Business & Economics

Millennials want the same as the rest of us, but can’t afford it

As Melbourne’s population hits 5 million, with the largest annual increase of any city in Australia’s history over the last year, Victoria must use its land wisely to meet the growing need for affordable housing

Published 7 September 2018

As of late August, Greater Melbourne officially became home to 5 million people – that’s almost 90 per cent of the state’s population. With these figures in mind, the State Government is taking important steps to address the growing affordable housing crisis.

According to the amended Planning and Environment Act 1987, affordable housing is “housing, including social housing, that is appropriate for the housing needs of very low, low and moderate-income households”.

And Victoria faces a dire shortage.

Since Plan Melbourne, the metropolitan planning strategy, and Homes for Victorians, the affordable housing strategy, both launched in February 2017, affordable housing has been included as an crucial aim of the Planning Act.

This will allow voluntary agreements with developers to provide five to 10 per cent of new dwellings that will be affordable to very low, low and moderate income households.

Business & Economics

Millennials want the same as the rest of us, but can’t afford it

An Inclusionary Zoning pilot on government land will result in “at least” 100 affordable housing units and private development-led Public Housing Renewal will result in “at least” another 1,100 units.

But given the scale of the problem, how much difference will this make?

When these strategies were released, we argued that the very modest goals in the affordable housing strategy of 4,700 dwellings between 2017-22 are a just one drop in the bucket.

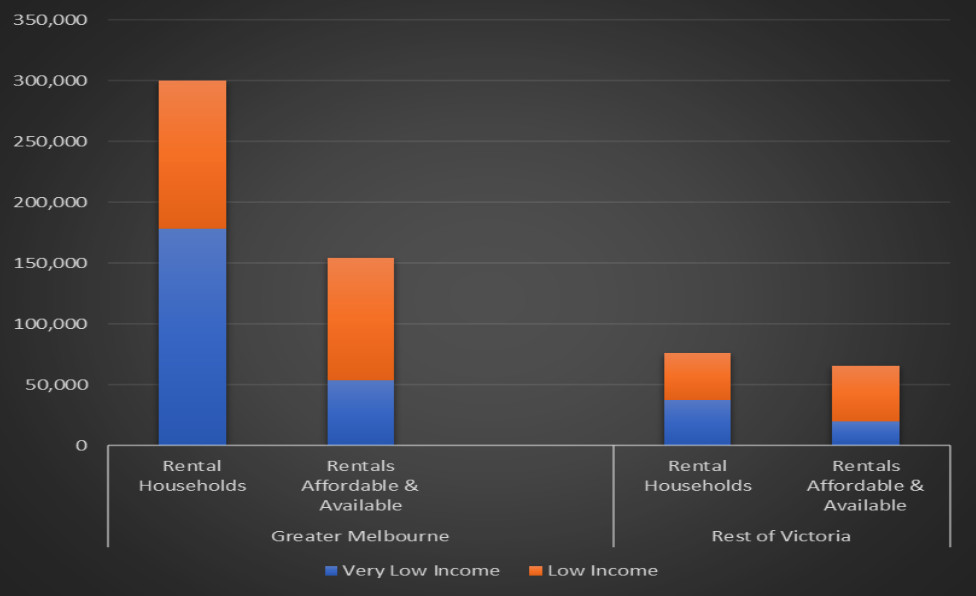

According to our report, Victoria faces a deficit of roughly 164,000 affordable homes for very low and low-income households - and this doesn’t account for population growth of over 2 per cent per annum.

We have compared the number of very low and low-income households with the availability of affordable units in order to highlight the sheer scale of the issue.

To make a real difference to housing stress and the risk of homelessness, Plan Melbourne’s commitment to using vacant or under-utilised government land needs to be scaled up and re-focused. Victoria has the opportunity to gain much more social benefit from its public land assets.

If we look at Vancouver in Canada, their 2017 Housing Strategy commits the equivalent of 300,000 dwellings for lower income households by 2027. An essential part of this strategy is using all suitable and well-located vacant and under-utilised government land.

In April 2018, Vancouver also committed to provide 600 units of modular supportive housing for homeless people on vacant government land. By the beginning of August, half of these units were complete or under construction.

Business & Economics

Is rent-for-life becoming the new norm for families?

Our new report provides details on where, why and how government land could be used to boost affordable housing. As part of that process, we have mapped 195 hectares of government-owned land across 255 sites (see map below).

We started with a dataset of over 12,000 government-owned properties identified through title searches and Freedom of Information Act Requests.

We limited our search to government sites that were surplus, vacant or ‘lazy’ – ’lazy’ land already houses low-rise facilities like community centres, health clinics, libraries, government offices, carparks and childcare centres but is also compatible with accommodating affordable housing. We excluded any parkland or green space.

We then limited our search to sites that scored highly on our Housing Access Rating Tool (HART).

HART is a 20-point tool that measures critical amenities and social services within walking distance of each parcel of land and takes its inspiration from the 20-minute city concept in Plan Melbourne. We included public transport, childcare centres, public schools, parks, libraries, grocery stores, community centres and healthcare services.

It will come as no surprise that land costs are highest in the city centre and inner suburbs where existing transport and services are strongest.

This makes it difficult for non-profits to develop social housing in these rapidly gentrifying areas. In fact, Australian research suggests land costs can consume up to 30 per cent of the cost of development.

Construction and building permit exemptions, expedited planning permits, low-rate construction loans and mortgages as well as ongoing Commonwealth Rent Assistance subsidies attached to projects can all contribute to further reduce affordable housing costs.

Cause We Care House in Vancouver is an example of creative use of ‘lazy’ public land.

There’s a library located on the first floor which is topped by five floors of housing for women escaping domestic violence.

Through a combination of local government land, senior government subsidy and philanthropic donations 21 mothers and their children have found stable and secure housing as a result of the project.

Currently, we are working with the Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation and the City of Darebin on an Affordable Housing Challenge to build philanthropically-funded social housing on a local government car park close to Preston Market; this kind of housing that sits above car parks has already been successfully trialled by the City of Port Phillip.

Non-profit housing providers, architects and builders have the expertise and experience to rapidly scale up affordable housing in fast-growing cities like Melbourne.

So, what are we waiting for?

This is an edited version of an article co-published with The Conversation.

Banner: Getty Images