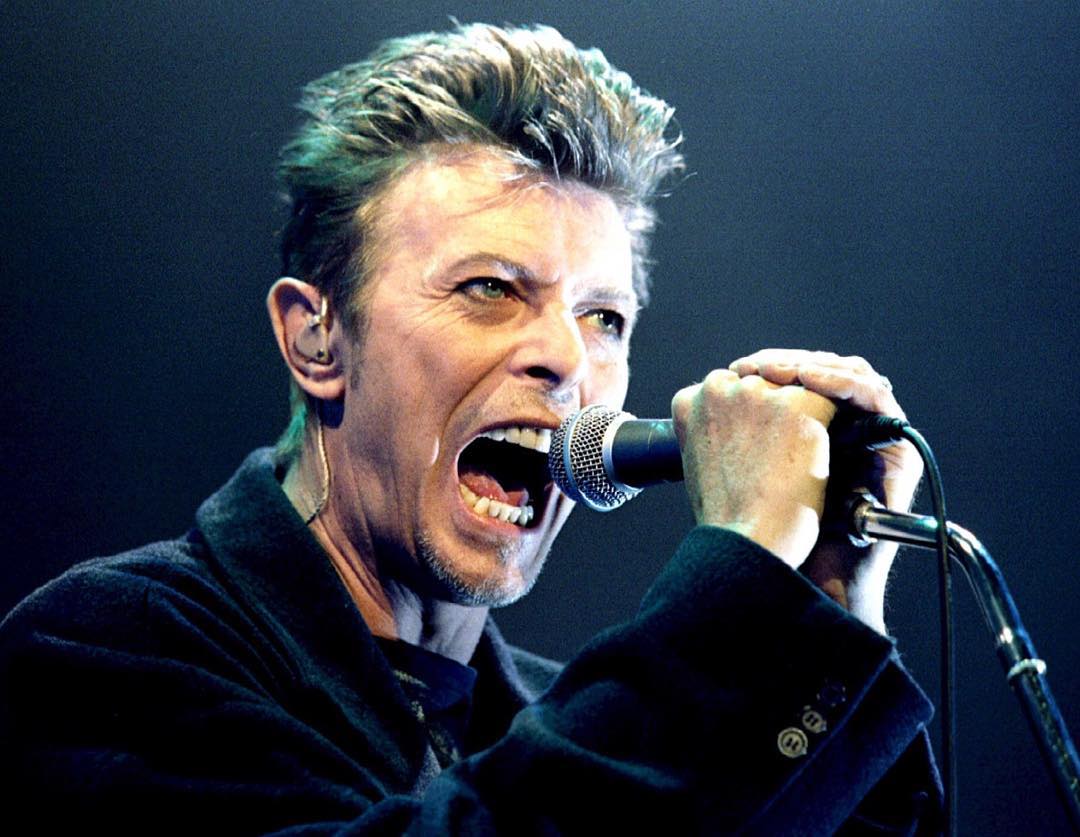

An icon who collected sounds

David Bowie taught us how to listen to music we thought we already knew

Published 12 January 2016

Pop stars are too often mourned as historical objects. At worst, they become museum pieces repolished for burial, with eulogies focusing on hyperbolic turning points (“the first person to...”) and twilight accolades.

For the Baby Boomer superstars who crowd the rock museum, generous biographers will overlook the Not-Quite-Disco Album, the Half-Tempo National Anthem At Major Sporting Event and the Lawsuit To Protect Rebellious Teen Anthem From Copyright Infringement.

David Bowie never became an historical object – he was always walking on this side of the exhibition. He’d stroll with us, listening and pointing, making jokes and winking at old friends. Bowie was a musical curator, collecting sounds and people. Bowie famously saved Lou Reed and Iggy Pop from fumbling solo careers, rescued guitarist Mick Ronson from the doldrums of sessional recording, and perfected with Brian Eno the quintessential crooner-meets-Krautrock anthem.

But the collecting of sounds was still more exciting.

Bowie listened to popular music. From The Laughing Gnome (1967) to the unsettling farewell, Blackstar (2016), he kept listening. This banal fact cannot be said for most artists of Bowie’s stature, and should continue to blow our minds.

As an obsessive listener Bowie taught us how to hear popular music we thought we already knew. Who can revisit T. Rex’s rock breakthrough Electric Warrior (1971) without hearing the affectionate tributes on The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972)?

For the same reason, Let’s Dance (1983)is a great disco record by someone listening to disco. Outside (1995) was an industrial pop record by someone who noticed that grunge was giving way to something much darker, much more daringly solipsistic, and much less nostalgic for the rituals of rock.

And The Next Day (2013) is Bowie listening to Bowie as a critic might, selecting out the bits that were underdeveloped in the late 1970s, and leaving alone everything that needed to be left alone. You can make any music you want, Bowie’s catalogue tells us, as long as you keep listening to music and listening properly.

Bowie’s politics were always tied to this power of careful listening and mimicry. He knew how to inhabit unfamiliar, unsettling and unwelcoming spaces, and how to “pass” using different masks, some more durable than others.

Bowie’s status as a queer icon is less linked to interminable gossip about affirmations and disavowals of homosexual identity, and more to his savvy in discovering pathways through the hostile landscapes of Album Oriented Rock in the seventies.

When first wrestling with the rock canon on The Man Who Sold the World (1970), he put a dress and lipstick on it. Even more rewarding, however, was covers album Pin Ups (1973), where Bowie re-scripted the British Beat era, from a story about heterosexual male R&B groups climbing toward stadium glory, to a flamboyant melodrama splashed with equal measures of camp pleasure, earnest nostalgia, and hard rock pantomime.

It wouldn’t make sense to label this early 70s Bowie a certain type of masculinity or sexuality. His innovation was simply to make available entirely new ways of feeling pleasure in inauthenticity, and new ways to move between social identities without having to explain oneself.

But already I’ve overstepped the line. More than most, meta-narratives about Bowie’s music always invite counter-narratives, counter-canons, second and third and fourth listenings.

This is why I want to finish on the topic of Bowie fandom, which is essential to the cultural life of Bowie himself.

Conversations about Bowie with Bowie fans are entirely different from conversations about other pop stars. Bowie fandom doesn’t tell you anything about a person’s musical taste. Watch tributes flood into your social media newsfeed from metalheads, folk lyricists, bush doofers and retired ravers, people who don’t care about music, and people who only care about music. Sid Vicious from the Sex Pistols loved Bowie – and why not?

Bowie fans have to become as supple as Bowie himself, bending to each new album. Conversations about Bowie must therefore be about how to listen to Bowie. Is there a secret relationship between the wandering Americana of Hunky Dory (1971), the metropolitan instrumentals of Low (1977), and the bombastic clunk of the Tin Machine debut in 1989?

Even if we confine ourselves to the acclaimed hits from 1969’s Space Oddity to Let’s Dance in 1983,the canon is constantly warped across weirdly shaped objects.

Bowie fandom is bound by this warpedness and weirdness, this shared experience of trying to pin down a moving target, and the thrill of seeking fidelity to a self-confessed fake.

Of the pop artists who could have marked an unexpected death with the appropriate cocktail of sincerity, cliché and ambivalence, Bowie was the best suited.

There is no anthem from Bowie’s repertoire that could be a funeral march without also intimating, in the same breath, that the game has been rigged, that the words have been stolen, and that the funeral is full of phonies.

Which is just fine as long as we listen to Blackstar and listen often, because that’s what Bowie would do.

Banner image: A streetscape advertising the “David Bowie” exhibition in Berlin. Picture: 360b/Shutterstock.com