Politics & Society

What happened in the US was Very Bad

The storming of the Capitol in January followed a serious intelligence failure. A new report on analytical rigour helps explain how to do better

Published 11 June 2021

The storming of the US Capitol on January 6th of this year was enabled, in part, by one of the most striking intelligence failures of recent times.

The problem was not in the intelligence collection. The necessary information was abundant, easily obtained, and being gathered by many well-resourced people and organisations.

A key problem, according to the Senate Report, was that the most directly responsible agencies, such as the Office of Intelligence and Analysis in the Department of Homeland Security, failed to attend properly to the information and inform decision-makers (though see here).

In this regard, it’s similar to the intelligence failure leading to 9/11.

Politics & Society

What happened in the US was Very Bad

The 9/11 Commission identified a lack of rigour in intelligence analysis as a key contributor. These events led to the establishment of a new agency, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, which soon issued Directive 203 aimed at promoting “analytic rigour and excellence.”

But what exactly is analytic rigour?

Despite its importance, this topic has received surprisingly little attention. There has been much discussion of factors that seem to harm it, and how organisations might improve it, but there has never been a widely accepted, well-grounded account of what analytic rigour actually consists of.

In 2020, our group, the Hunt Lab for Intelligence Research, tackled this problem head-on.

In an intensive six-month project, funded by the National Security Science and Technology Centre, we developed an account of analytic rigour, based on three processes: a systematic literature review, an expert panel, and a survey of staff in an intelligence agency. The results of these processes were then merged into a single synoptic view.

Setting out on this project, we faced a paradox.

We would have to conduct our own work with exemplary analytic rigour. But as the premise of the project was that rigour was not well understood, how then could we rigorously investigate rigour?

Sciences & Technology

Crowdsourcing security intelligence

Our approach was to use a kind of bootstrapping. This means that we started with an initial grasp of rigour, shaped partly by our training in analytic philosophy.

We used this to design our processes to be as rigorous as possible, given the constraints. We used these processes to develop an account of rigour, which we were then able to apply back to our own work before delivering our final report.

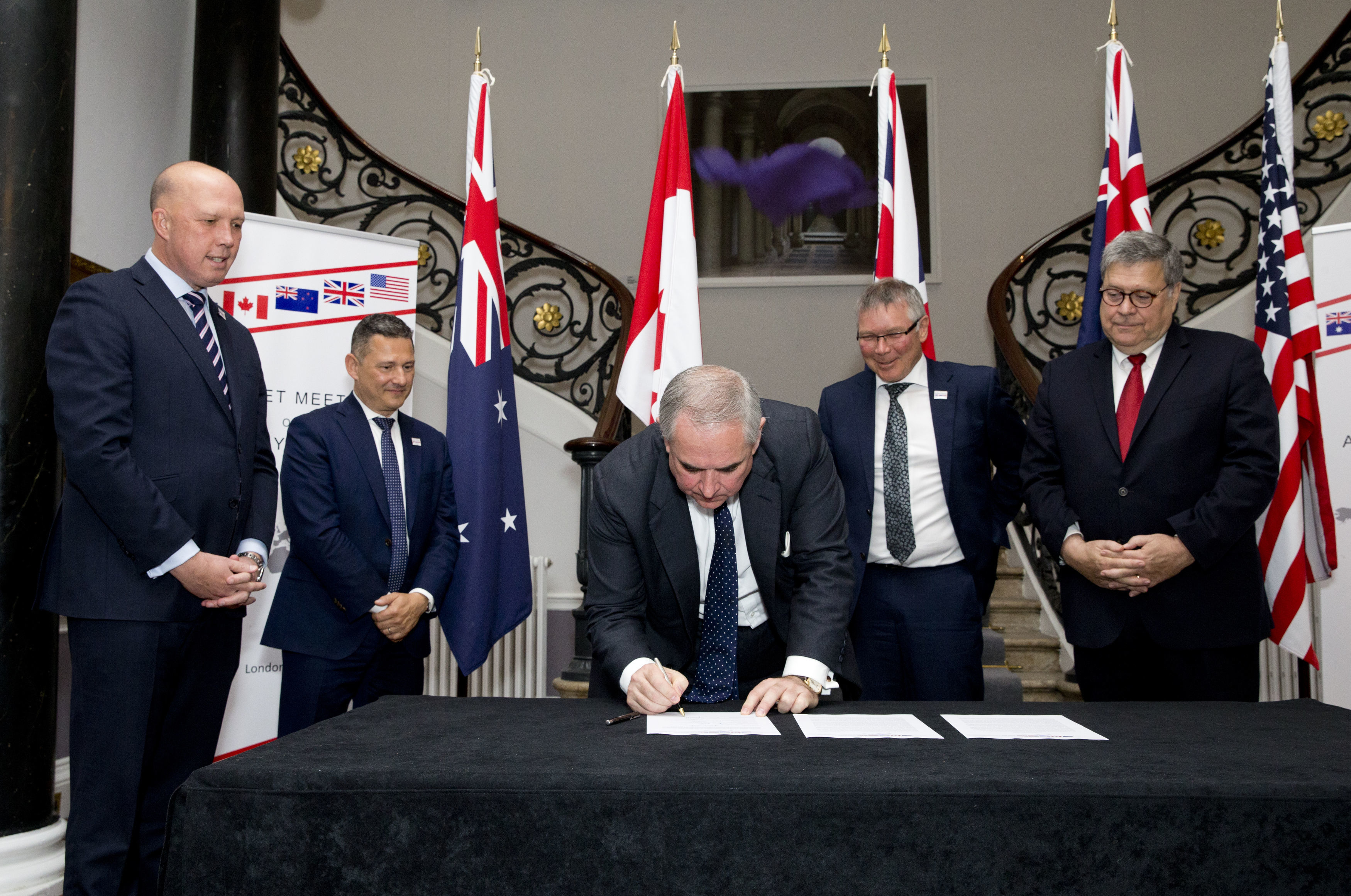

Conducting the expert panel process was an interesting challenge. We wanted to articulate the collective wisdom of an international pool of 65 experts, including intelligence practitioners and academics, drawn mostly from the Five Eyes alliance made up of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The process had to be entirely online and take no more than a month. We used a version of the well-known Delphi process to identify what views were collectively held and the strength of agreement for each such view.

At the outset of the process, every expert provided a set of statements representing what they thought was most true and important about analytic rigour. Reviewing these statements, it was clear to us that the experts all held incomplete and eclectic perspectives, notwithstanding their enormous experience and sophistication.

However, implicit in the union of all of these perspectives was a rich shared understanding. It was a classic case of the blind men and the elephant, the famous parable where six blind men each get a limited understanding of an elephant by touching a different part.

But in this case, we could merge the views to reveal the true nature of the beast.

And, so what is analytic rigour? In our view, it is best understood as observing the “LOTSA” rigour principles:

1. (L) Logicality, in observing the principles of good reasoning and avoiding fallacies

2. (O) Objectivity, in avoiding the inappropriate influence of interests and values

3. (T) Thoroughness, in tackling analytic work with completeness and attention to detail

4. (S) Stringency, in following relevant rules, guidelines and procedures

5. (A) Acuity, in noticing and addressing relevant issues and subtleties, including those others might have missed.

This is of course a very high-level take.

Analytic rigour in intelligence work specifically means applying the LOTSA principles in all important aspects of that work. This can be articulated in considerably more detail – indeed some useful work of this kind was previously done at Ohio State University.

We believe that the LOTSA definition also applies to many other kinds of analytic work, well beyond intelligence. For example, science and tertiary education, both aspire to analytic rigour. In both cases, to be rigorous is to be logical, objective and so on.

So, our report on analytic rigour in intelligence might be helpful in many situations where there is a need to be more, well, rigorous in thinking about rigour.

This research was a collaboration between the Commonwealth of Australia and the University of Melbourne.

Banner: Getty Images