Boom town busts affordability

Australia’s long boom in property prices has run into an affordability crisis raising urgent policy questions in an election year.

Published 24 March 2016

In the second episode of The University of Melbourne’s monthly podcast series The Policy Shop, Vice Chancellor Professor Glyn Davis explores issues such as affordability and negative gearing with University of Sydney housing economics expert Dr Judith Yates and University of Melbourne economist Professor John Freebairn. The episode is available for download on iTunes or to stream on the Policy Shop channel here on Pursuit. Here, we set the scene.

By Andrew Trounson

Rachael Newton felt she had no option but to leave her house and business when her relationship with her partner broke down, but it left her swapping one nightmare for another – Australia’s increasingly unaffordable housing market.

Ms Newton spent nearly two years with her teenage daughter battling the shortage of social housing in Victoria, alternating between halfway houses, motels and relatives.

“When you are unemployed, you don’t have a rental history and you are a single parent no one is willing to give you that chance,” says Ms Newton.

Even when she got herself work as a cleaner it didn’t help. She couldn’t compete in a crowded private rental market, and what available social housing there was went to the truly destitute. It was only through HomeGround Real Estate, a social enterprise of Launch Housing that connects those in need with landlords willing to take heavily discounted rents, that she eventually found a place. “Why does it have to be so hard?” she asks.

Ms Newton is at the sharp end of what many say is a housing affordability crisis. The crisis is hitting not just those on low incomes, but also increasingly people on average incomes just trying to buy or even rent a house near a city centre where their jobs are. It has prompted a Senate inquiry, raised fears that we are facing a housing bubble set to burst, and sparked an election-year political fight over whether coveted tax incentives for home owners are part of the problem.

House affordability and affordable housing

For Professor Guay Lim, an economist at the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research at University of Melbourne, the clearest signal we have a problem in housing is that the growth in property prices is far outpacing income growth.

In the mid-1990s city house prices were typically 2.5 times household disposable income, and 3.2 times in Sydney. That gap has doubled with prices now approaching 5 times income, and about 6 times in Sydney. That makes economists worry that the property market is out of line with market fundamentals. It means the market is potentially at risk of becoming an asset bubble. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics the value of Australia’s residential dwellings has risen by 16 per cent from $4.4 billion in 2011 to $5.2 billion by 2014 while inflation has been running at around just 2 per cent.

“As an economist the affordability measure is a key headline number,” says Professor Lim.

A separate but related measure is how many households are in housing stress, not just buyers but especially renters. According to University of Melbourne urban planning expert Professor Carolyn Whitzman, people are generally believed to be in housing stress when they are having to spend more than 30 per cent of their income on paying the rent or the mortgage. And she says more of us are coming under stress.

For example, among renters who are earning about 80 per cent of median income, the proportion under stress has gone up from 20 per cent in the mid-1980s to 40 per cent. As Professor Whitzman says:

What is happening is that the middle income earners – your child care workers, your nurses and your teachers – are getting priced right out of the central city.

And as people are forced to seek housing further and further out they face rising transportation costs in order to access work and services, she says.

For low-income earners a chronic shortage of social housing means they are forced into an expensive and competitive rental market. And at the sharpest end homelessness is rising. Between 2011-12 and 2014-15 the number of people accessing specialist homelessness services rose by over 8 per cent to 256,000, according to Homelessness Australia. Of these some 21 per cent said the main reason for needing assistance was a “housing crisis” such as an eviction or being in arrears on rent or the mortgage. Some 12 per cent gave financial difficulties as the main reason for their situation.

“There is a growing understanding that the critical shortage of new affordable rental properties is unique to Australia and we need to tackle it,” Professor Whitzman says.

Bubble bubble toil and trouble: what’s driving house prices

Professor Lim and colleague Dr Sarantis Tsiaplias have examined the key fundamental factors that drive housing affordability – population growth, unemployment and interest rates. They found that by far the biggest influence in the boom in property prices has been low interest rates. And that raises concern that much of the housing price increase has been fuelled by cheap credit.

And we’ve never been in so much debt. According to a December report by NATSEM and AMP, since 1988 average household debt in Australia has increased four fold after adjustments for inflation, rising from $60,000 to now $245,000.

“When interest rates are sufficiently low, sharp price increases don’t appear to be directly related to factors such as demographic or unemployment conditions,” Professor Lim and Dr Tsiaplias wrote in a report published earlier this year.

The boom in house prices has coincided with the cash rate falling to record low of just 2 per cent as central banks around the world have sought to promote economic growth following the Global Financial Crisis. Indeed, their analysis suggests that demand for borrowing and house buying is stimulated once mortgage rates fall below a threshold rate of about 6 per cent. Current mortgage rates are ranging from 5.90 per cent to 4.45 per cent according to the Reserve Bank, but there are some discounted offers being advertised below 4 per cent. Professor Lim and Dr Tsiaplias warn that:

When the mortgage rate falls below the threshold, investor activity increases dramatically, resulting in price feedbacks that statistically appear as explosive processes in the house price.

“We hear stories of people buying houses for speculative reasons, and that could be problematic for housing affordability because speculative activity increases the risk of booms and busts,” Professor Lim says.

A jittery stock market in the wake of doubts over China’s economic growth can be expected to further stoke property investment.

“A lot of people have the mistaken impression that house prices go up inevitably and infinitely. But there is no such thing as a market that doesn’t have a bust,” says Professor Whitzman.

Home sweet investment

Home ownership in Australia is widespread at just under 70 per cent, and it has been like that since the late 1960s. But Professor Whitzman says that increasingly houses have come to be less a source of shelter and more an investment. This has been encouraged by government tax policy that encourages home ownership and stimulates investment in housing. Australian homes are exempt from Capital Gains Tax, and if you buy a property and the rent doesn’t cover the interest costs you can offset the loss on your taxable income as negative gearing.

But the worry is that such incentives maybe stoking prices. There are concerns the system is encouraging property owners to purchase multiple properties by borrowing against the rising equity in their houses, and along the way locking out those trying to get into the market.

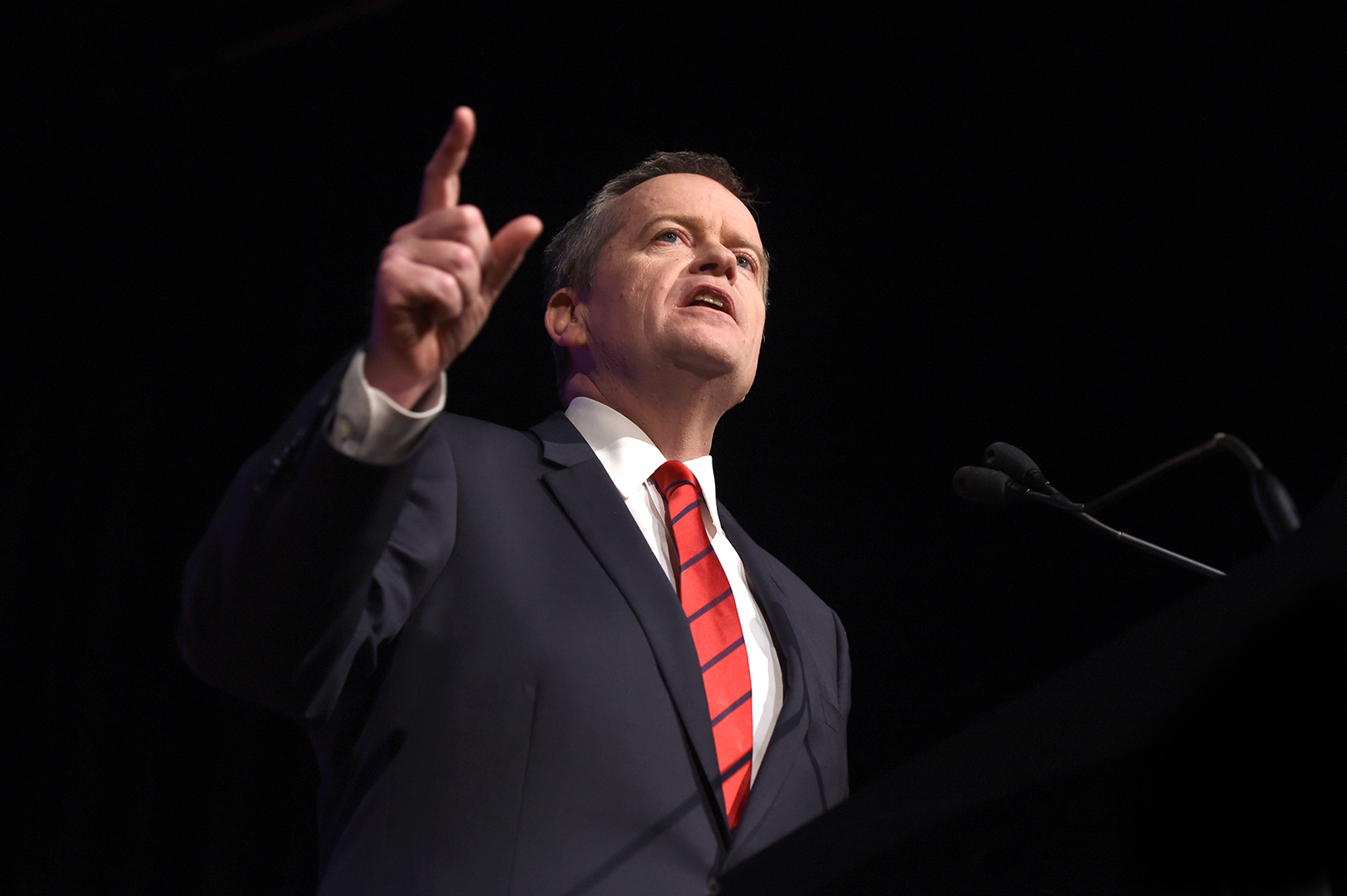

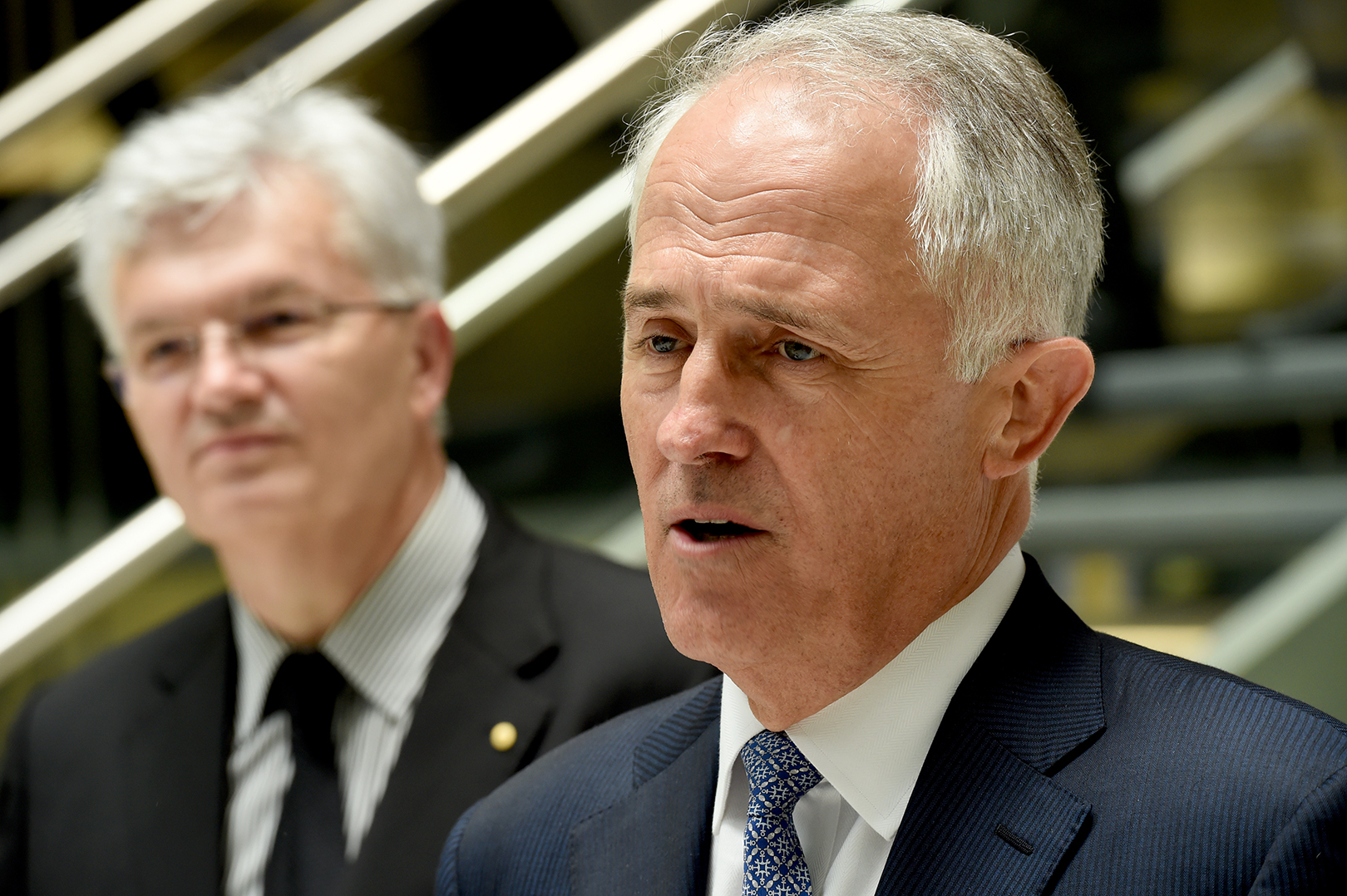

The Labor opposition has put the issue in the policy spotlight by proposing to limit the negative gearing concession to new housing to better target it at encouraging supply. The government has slammed the idea, warning it will hurt established house prices and the extensive household savings tied up in housing, while making the market for new dwellings more expensive. But Treasurer Scott Morrison has also talked of targeting the “excesses” of negative gearing and there is talk of capping claims.

Professor Lim said the extent to which tax incentives may be driving speculative investment in property should be reviewed. But she warns that adjusting tax incentives isn’t simple and proposals to modify negative gearing need to be properly thought through and modelled. She and her colleagues are working on that now.

Policy binds

But unwinding such incentives, even if it were to make sense to do so, could be a fraught exercise. Given the idea of home ownership as a store of value is so widely entrenched, anything that would threaten that value risks alienating significant parts of the electorate. Housing is the single largest asset held by households, making up just over 50 per cent of total household assets.

And if the housing market is reaching bubble proportions, policy makers will be wary of any moves that would cause a crash rather than what economists call a soft landing.

There is also little scope for the Reserve Bank to raise interest rates to engineer just such a soft landing given the sluggish economy.

“The RBA pays attention to asset prices, but monetary policy is about more than managing house prices,” says Professor Lim.

One solution is to boost supply, but that would require heavy investment in accompanying infrastructure like public transport in what is a tight budgetary environment. And without any plan to develop satellite cities, any rapid expansion in supply would also have to be on the ever-growing fringes of our existing major cities, taking people further away from where their jobs are.

The policy ideas

There is no shortage of policy ideas being put forward to address housing affordability. They include boosting spending in social housing and ideas to improve the security of renting to make it a more attractive alternative to buying a house. There are also proposals to replace a property transaction tax like stamp duty with a simple property tax that could reduce prices and encourage under-used housing to be sold.

There are also proposals to encourage more private investment into social housing. Professor Whitzman notes that in the US investors are offered tax breaks to invest in social housing, while in Canada, British Columbia province guarantees mortgages for community housing organisations. According to Professor Whitzman:

There are some easy initiatives governments could do tomorrow that don’t involve direct investment but which can build investor confidence.

The key however is for such policies to be long term. But she notes that long-term policy is difficult when housing policy is politicised and successive governments regularly ditch each other’s long-term infrastructure plans.

“There is a constant politicisation in Australia of urban policy that creates a situation where it is very hard to make tough but essential choices on infrastructure,” Professor Whitzman says.

Filling the vacuum

In the meantime the policy vacuum is being filled by non-government social enterprises like HomeGround Real Estate.

“We need a much bigger supply of affordable housing. We need to find a way of pulling private rental into the range of lower income people,” says Launch Housing deputy CEO Dr Heather Holst.

“We just have more and more people wanting assistance and we can’t just keep doing what we have been doing,” says Dr Holst.

The second episode of Policy Shop will be broadcast on iTunes the week beginning April 4.

Banner image: David Shanlbone/Wikipedia