Your books appealed to us because they made our experiences central. Children and young adults often don’t have the words to describe what is going on inside them. Even when they do, their stories are translated and interpreted by adults in a way that bears scant resemblance to lived experience. But you kept it real, so real that even your first publisher, Walter McVitty, who took such a risk with So Much to Tell You, felt ambivalent about your later books:

To have turned so many children on to reading is a wonderful thing to have achieved, I think. And yet, if I was asked, would I like my little grandchildren to be exposed to those books, maybe I would say no. I just feel that the mind of a young person is such a malleable thing, I would want them to grow up in as uncorrupted a world as possible. I don’t feel as though I want to be rubbing my children’s noses in it.

I wonder what you are rubbing children’s noses in? Could it be Australia’s colonial history (The Rabbits), the effect of political corruption on families (Checkers), the loneliness of juvenile detention, or the terror of not having your abuse taken seriously (Letters from the Inside)? Maybe it’s the inordinate blind rage of being from a poor background who no real life prospects, and on top of that dealing with a disability (Dear Miffy), or the effects of wartime post-traumatic stress (the Tomorrow series)?

You once pointed out that childhood and adolescence are when a person has the most number of first experiences, and perhaps that’s what people mean when they say that the young are ‘impressionable’. But then you added, ‘If you’ve ever tried to persuade a three-year-old to eat spinach you’ll soon see how impressionable they are.’ And you mentioned that plenty of adults are impressionable – Hitler, Pol Pot and Jim Jones had no trouble finding disciples among the old and middle-aged.

Much of the time, I reckon stories about children are an ‘adults-only’ fantasy of childhood, revealing more about the writer and their projections than the truth of their subjects. In 1992, Susan Orlean wrote her famous profile for Esquire, ‘The American Male at Age Ten’, which now reads like an early ‘90s list of a ten-year-old boy’s consumer preferences – Morgan Freeman movies, Nintendo, Streetfighter II.

It begins, ‘If Colin Duffy and I were to get married, we would have matching superhero notebooks…We would eat pizza and candy for all of our meals. We wouldn’t have sex, but we would have crushes on each other and, magically, babies would appear in our home.’

The piece was groundbreaking because it was the first time a famous international magazine had published a piece about the interests of an ‘ordinary’ kid that was written with the same focus of intensity and analysis as an interview with the president.

But to me, reading it now, it really grates, especially when Orlean observes: ‘That ten-year-olds feel the weight of the world and consider it their mission to shoulder it came as a surprise to me.’ What world is she living in? Apparently a world where ‘Colin loves recycling. He loves it even more than, say, playing with little birds.’

Perhaps it’s those who are charmed by stories like Colin Duffy’s, seeing them as signs that our future is in ‘good’ hands, who have the most trouble with your books, John. Your fiercest critics are probably those who have the luxury of thinking that childhood should be free of anxiety, worry, sadness, illness, stress and grief – emotions that every child feels at some point or another.

You once said about Letters from the Inside: ‘I was struck, as I have been many time since, by the fact that young readers react so differently to older readers, but older readers don’t seem to notice that.’

Writers on Writers is a series of six short books, where each author reflects on another Australian writer who has inspired and influenced them. The books are available for purchase here.

Commissioned writers are Erik Jensen on Kate Jennings (Oct 2017); Alice Pung on John Marsden (Oct 2017); Christos Tsiolkas on Patrick White (May 2018); Nam Le on David Malouf (May 2018); Ceridwen Dovey on JM Coetzee (Oct 2018);Michelle de Kretser on Shirley Hazzard (Oct 2018).

Banner image: The Rabbits/John Marsden and Shaun Tan