Arts & Culture

Restoring one of the world’s rarest maps

A new approach to restoring parchment has saved a WW1 Book of Remembrance commemorating local fallen soldiers that was badly damaged by fire and water

Published 12 February 2018

Parchment has been used since Medieval times for significant documents, from the Dead Sea Scrolls to Acts of Parliament.

And it is still used today for British Acts of Parliament and Freedoms of UK Cities (and the invitations to Prince William and Kate Middleton’s wedding).

Made from animal skin treated with lime and stretched while it dries, it is durable enough to survive for centuries when dry. But if it gets wet, it’s a different matter; the parchment reverts to a raw animal product that shrinks, distorts and rots rapidly.

Arts & Culture

Restoring one of the world’s rarest maps

Until recently, conservators have accepted wet parchment documents tend to be badly disfigured or lost entirely. Perhaps most famously, up to a quarter of the founding collection of the British Library, the Cotton Library, was lost in a fire in 1731.

But when a wet and fire-damaged Book of Remembrance from World War One, made from parchment, came to the University of Melbourne’s Grimwade Centre recently, we adopted a new approach to save it.

The book is an important hand-written memorial to the mainly Victorian men of the 58th Battalion Australian Imperial Force (AIF), who died, for the most part, by machine gun fire at the Battle of Fromelle.

The 58th Battalion was formed in Egypt in 1916 from Gallipoli veterans and new recruits. They served in many significant battles on the Western Front including Bullecourt and Polygon Wood.

Written on ninety parchment pages with beautifully illuminated initials, this Book of Remembrance is one of many important memorials to fallen soldiers, containing the calligraphic names of 30 officers, 585 Non-Commissioned officers and men of the battalion.

Similar volumes are displayed with great reverence at the Shrine of Remembrance, where families can request to see the page featuring their relative.

This book was on display at the Essendon Historical Society Museum at the Court House in Moonee Ponds, Melbourne, when an electrical fault caused a fire that destroyed the top floor of the building. The book, fire-damaged and wet, was salvaged the following day by former State Member for Essendon, Judy Maddigan, who had originally negotiated its loan (donning a nearby WW1 helmet in the process, as she wasn’t permitted to enter without a hard-hat).

Arts & Culture

Rebuilding cultural heritage after disaster

It was delivered in this state to the Grimwade Centre’s conservation laboratories where we froze it as a form of temporary preservation while a plan could be made to safely dry and repair it.

Records show other parchment books that have been water damaged have all ended up with significantly distorted pages, parchment that had been weakened and distorted due to decay, or pages that were badly stuck together. Separating the pages and drying them individually appeared the only viable option to retain the book in a condition close to its original form.

While freezing the book had arrested any decay and bought additional time, because it had been wet through, then frozen at -21°C, it had become a solid block of ice.

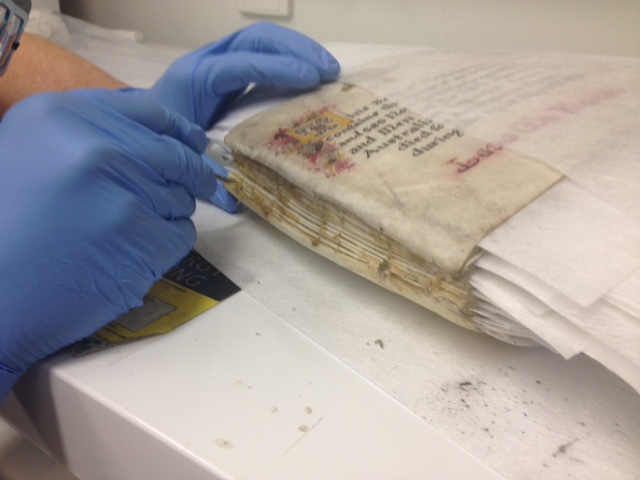

Initially, we separated the pages with a smooth plastic spatula, which took between 60-90 seconds for each page; as the parchment thawed, it became weak and stretchy with a texture similar to uncooked pastry, so we had to work quickly.

The covers, which had been removed while the book was frozen, had also absorbed a lot of water. We scraped them free of a layer of ice before drying them under weights for several weeks, while wrapped in absorbent material that wicked away the water.

With the covers removed, the sewing of the spine was revealed. We cut this carefully with micro-scissors to separate the 15 gatherings, each of six co-joined pages called bi-folios. Each gathering of three bi-folios was individually bagged and frozen so they could be dried separately without thawing the other pages.

While the parchment was still frozen, each gathering was removed from the freezer, scraped free of ice, stretched with clips and secured along all edges. Three people worked rapidly to ensure the parchment was not allowed to distort. This ensured the parchment stayed flat as it contracted while drying.

This painstaking process has been worth it.

We are delighted that, although some staining from the water remains and a couple of pages are burnt at the edges, the names of the soldiers have proven remarkably resilient and are fully intact.

All the pages and covers have been successfully dried and flattened, so the book is now able to be cleaned of soot and reassembled.

Once fully rebound, it will be returned to the 58th Battalion in time for their ANZAC Day celebrations which will see it housed in a new display outside the Mayor’s Chambers in Moonee Valley City Council. It will be displayed alongside the Regimental and Queen’s Colours with all the Battalion Battle Honours, and will be a focal point for public and school tours.

Banner image: Supplied