Health & Medicine

What’s the right COVID-19 risk to live with?

Arbitrary caps on numbers and mandatory hotel quarantine for even very low-risk international arrivals is irrational and costly. And a lost opportunity

Published 2 August 2021

Australia’s low vaccination coverage is currently holding back the reopening of our domestic and international borders.

And it will be some months before 70 per cent of Australian adults will be vaccinated – this is the new target set by Government before international arrival caps can return to what they were a couple of months ago, along with increased capped entry of student, economic and humanitarian visa holders.

At 80 per cent adult vaccine coverage, caps on returning vaccinated Australians will be abolished, new travel bubbles will be opened and other loosening of borders will occur.

The National Plan is a good skeleton but, it needs further nuance when it comes to fleshing it out.

The good news is that we can already safely and strategically open or relax borders restrictions with select low-risk countries.

Health & Medicine

What’s the right COVID-19 risk to live with?

The plan talks about differentiation of rules by country of origin (or ‘safe countries’) once we get to 80 per cent vaccine coverage. But we already know enough to safely move away from a one-size-fits-all international border policy now – or sooner. And we have some experience already.

For example, we have paused arrivals from high risk countries like India, while allowing quarantine-free arrivals from low risk countries like New Zealand.

By utilising other tools, like pre-departure testing and vaccination, we could now safely accept arrivals without hotel quarantine from some selected low-risk countries.

This would come with significant economic and social benefits to Australia.

Did you know that the chance of a COVID-19 outbreak arising from an international arrival from China (or other low prevalence countries) – with no quarantine – is far less than the chance of an outbreak arising from a British arrival who completes their 14-day hotel quarantine? Way less.

How can this be? Because the risk of COVID-19 incursions is – first and foremost – proportional to the infection rate in the country of origin, as our calculator shows.

In China, there is minimal community transmission, whereas Britain is still struggling with ongoing transmission.

Many arrivals from Britain will develop COVID-19 during their hotel quarantine stay, and because for every 192 infections managed in hotel quarantine a community outbreak occurs, this risk exceeds that from the same number of arrivals from China completely bypassing quarantine.

Health & Medicine

How long till Sydney gets out of lockdown?

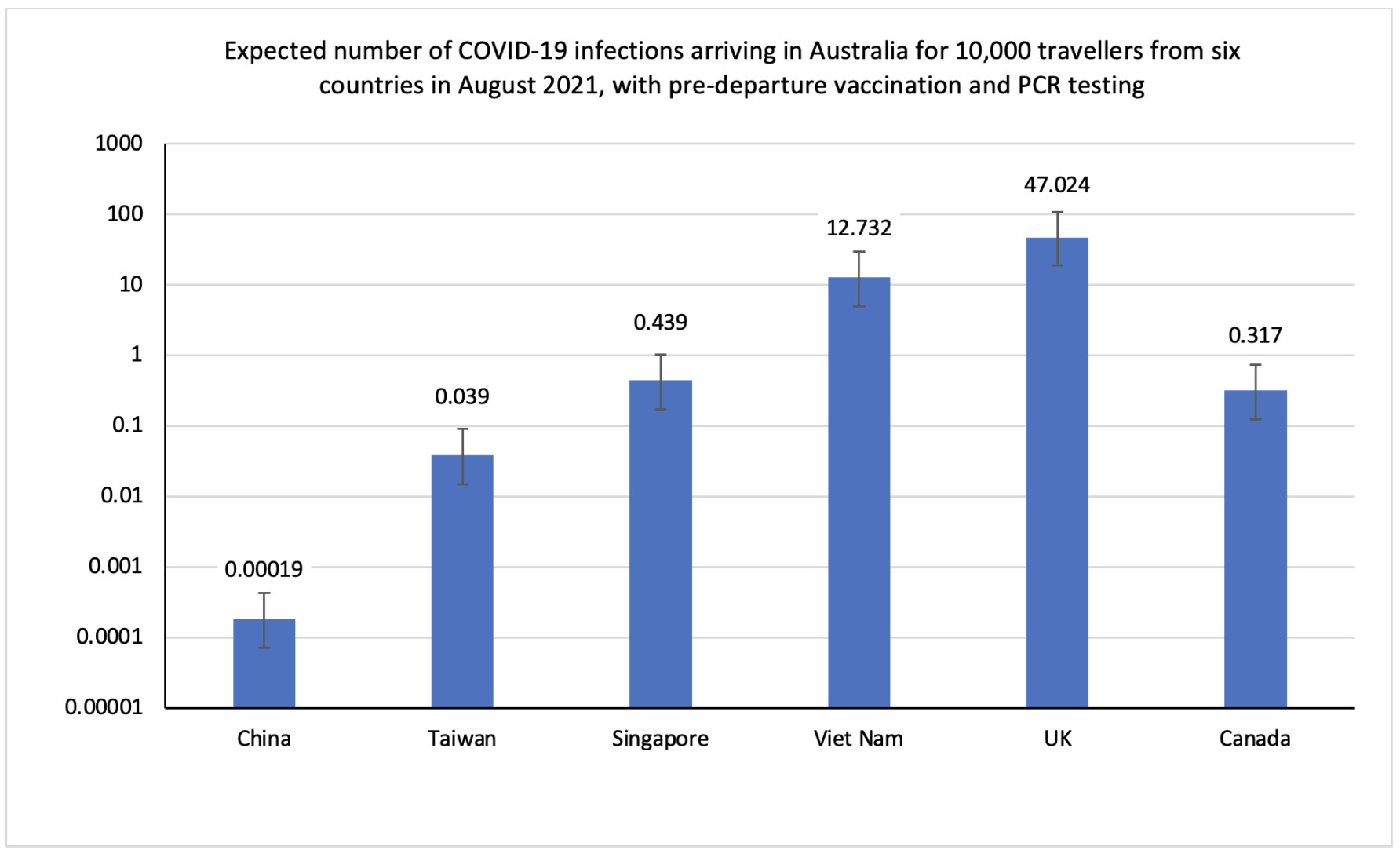

Let’s do the math for arrivals from six countries: China, Vietnam, Taiwan, Singapore, UK and Canada.

First, we need reliable estimates of true infection rates in these countries.

The Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) perhaps most accurately predicts true infection rates by utilising excess death rates and antibody surveys to supplement the number of officially reported cases. In countries like India, this could be 50 times higher than official data.

Now, let’s imagine that 10,000 people were randomly selected from these six countries to travel to Australia in July 2021.

All travellers would be vaccinated which reduces the risk of any infection by 70 per cent – this is the average effectiveness of vaccines at reducing infection.

Next, we require PCR testing for COVID-19 before travelling.

If any infected person remains among the 10,000, then it’s likely some will be close contacts of a case and prevented from travelling – further reducing the risk.

The figure shows the expected number of infected arrivals out of 10,000 travellers from each country (assuming no transit).

Politics & Society

Get ready for a shift in the COVID blame game

From China its essentially zero – or 0.00019 positive cases per 10,000 arrivals. It would take 52.6 million arrivals before we expected just one case of COVID-19 to arrive on our shores.

This ‘low-risk’ strongly supports allowing quarantine-free arrival from China and other similarly low prevalence countries – subject to ongoing verification that rates are truly low in China. Passport checks would be required to ensure people have not transited from a higher risk country in the previous two weeks.

In fact, with such a low risk, when these travellers use hotel quarantine, they significantly increase their risk of infection due to potential exposure from other returning travellers.

And for arrivals from places like Singapore (0.439 cases / 10,000 arrivals) and Taiwan (0.039 cases/10,0000 arrivals) we could reduce the risk of an outbreak with additional measures – like rapid antigen testing – just before boarding the plane, further testing on arrival, monitored home isolation with PCR test on day five, and compulsory mask wearing.

These low risk countries could be granted earlier staggered entry to the trials and caps outlined in the National Plan. Treating all countries the same is illogical.

Any plans to bring in people without quarantine, or reduced quarantine, from very low risk countries must be informed by real-time data and allow for the ramping up or down of measures (or even pauses) – as with our domestic borders and travel bubble with New Zealand.

Those countries that have ‘green light’ status will need to be constantly reviewed.

But quarantine rules for non-resident arrivals regardless of the country of origin, when the risk of an outbreak for quarantine-free arrivals from very low prevalence countries is essentially zero, is irrational.

And a lost opportunity.

A version of this article was first published in the Australian Financial Review.

Banner: Getty Images