Bad films need to be called out each year

If we are going to salute the year’s best, it makes sense to do the same with the year’s worst films

Published 25 January 2016

It didn’t make my Best of List last year – let’s not go crazy – but I quite enjoyed Spectre. Only the second Bond film I’d seen, but I found myself suitably sucked in.

Had I set myself the task afterwards, however, of having to write something about it – if I’d gone, as I’m often inclined, into the bathroom/cinema foyer/nearby café to scrawl my thoughts on the back of an envelope or to thumb them into my phone – there might have been some doodling, perhaps, but unlikely many words.

It’s often impossible to identify precisely why we like something – a person, a book, or in this case, a film. Invariably, it’s an odd concoction of time and place and mood and something unfolding that strokes a pleasure receptor or two. (Not to mention the lack of nearby loud-talkers offering up bad quality narration, which, I suspect ruined Truth a little for me).

Looking over my 2015 best/worst list, a clear pattern emerges: I write far more articles about those films I hated than those I liked. In fact, if I look across my entire catalogue of musings, this pattern is sustained: I write about things that bored me or angered me or revolted me far more often than anything I found delightful.

Part of the explanation is simple: there’s just a lot more to say about bad stuff. Bad people, bad student essays, bad travel experiences, bad cinema. It’s easier – and often far more entertaining – to mock, to poke fun, to roll one’s eyes and to catalogue all that went so horribly wrong.

I’m still, for example, getting much mileage out of recalling my favourite bits of celluloid abomination from Saving Christmas. I’d be far less likely, however, to regale my friends with details of the bucket of tears I shed watching an academic developing Alzheimer’s in Still Alice.

But dissecting our love or lust for something is much more difficult. There’s the possibility of overthinking it and draining the joy. Equally, there’s the more taxing bit about having to really think about our desires, to acknowledge our often trivial or treacly yens and to admit that maybe we’re as much a sentimental sucker as the next person.

The razzies

Criticised as anachronistic and snarky, the Razzies – founded in my birth year, 1980 – recognises the very worst in film.

Admittedly, there’s a strong inclination to dismiss the whole thing as a bit mean-spirited. Akin to worst dressed lists or stars-without-make-up exposés, the focus on weakness sits a bit uncomfortably with me. Lashings of time and money and spirit went into a production: is it not kinda awful of us to just sit there and dub something the worst of the worst? Similarly, what criteria are we using? Is a film worse because bazillions of dollars went into it rather than just some wretched backyard straight-to-video nonsense? Is it worse because an actor loquaciously revered just phoned in a lacklustre performance?

A friend took umbrage, for example, with my inclusion of Hot Tub Time Machine 2 in my 2015 worst list. Apparently she saw its inclusion as too easy; as low-hanging fruit. Not a totally ridiculous claim, of course. Anything Adam Sandler touches for example, is an effortless candidate for a Razzie; ditto film sequels.

I really did think Hot Tub Time Machine 2 was rubbish but it’s worth questioning whether it could have ever been anything else. Were my expectations, therefore, really shattered? Did I really go in thinking that the lads getting back in the tub might just change my life?

Equally, did anyone really think that The Ridiculous 6 might just try to initiate a serious awards-season duel with The Hateful Eight?

Surely we don’t believe that all cinema is trying to make grand artistic statements.

Surely we don’t believe that all cinema is trying to teach or transform.

Surely we don’t believe that all cinema is beyond reproach.

If then, we think of cinema not as art, not as a creative vision that may have stumbled, but rather as a cash cow that was cynically hurled at audiences for profit, is it then not up for criticism?

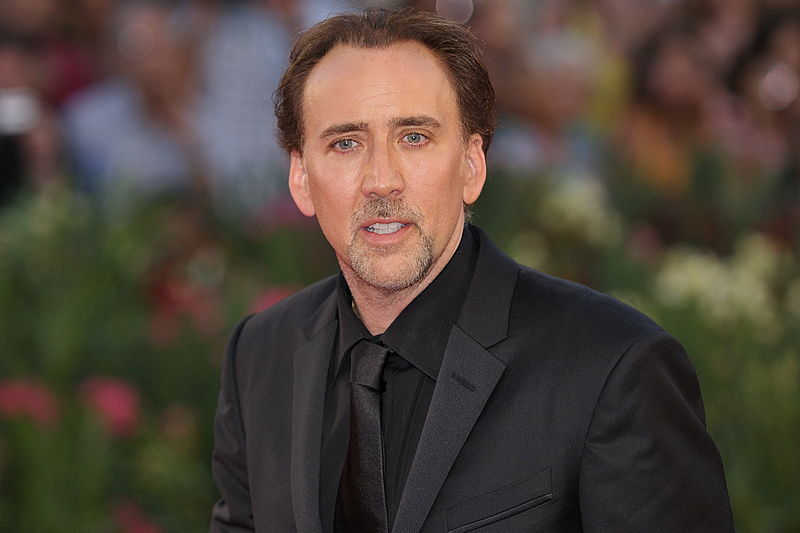

If a film is viewed akin to any other product, why shouldn’t we evaluate it? Why shouldn’t we mock and malign and swear off ever paying to see another Nicolas Cage film again based upon past performance?

Why can’t we want for better films, just as my grandma has devoted the past several decades to buying and returning toasters in an effort to find burnt bread nirvana?

If I’m going to make an annual best list and equally divulge my worst, then it would be hypocritical of me to condemn the Razzies.

We only have the opportunity to talk about the best in cinema, to point to amazing performances and superb cinematography when, on the flipside, we get to compare it to what else is out there; to also spotlight the turkeys. I’m not sure, therefore, if I care too much if the worst is given a gong.

Banner Image: Shutterstock