Sciences & Technology

TikTok captures your face

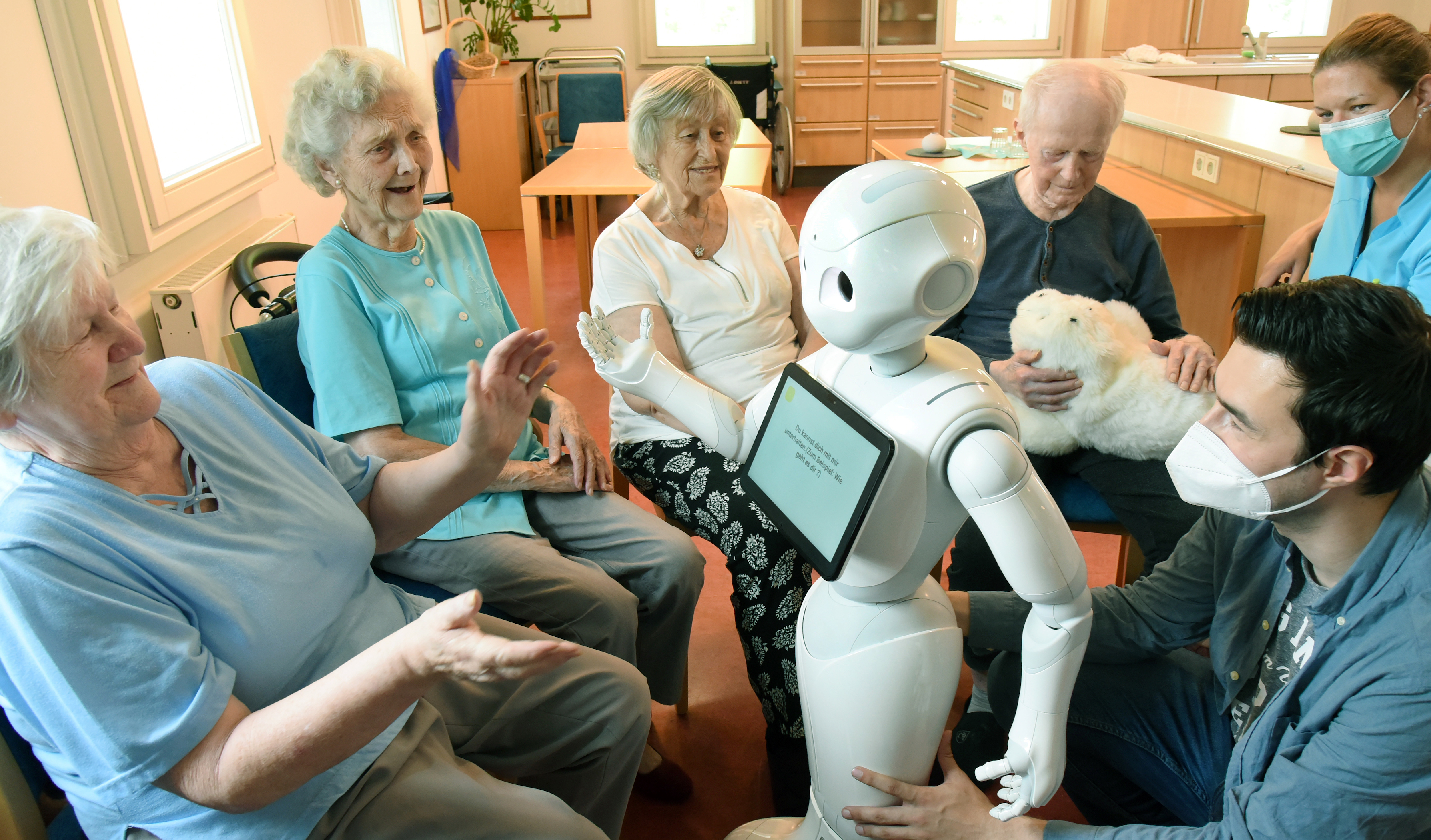

Care robots may be a safer option in aged care during pandemics like COVID-19, but how far can robotic care go and how far do we want it to go?

Published 28 July 2021

In an echo of last year’s devastating COVID-19 outbreak in Victorian aged care homes, the virus recently struck aged care in New South Wales, leaving people fearing for older parents and friends.

The care staff in the NSW outbreak, many of them unvaccinated, posed a transmission risk to residents. Meanwhile, the industry is also facing staff shortages that are set to be exacerbated by rising demand and a looming shortage of younger workers as the population ages.

This raises the question of whether robots might help in caring for humans. For example, properly cleaned care robots would not transmit COVID-19 the way humans do.

But the idea that future robots might do care work is controversial. Are robots the answer, or a threat to the future of care?

Sciences & Technology

TikTok captures your face

Some people may have encountered simple types of care robots. Robots are already used in homes and healthcare systems around the world.

ElliQ is a talking bot with a tablet designed to interact with older people. Care-O-bot has pivoting joints and can fetch objects and answer questions.

RIBA, with its friendly bear-like face, can pick people up and carry them around a hospital or care home. While Kasper, a friendly childlike robot, helps children on the autism spectrum develop their social skills.

Our recently published study, ‘Robots and the Possibility of Humanistic Care’, examines the potential of robots to provide not just functional care – like cleaning, lifting, feeding, and taking blood pressure – but also the affective care we tend to think only a human can provide – like comfort, reassurance or company to anxious, ill or lonely people.

Often function and affective care go together – for example, when a nurse takes our vital signs while kindly asking us how we are feeling.

So, could robots also provide affective care as well as functional care?

To a degree, this already happens.

Research suggests that robots like Paro, the fluffy baby seal robot who provides “unconditional love for residents with dementia”, can help aged care residents to feel less anxious or lonely and lift their spirits.

Sciences & Technology

You wouldn’t hit a dog, so why would you kill one in Minecraft?

Care robots are efficient and untiring. They are potentially less obtrusive than humans and might afford patients some more privacy and dignity in washing or using the bathroom.

And as technology progresses, robots will become more lifelike. Instead of having shiny hard surfaces, they may have soft and supple ‘skin’. Future robots could also have faces that are more expressive of moods and feelings.

Artificial intelligence should enable future robots to recognise individuals and their emotions, and to engage in more natural conversations.

Care robots may begin to resemble the kind nurse who speaks reassuring words to comfort anxious patients.

Yet, humanoid care robots also cause skepticism and alarm. For example, there seems to be something special about care that is distinctively or uniquely human. A ‘humanistic’ caregiver does not only provide functional care and display some concern, but also shows human forms of deep, sympathetic understanding.

Humanistic care could involve showing human solidarity and expressing to a sick or isolated person the idea that they are a fellow traveller in life. These kinds of expressive acts can comfort and console partly by reminding the other of their own precious humanity.

Arts & Culture

Your face is muted

Some humanoid robots may compellingly mimic humanistic care. Their bodies may resemble human bodies and their gestures and words may appear to express human understanding and sympathy.

But, as we know, robots do not have actual human bodies or human understanding. They can only simulate human aged care workers, nurses or doctors.

Many people could be repelled by humanlike care robots, including people who distrust technology.

Nonetheless, robot care that resembles humanistic care might provide comfort to some sufferers. Having a low-risk workforce on standby for crises, like COVID-19, could help protect our most vulnerable.

Even so, there are real concerns that robots could put carers out of work and replace the ‘human touch’. Once humanoid care robots are deployed, it might be hard to roll them back.

What seems necessary in a pandemic could become normalised in aged care and hospitals, and future pandemics are bound to arise.

Health & Medicine

Using AI to predict hospital costs in real time

As robots become better mimics of humanistic care, society might want to consider if and how they might be used. Some people may come to regard robots that can safely take blood pressure, change the bedpan and offer a joke or a thought that evokes a sympathetic human presence as something they need, and even have a right to.

However, no-one should be coerced into accepting robot care.

After all, some patients and aged care residents will find robot caregiving creepy and unsettling. And ensuring that robots don’t undermine genuine human care remains essential.

Banner: Getty Images