Arts & Culture

Treasure trove gathered from afar

Modern technology and research restores an ancient Egyptian woman, Meritamun, creating a unique teaching tool for medicine and health science

Published 19 August 2016

Reconstructed from a mummified head dating back at least two millennia, the fine-featured ancient Egyptian face looks out from an artist’s studio in the forested hills of rural Victoria.

Ancient Egypt has fascinated everyone from conquerors like Alexander the Great and Napoleon to movie directors chasing cursed mummies and lost treasures. That same fascination is now driving a unique research and teaching collaboration to test the limits of technology and learn all we can about an ancient Egyptian whose head has been preserved, largely unknown, for almost 100 years at the University of Melbourne.

It is a multi-disciplinary project with the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences that combines medical research, forensic science, computerised tomographic (CT) scanning, 3D printing, Egyptology and art. The team has already produced a reconstruction of the head of an 18 to 25-year-old woman who lived at least 2000 years ago that they named Meritamun, which means beloved of the god Amun. But her serene face is only the start of a journey to answer questions about how she may have died, what diseases she had, when she lived, where she was from, and even what she ate.

“The idea of the project is to take this relic and, in a sense, bring her back to life by using all the new technology,” says Dr Varsha Pilbrow, a biological anthropologist who teaches anatomy at the University’s Department of Anatomy and Neuroscience.

“This way she can become much more than a fascinating object to be put on display. Through her, students will be able to learn how to diagnose pathology marked on our anatomy, and learn how whole population groups can be affected by the environments in which they live.”

How and why the University of Melbourne has a mummified Egyptian head in the basement of its medical building is a mystery. It may well have been part of the collection of Professor Frederic Wood Jones (1879-1954) who before becoming head of anatomy at the University in 1930 had undertaken archaeological survey work in Egypt.

Arts & Culture

Treasure trove gathered from afar

Meritamun is housed in a purpose-built archival container alongside rows of human specimens preserved in glass jars and formaldehyde solution at the Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology, in the School of Biomedical Sciences. She lies face up, as she would have been buried. Even though she is covered in tightly wound bandages and blackened by oil and embalming fluid, her delicate features are clear.

“Her face is kept upright because it is more respectful that way,” says museum curator Dr Ryan Jefferies, who wears plastic gloves as he reverently unties the box to show her. “She was once a living person, just like all the human specimens we have preserved here, and we can’t forget that.”

The genesis of the project was Dr Jefferies’ concern that the head, whose origin remains a mystery, could be decaying from the inside without anyone noticing. Removing the bandages wasn’t an option as it would have damaged the relic and further violated the individual who had been embalmed for the afterlife. But the scan revealed the skull to be in extraordinarily good condition. From there the opportunity to use technology to research the mystery of the head was one that was too good to resist. “The CT scan opened up a whole lot of questions and avenues of enquiry and we realised it was a great forensic and teaching opportunity in collaborative research,” says Dr Jefferies, a parasitologist.

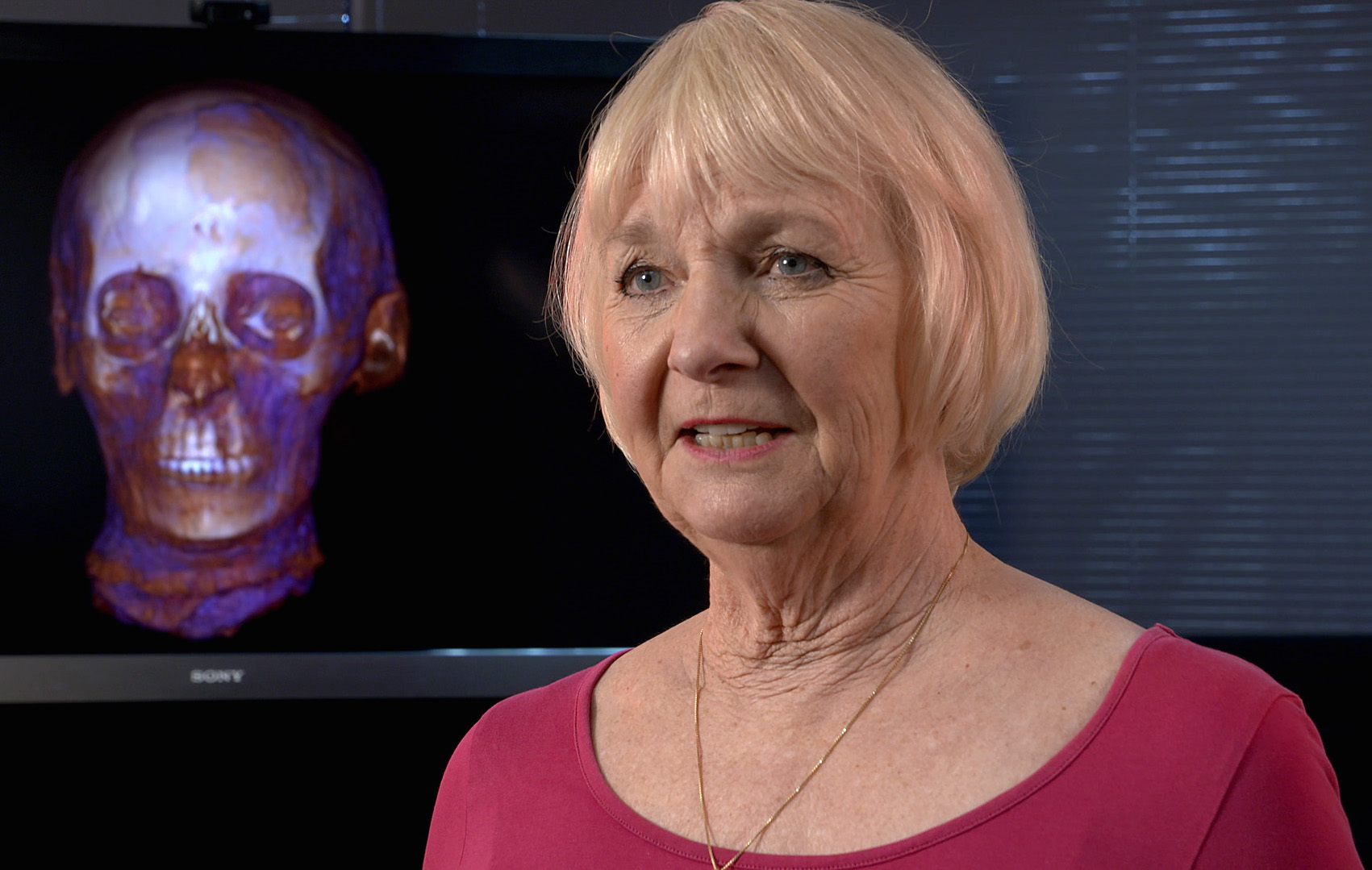

Meritamun was identified as ancient Egyptian by Dr Janet Davey, a forensic Egyptologist from Monash University who is based at the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, where the head was scanned. She jumped at the opportunity to study the head further, and at the Institute she had a wealth of forensic expertise on which to call.

“There are not too many people I know who aren’t interested in Egyptology and the mysteries of ancient Egypt, so when you need to tap into expertise there always seems to be someone prepared to give up their time for you,” says Dr Davey, who habitually wears around her neck a gold pendant of Egyptian Queen Nefertiti.

Dr Davey determined Meritamun’s gender from the bone structure of her face, identifying such markers as the smallness and angle of the jaw, the narrowness of the roof of her mouth, and the roundness of her eye sockets. But to be sure she had her conclusions confirmed by anthropologist Professor Caroline Wilkinson from Liverpool John Moores University in the UK. She is a world expert in facial reconstruction and made headlines when she restored the face of King Richard III, who was killed in battle in 1485.

Dr Davey guesses that Meritamun was probably about 162cm tall, given accepted thinking that ancient peoples were generally shorter than people today. If the researchers had bone from her arm, leg or even just her heel they could have established a more accurate estimate.

Dating her is also difficult. Meritamun has some significant tooth decay that conventional thinking would date her to Greco-Roman times when sugar was introduced after Alexander’s conquest of Egypt in 331BC. But honey could also account for the decay. And while mummification was more accessible to Egyptians after Alexander’s time, the fineness of the linen bandages suggest Meritamun was high status enough anyway to be embalmed at the earlier time of the Pharaohs.

“There is always a lot of mystery to unravel in forensic Egyptology and it is why it is so important to keep an open mind and follow the evidence,” says Dr Davey.

She is now waiting on radiocarbon dating to give a better idea of when Meritamun lived, which Dr Davey says could be as long ago as c1500 BCE. Radiocarbon dating works by measuring the amount of organic carbon atoms that are left in a tissue sample. Since carbon atoms decay over time, the fewer carbon atoms there are in a sample, the older it is.

University of Melbourne biomedical science masters student Stacey Gorski, under the supervision of Dr Pilbrow, is using forensic pathology to try to uncover how healthy Meritamun was and how she may have died.

Just from reading the CT scans Gorski has been able to see that in addition to two tooth abscesses, there are patches on the skull where the bone had pitted and thinned. It is a clear symptom of anaemia, which is a lack of red blood cells that starves the body of oxygen. The thinning occurs when the bone marrow swells as it goes into overdrive in an effort to produce more red blood cells.

In Meritamun’s case, it may have been caused by malaria parasites such as malaria or the flatworm infection schistosomiasis, both of which would have been hazards in the Nile Delta in ancient times. “The fact that she lived to adulthood suggests that she was infected later in life,” says Gorski. Nevertheless, the parasites and anaemia would have left her pale and lethargic at the end.

“Anaemia is a very common pathology that is found in bodies from ancient Egypt, but it usually isn’t very clear to see unless you can look directly at the skull,” says Gorski. “But it was completely clear from just looking at the images.”

Without having the rest of Meritamun’s body it will be impossible to know for sure how she died, but the anaemia could certainly have been a predisposing factor, as could the abscesses if they had become seriously infected.

Gorski is now working to find out what caused the anaemia. One possible way to find out would be to undertake a molecular analysis of a small tissue sample taken from her exposed neck in the hope of finding some DNA evidence of a parasite.

But such DNA analysis, assuming any could be found, is expensive and beyond the project’s budget. Instead, she plans to undertake what is called a “histological” study in which she will rehydrate a small tissue sample and use an electron microscope in the hope of finding evidence of diseases or parasites.

This is a long shot since such evidence is more likely to be found in organ tissue, but it is a chance to test new techniques and it may yet uncover other evidence.

Gorski is even hoping to deduce what Meritamun ate and where in Egypt she may have lived, by studying the carbon and nitrogen atoms present in a tissue sample. Different plants, including vegetables, fruit and grains, all produce different types of carbon and nitrogen atoms, known as isotopes.

By comparing the types of isotopes present Gorski may be able to determine Meritamun’s broad diet. The results could theoretically place her in an area of Egypt that, for example, we know was more dependent on one crop compared to another.

It took 140 hours of printing time on a simple consumer-level 3D printer to produce the skull that has been used to reconstruct Meritamun’s face, not counting the tweaking and design work of the Department of Anatomy and Neuroscience’s imaging technician Gavan Mitchell. Because the 3D printer builds from the bottom up and the print is always more detailed at the top, Mitchell has to print out the skull out in two sections to better capture the detail of the jaws and the base of the skull.

“It has been a hugely rewarding process to be able to transform the skull from CT data on a screen into a tangible thing that can be handled and examined,” says Mitchell, who has a BSc majoring in scientific photography.

Being able to print out body parts and organs is opening a whole new use for the university’s specimen collection. One of the best ways of producing a specimen that can be handled by students is by using plastination, which is a process in which the tissue fluid is replaced with a hard silicon resin. But CT scanning technology combined with 3D printing means that multiple copies of specimens can be reproduced for handling and study, including old rare specimens that display unusual forms of disease or damage.

“We can now replicate specimens with really interesting pathologies for students to handle and for virtual reality environments without ever touching the specimen itself,” Mitchell says.

The printed skull formed the base on which sculptor Jennifer Mann has used all her forensic and artistic skill to reconstruct Meritamun’s face.

“It is incredible that her skull is in such good condition after all this time, and the model that Gavan produced was beautiful in its details,” says Mann.

Mann learned the technique for facial reconstruction at the Forensic Anthropology Centre at Texas State University where she studied with leading forensic sculptor Karen T. Taylor. She practised on skull casts previously used in actual cases to reconstruct unidentified murder victims.

“It is really poignant work and extremely important for finally identifying these people who would otherwise have remained unknown.”

She cautions that any facial reconstruction can only be an approximation of what someone actually looked like in life, but the results she had at Texas closely matched those of the eventually identified murder victims.

The methodology involves attaching to the printed skull plastic markers to indicate different tissue depths at key points on the face, based on averages in population data. This data is derived from modern Egyptians and has been specifically selected by reconstruction experts from around the world as the best approximation for ancient Egyptians.

It was then about applying the clay according to the musculature of the face and known anatomical ratios based on the actual skull. For example, Meritamun’s nose is squashed almost flat by the tight bandaging, but Mann was able to estimate what her nose would have looked like using calculations based on the dimensions of the nasal cavity. The skull also displays a small overbite that Mann has reconstructed. Meritamun’s ears are based on the CT scan results.

“I have followed the evidence and an accepted methodology for reconstruction and out of that has emerged the face of someone who has come down to us from so long ago. It is an amazing feeling.”

The reconstruction was then cast in a polyurethane resin and painted. The researchers have taken a middle course in the long-running debate on what the predominant skin colour of ancient Egyptians may have been, choosing a dark olive hue. The finishing touch was to reconstruct her hair, which has been modelled on that of an Egyptian woman, Lady Rai, who lived around 1570-1530 BCE and whose mummified body is now in the Egypt Museum in Cairo. She wears her hair in tightly-plaited thin braids either side of her head. For the Meritamun reconstruction, replicating Lady Rai’s hair was an all-day job for a Melbourne African hair salon.

For the ancient Egyptians, mummification was about preserving the body so that the dead person’s spirit could find it again and secure everlasting life in the hereafter, while in this life their name could be preserved on their tombs. Tragically for the mummified head at the University of Melbourne, her name was lost long ago, but the researchers feel that by giving her a name and restoring her face they have gone someway to making up for what happened to her.

As Dr Davey says, “by reconstructing her we are giving back some of her identity, and in return she has given this group of diverse researchers a wonderful opportunity to investigate and push the boundaries of knowledge and technology as far as we can go”.

Lauren Greig, CT Business Manager at Siemens Australia and New Zealand, has provided vital support for the project. Dr Janet Davey was assisted by Monash University PhD candidate Samantha Rowbotham. The following have also contributed generously to this research: Dr Chris O’Donnell and Dr Richard Bassett from the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine; Professor Caroline Wilkinson from Liverpool John Moores University; Mary Asamoah from the African Queen Hair Salon; Lora Collins from the Smithsonian Institution; Kristina Scheelen from University of Gottingen; Rodney Broad, Malmsbury; Karen T. Taylor and the Forensic Anthropology Centre, Texas State University; and from University of Melbourne Associate Professor Chris Briggs, Marica Mucic, Holly Jones-Amin, Dr Andrew Jamieson, Dr Louise van der Werff, Ben Loveridge, Dr Rita Hardiman, Dr Ross Jones and Ben Kruenen.

Banner Image: Meritamun. Sculpture: Jennifer Mann. Picture: Paul Burston