Arts & Culture

Jon Cattapan, artist, on his Melbourne art tram

Patricia Piccinini’s work is specific and universal, enticing and discomforting, recognisable and elusive – what are the driving forces behind her art?

Published 31 March 2017

Children, maybe 20 of them, are sitting on the dark polished floor at Tolarno Galleries in central Melbourne. I’d put them at eight years old, maybe nine. As the father of an eight-year-old boy, I find their intense air of concentration almost eerie. Some sit with their arms crossed; others lean elbows on their knees; heads are forward, eyes alert. They’re gathered around Teenage Metamorphosis, a 2016 work by Patricia Piccinini in which a human-non-human hybrid lies on a rug, looking plaintive, a copy of Kafka’s Metamorphosis by his head.

The figure’s constituent materials – silicone, fiberglass, human hair, found objects – might not sound very lifelike, but the dewy-eyed end-product most certainly is. Piccinini kneels on the floor, facing the children, and asks if any of them know what organ transplants are. Hands shoot up in in the way they might if she’d just offered a free deck of Pokémon cards.

From there, she talks to them about a human-pig hybrid embryo created recently in the US – again their attention is unbroken. Next comes face transplants, then baby giraffes, then Surrealism. They get up, sit down in front of another Piccinini work, Unfurled (2017), a hyper-realistic sculpture of a glassy-eyed girl on a chair, hands together on her lap, with a magnificent owl perched on her shoulder. As before, the diminutive audience is rapt.

Looking through the catalogue of Piccinini’s work while I wait, it strikes me that children feature regularly – more so than I’d previously noticed. Half an hour later, when the school group leaves, I ask her why that is. “There are lots of reasons,” she says. “In my work I’m speaking about a world that is their world, not ours. As adults, we’re on our way out. “But also, if you look at the girl in a work like Unfurled, you’ll notice she has a kind of spiritual fortitude that’s missing in our media – we don’t ever get to see girls like that.” Piccinini’s work, of course, is instantly recognisable and internationally feted both for its execution and the themes it conjures: bio-technical intervention in the human form, the growth and mutability of human organs and tissue, our planet, evolution. Whether taken as a whole or individually, it can’t help but raise scientific, ethical and philosophical questions.

Arts & Culture

Jon Cattapan, artist, on his Melbourne art tram

She has been creating art steadily since graduating from the Victorian College of the Arts in 1992.

“My themes were present from the very initial moments, even at the VCA,” she says. “I’ve just had the privilege of being able to refine not just the process but also the ideas. That said, I don’t think I could have made my current work straight out of art school.”

Due to the technical challenges? Or in terms of your thinking? “Both. I hadn’t had children then, so my values were different, and the sorts of values that I’m interested in now are a lot more universal. I’m very interested in the environment, and what we constitute as natural.

“Maybe that’s becoming more vital to me since having children, because they’ll have to live with this environment and what we’ve done to it.

“What is our relationship to nature? How does it need to change? My work is about asking those types of questions. Although I don’t actually have the answers.” But her work does elicit plenty of responses. With large-scale publicly-engaged projects such as Skywhale – a gigantic, teat-laden, benevolent-looking hot-air marine creature Piccinini was commissioned to make for Canberra’s centenary celebrations in 2013 – plenty of people did, and continue to, get back to her.

Since its Canberra unveiling, Skywhale has become a regular trope in political cartoons; it was described by the ACT opposition leader Jeremy Hanson as “an embarrassing indulgence only a fourth term government would contemplate”. Did Piccinini feel nervous in the run-up to its public reveal? “No, I was really comfortable,” she says. “No-one made money out of Skywhale. It cost $170,000 but, you know what, that’s what it costs to run the lights on a one-day cricket match – it’s nothing really.

“I just thought ‘everyone’s going to love her’, because she’s so interesting’.”

People began sending Piccinini Skywhale-inspired work. “And not just drawings,” she says. “They made Skywhale bread, cakes, costumes, Lego, stickers, T-shirts, hats – it just went on and on ...”

The 34-by-23-metre balloon was stitched together in the UK by Cameron Balloons. Before its Canberra unveiling, Piccinini and a pilot took it on a test flight over the Grampians in Victoria. What did that feel like? “It was terrifying,” she says. “She’s not the standard tear-shaped balloon, so she moves from side to side in the air. We went up, across this mountain, and she started tipping left and right and, you know, there are no seat belts in a balloon – I felt so scared. “But, it was also incredibly exhilarating, to be up there in the sky, to be really a part of this artwork that began life as a concept drawing.” Skywhale has since flown in Japan, Brazil and Ireland. It was nearly granted entry to the United States, but not quite. Was that because of Trump’s much-maligned travel ban? “Oh no, although she is definitely an ‘alien’. It turns out they have unusually strict laws about balloons there as well. We could get insurance here in Australia, and pretty much anywhere else in the world, but not there.”

My own first contact with Piccinini’s work in situ was at the 2014 Melbourne Now exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria. As just one of more than 175 individual and group presentations, Piccinini’s The Carrier (2012) – a naked, bear-like creature carrying a florally-dressed, barefoot woman on its back – stood out a mile.

It stopped me in my tracks because both creatures looked as if they could conceivably be breathing. I was repulsed, but I was also attracted. I edged closer, part fearing the figures would spring to life, part fearing they wouldn’t. As other people approached the work those same competing instincts seemed to be the norm.

“Yes, that’s really important, and intentional,” says Piccinini. “I could make a work that’s really repulsive, but I think that doesn’t give the viewer enough credit. My work treads that really fine line between push and pull.

“What happens, hopefully, as you get pulled in and pushed away, is that a space opens up where you’re not quite sure what to think. And then you’re left wondering, ‘In fact, what do I think?’ It’s kind of empowering actually.” Elements that trigger thoughts about disability and deformity are threaded through much of Piccinini’s work.

“And because those things aren’t seen as ‘normal’, they’re often seen as being too much, you might feel you can’t go there mentally, that you don’t want to see it. And those types of responses are becoming more widespread because the media around us allows no space for physical difference.

“For me, they are all beautiful. I don’t see their difference as anything but wonderful.” Piccinini has recently returned to the VCA as an Enterprise Professor, a coup for the college as it celebrates 150 years of art in Melbourne. She has plans for what she’ll do with her time there but – other than revealing she’ll be supervising the work of postgraduate students – is keen to keep her powder dry.

Arts & Culture

Animation in the 80s: the view from Melbourne

Back in 1989, she says, she wanted to study at the VCA because “it seemed the best school in Australia”. In hindsight it seems like a marriage made in heaven, but she “actually didn’t get in. Someone dropped out, so they called me halfway through semester, I must’ve been still on the list somewhere.

“I was really pleased to go because Peter Booth had been teaching there, and I liked his work. “It was the 80s, the whole anti-nuclear era, and Peter’s work was quite dystopic. But it wasn’t nihilist. He didn’t advocate destruction – he just showed destruction, and catastrophes, and fire everywhere.

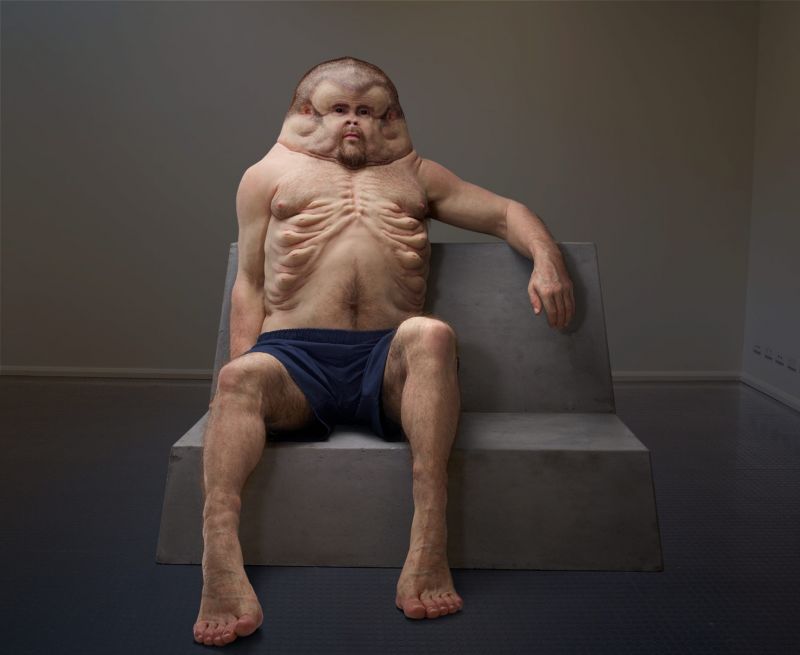

“Sadly, he’d left the VCA by the time I got there but I still had a good experience.” After graduating in 1992, Piccinini took up premises with other recently-graduated artists, in what became known as the Basement Project, an artist-run space on Melbourne’s Collins Street. “There were 12 of us, ten from the VCA,” she recalls. “That time, the early 90s, was a recession and galleries were closing down. But rents were cheap. No-one else wanted the space we found for our gallery, so they gave it to us for $189 a week.” The public spirit driving Piccinini’s work resulted last year in worldwide interest for a sculpture she made for the Transport Accident Commission. Graham, an amalgam of silicon, fiberglass, concrete and human hair, was designed to show what kind of body drivers would need to have in order to survive low-impact car crashes. No neck, a radically-altered torso, a flat face, a thick, spongey skull, hoof-like legs with spring-loaded joints – Graham is recognisably human, scarily so, but he’s also unlike anyone you’re likely to meet.

He became a social-media phenomenon, stealing headlines globally. Meet Graham – a website with an interactive version of the sculpture – got more than 10 million page views in its first week. Piccinini worked with Royal Melbourne Hospital trauma surgeon Christian Kenfield and Monash University Accident Research Centre crash investigation expert Dr David Logan to conceptualise the sculpture – and says she didn’t think twice about accepting the commission. “I did it because it has really great cultural value,” she says. “My cousin died on the road when she was 19. This artwork is the vehicle for a set of ideas.” The fact the project wasn’t didactic also appealed. Shock and awe-style safety campaigns, she says, have the effect of numbing us. “With Graham, you slowly come to understand that, if you want to survive a crash, you need to have a body like his,” she says. “And then, maybe, you get around to the idea that you don’t have one. He’s not just shocking the hell out of you.”

“In a crash, one problem is that your heart separates from the artery, and you bleed out. In other circumstances you can walk away, but drop dead in half an hour. You may not even bleed from your face, but your brain comes forward so quickly that it gets completely scrambled.” “Oh,” I say. “Yeah. Yeah, right.”

Already, at two different points in the interview, I’ve had to raise my hand to remind Piccinini that I’m squeamish. Talk of scrambled brains makes it three – but I appreciate that I’m seeing the world differently as a result of Piccinini’s art. Graham, of course, is no aberration – he’s consistent with Piccinini’s practice and the levers it so effectively pulls. “I’m always very aware of the audience,” she says. “My work isn’t about my personal relationships with people, it’s not my therapy. It’s about stuff that really affects us ethically – and the realisation that those ethics are always changing.”

Banner Image: Artist supplied

This article first appeared in the University of Melbourne’s Victorian College of the Arts and the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music’s ART150 website