By filming in a single shot, Adolescence is choreographed with the precision of live theatre

Each one-hour episode of Netflix’s Adolescence is realised in a single, unbroken take. No edits. No resets.

Published 9 April 2025

Adolescence, a four-part Netflix series, is generating tremendous press not only for the show’s harrowing subject matter, but for the way in which the production was made: each one-hour episode is realised in a single, unbroken take.

No edits. No resets. Just presence.

To achieve this, the creators deployed cutting-edge technology in service of one of cinema’s oldest traditions.

The earliest forms of cinema were actually unedited. The Lumiere brothers’ film La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon made in 1895 and widely believed to be the first motion picture film ever exhibited, depicts a bustling scene in which workers leaving a factory at the end of a day spill out into a yard and onto the street.

The 45-second sequence was recorded on a single length of around 50 feet of film. These early works had a unity of time and space that defined the narrative form.

Adolescence is in many ways a return to that idea – though not entirely.

While many films have experimented with extended takes, it wasn’t until the digital age that hour-long or feature-length productions became feasible in one continuous shot.

One of the earliest examples was Mike Figgis’s Timecode (2000), which plays out over 98 minutes across four simultaneous, continuous takes presented in split screen.

More famously, Alexander Sokurov’s Russian Ark (2002) glides through 300 years of Russian history in one elegant take, filmed in the Hermitage Museum of St Petersburg with a literal cast of thousands.

In traditional screen storytelling – what film theorist David Bordwell terms the ‘classical Hollywood’ style – post-production editing allows the camera to freely jump from wide shots to close-ups and from one time or space to another.

Adolescence resists this in favour of locking you into a real time and real space with the characters. You walk the corridors they walk, witness events as they unfold, and experience tension not through twists, but through proximity and delay.

The ticking clock doesn’t just heighten tension for the characters – it reframes how the audience pays attention. Instead of polishing narrative arcs or delivering tidy resolutions, Adolescence lingers in ambiguity.

The format suits the show’s themes: witnessing, not resolving. It raises questions about how young boys and men are shaped by forces adults can’t always see, let alone stop. The point isn’t to explain. It’s to stay present.

This embodied perspective reshapes the story’s emotional register.

Adolescence writer Jack Thorne has described how the single-take constraint imposed a kind of unity that transformed the writing process:

I’d say the one-shot format does two fundamental things that I find exciting as a writer: the first is that it imposed a structure on the writing. You have the sort of theatrical unities; the unity of time, place, action forced upon you. The second thing it does, and this is the thing that I think transformed the process for me, is it gives the actor the power.

The one-shot restriction becomes a source of invention throughout the entire process.

Scenes were rewritten to better suit the real-time movement of characters through real-world locations. Camera moves like the much-discussed drone shot in episode two emerge as solutions to problems of time and space being inextricably bound.

Arts & Culture

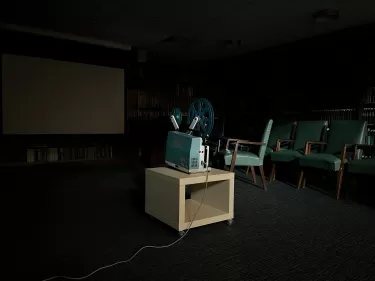

16mm films should be experienced, not just seen

Like in theatre, actors determine and play out the rhythms of performance, requiring a substantial level of focus and stamina.

This demands extraordinary coordination, and each episode is choreographed with the precision of live theatre. There’s no safety net. If something falters at minute 56, the team starts again. Some episodes took over a dozen full-length takes to get right.

The technical execution of Adolescence is staggering. Using DJI Ronin 4D cameras, support vehicles, drones, Steadicams and precisely coordinated choreography, the production team achieved a level of fluidity and control previously unthinkable in a TV production schedule.

The one-shot technique, while removing one artifice, introduces another – it becomes filmmaking as performance.

And that performance relies on a distributed model of leadership. Every department shares responsibility for the outcome. Camera operators dressed as extras to stay invisible on set. Boom operators had to be mobile, reactive and silent. Everyone knew their role – and everyone else’s timing.

You see a swan glide gracefully across the water, but its legs are flapping like mad. And that is basically what each one of these episodes are.Actor Stephen Graham (Eddie Miller)

The effect recalls the high-stakes focus of the film-stock era, when every frame counted. In contrast to the looser rhythms of digital production, Adolescence creates clarity of purpose. Everyone knows where the camera is going; that shared understanding lifts the entire production.

It also reframes editing. While the show appears unedited, much of the work traditionally done in post-production shifts to pre-production and rehearsal.

The ‘edit’ essentially happens before the shoot. Timing, blocking, transitions – all of it is constructed ahead of time, then held live.

Still, Adolescence doesn’t fully escape cinematic convention. Each episode, rather than using a static ‘wide shot’ is instead a single ‘sequence shot’.

Sequence shots, although unedited, essentially mimic the qualities of montage editing by moving the camera around to different positions within scenarios and finding frames that would usually appear in traditionally edited coverage: close-ups of characters, over-the-shoulder shots of conversations, tracking shots that hold characters in profile.

The four sequence shots in Adolescence are designed to create an energetic flow through the work that links frames and allows for shifting character perspectives.

Time, in this style of coverage (as in montage), is ultimately subordinated to action.

So why film in real time if you are essentially recreating a form of montage? At its core, Adolescence is about reality. Not reality as in ‘realism’, but as lived experience – time, discomfort, uncertainty, breath. The form has become part of the show’s identity – and its marketing.

But it’s more than a gimmick. In resisting montage, Adolescence demands more from its viewers. You can’t skip forward. You can’t cut away from discomfort. You’re present whether you want to be or not.

And that’s the point. In a time of fragmented attention and filtered storytelling, Adolescence asks us to stop, stay and witness.

It returns us to cinema’s earliest instincts – of presence, of duration, of simply being there – but fuses those with the most advanced tools we have. It’s a train you can’t get off.

A story you don’t just watch – but endure.