Bardcore: Why Shakespeare went X-rated

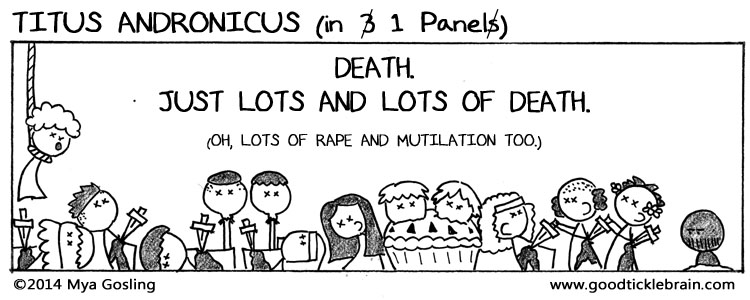

Titus Andronicus was the American Psycho of its day, a bloody, nightmarish vision of a play

Published 20 June 2016

Was Titus Andronicus the American Psycho of its day?

Forget any ideas you might have of ‘gentle Shakespeare’ (as Ben Jonson once described him). Titus Andronicus is a shlock-horror nightmare vision of a play.

Titus returns to Rome after defeating the Goths in battle and, to appease the gods, orders the sacrifice of Alarbus, the son of Tamora, Queen of the Goths.

Seeking revenge on Titus, two of Tamora’s other sons, Chiron and Demetrius, gang rape Titus’s daughter Lavinia and kill her husband. To prevent her disclosing their identities, they cut out her tongue. Apparently not satisfied with this measure, they proceed to cut off her hands to prevent her writing their names.

Further mutilations and decapitations ensue, and in the climactic act of retaliation, Titus kills Tamora’s rapist sons, dismembers the bodies, bakes them in a pie and feeds them to her. Possibly because he knows that no one is leaving the banquet alive, Titus kills his own daughter Lavinia, then Tamora. The emperor kills Titus but is in turn killed by one of Titus’s sons.

Patrick Bateman would be proud. Lovers of ‘gentle Shakespeare’ might not be so fond of the senseless gore, sexual violence, and sick humour.

One reason for Shakespeare’s enduring popularity, though, is his versatility. Not everything he wrote was beautiful, philosophical, or even simply pleasant. Shakespeare was a commercial playwright, attempting to attract paying audiences. Each of the theatres in which his plays were performed was situated in the seedy outskirts of the city.

The Globe theatre was close to bear-baiting and bull-fighting arenas: blood sports as a form of entertainment competed with plays. In the case of Titus Andronicus, we have a literal fork in the road: does the Elizabethan playgoer pay to watch violence, or aestheticised violence?

The play was never banned or censored in Shakespeare’s day. All publicly performed drama was vetted by the Master of the Revels, but censorship was typically motivated by blasphemy or libel, not for gratuitous violence or sex. (There was, of course, no female nudity on stage as there were no female actors). In fact, Titus seems to have been relatively popular. It was published in 1594 (very early for Shakespeare), but only a single copy survives – presumably the hundreds of other copies were literally read to pieces, because a second edition was printed in 1600, another in 1611, and the play included in the First Folio of 1623.

As well as numerous public performances around London, the play was performed privately in 1596 at the Manor House of Sir John Harrington (inventor of the flushing toilet – possibly why it’s sometimes called ‘the John’), and the essence of one performance seems to have been captured by Henry Peacham in the only known contemporary illustration of a Shakespeare play. This all makes it hard to dismiss the play as unpopular or unworthy of a successful playwright like Shakespeare.

However, the play didn’t get much airing between the late 17th century and the mid-20th century. The Victorians, famous for their conservative morals, were in no hurry to recuperate the play. When Ira Aldridge, the black actor famous for his portrayal of Othello, sought to introduce another black role to his repertoire by playing Aaron the Moor, drastic rewriting of Shakespeare’s Titus was required.

The text of Aldridge’s 1850 adaptation is lost, but its point was to elevate Aldridge’s own role (Aaron) and to make the play otherwise palatable to its Victorian audience. A review from The Era notes that, “the deflowerment of Lavinia, cutting out her tongue, chopping off her hands, and the numerous decapitations which occur in the original, are wholly omitted, and the play not only presentable but actually attractive as a result”. The Victorians could tolerate a black actor, but not sexual violence on stage.

Red streamers for blood

Although it was still possible to read Shakespeare’s original play, early critics didn’t want to believe that Shakespeare wrote Titus. (George Peele is now generally credited with writing at least scenes 1, 2, and 6). T. S. Eliot famously complained it is “one of the stupidest and most uninspired plays ever written, a play in which it is incredible that Shakespeare had any hand at all”.

By 1916, the Royal Shakespeare Company had performed all of Shakespeare’s plays except Titus Andronicus, which it would not play for another 39 years. The eventual performance was Peter Brook’s landmark production of 1955, which stylised the violence by using red streamers for blood.

The recently deceased Japanese director, Yukio Ninagawa, used this device to great effect in his 2006 production of the play at RSC. In an interview, Ninagawa advised that “(t)he air of my production may be completely different from a horror film ... But I warn you: it is so beautiful, it will be painful to look at”.

In 1999, the American director Julie Taymor cannily cast Anthony Hopkins (famous at the time for his Hannibal Lector role in particular) as Shakespeare’s orchestrator of cannibalistic violence. Her cinematic adaptation, Titus, is a wonderfully anachronistic blurring of historical periods and styles, evoking Ancient Rome, Mussolini’s Italy and contemporary Hollywood’s fascination with violence-as-entertainment. Archaic armour, tanks and video games blend into one as the film explores this dark undercurrent in human behaviour.

An innovative framing device was introduced: the viewer is encouraged to align their point of view with the character of a little boy (Young Lucius) who is witness to and inheritor of the cycle of violence perpetuated in Shakespeare’s play. Although it certainly contained moments of black humour (the pies of human flesh cooling on a homely domestic window sill), the framing device enables Taymor to treat Titus seriously, as a meditation on the disturbing normalisation of violence in society.

Using a film to dissect film violence makes a lot of sense, but where does that leave theatre practitioners who want to stage Titus Andronicus? Despite what Homer Simpson thinks, live plays can be shocking and viscerally affective.

When Lucy Bailey directed the play at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London in 2006 (reprised 2014), she expressed a concern in her programme notes that “Our world is reverting to the currency of violence that Shakespeare depicts. It is very frightening”.

The Globe production soon became notorious for its graphically realistic violence. “We have had a higher level of fainters this year than we normally would experience,” the Globe advised; it quickly became apparent that first aid officers with stretchers and wheelchairs would be required at every performance to cater to the dozen or so fainters each performance produced.

Bailey deliberately sought to produce not just “stage violence”, but “blood that would spurt and jump”, horrifying the audience. As a reviewer for The Telegraph noted, “there is something about the horrors happening to flesh-and-blood actors that makes theatrical violence particularly effective”. Audiences attending Bailey’s production might be forgiven for thinking they’d stepped back in time further than Shakespeare’s Globe, to the Roman Coliseum, the ultimate theatre of cruelty.

The play has had to overcome a number of obstacles to be accepted alongside its Shakespearean siblings.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Titus has largely overcome the stigma of inferiority or barbarity that plagued it for centuries after its original successes. Partly this is because of the energising effect of Taymor’s film and the revitalised theatrical performances (including Bailey’s) that have garnered so much attention for the play.

Partly it stems from a yearning to explore the Shakespeare canon beyond the classics such as Hamlet and Macbeth, and a curiosity about what the young Shakespeare thought made for good tragedy. But partly, too, it’s the lamentable fact that after the genocides of Rwanda and Yugoslavia, the tragedy of September 11, and the widespread fear of terrorism and random violence, Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus is once more poised to speak directly to the concerns of a playgoing audience.

But are we accepting of the play only because Shakespeare’s name is attached to it? What would happen if, instead of Shakespeare having written it four centuries ago, Bret Easton Ellis produced a novel on this topic today? Would it be in a plastic wrapper? Would it be pulp fiction, condemned for its graphic sexual violence?

Banner image: Pixabay