Sciences & Technology

Q&A: How women and girls are changing gaming

Pioneering 95-year-old Australian mathematician and statistician Alison Harcourt AO has made a big impact on her field, and on her colleagues

Published 12 May 2025

Alison Harcourt (nee Doig) is a pioneer in the mathematical field of optimisation.

In 1960, she co-authored a ground-breaking paper that proposed an optimal method to solve complex decision problems where the answers needed to be integer values. This method later became known as ‘branch-and-bound’.

Branch-and-bound underpins modern-day optimisation software packages that provide efficient solutions to problems ranging from logistics and transportation to scheduling, telecommunications and even cancer radiotherapy treatment planning.

Alison wrote the paper while working as a research assistant at the London School of Economics, where she also taught Mick Jagger in one of her classes.

Alison had gone to the LSE after completing a Master’s thesis on integer linear programming at the University of Melbourne in the mid-1950s.

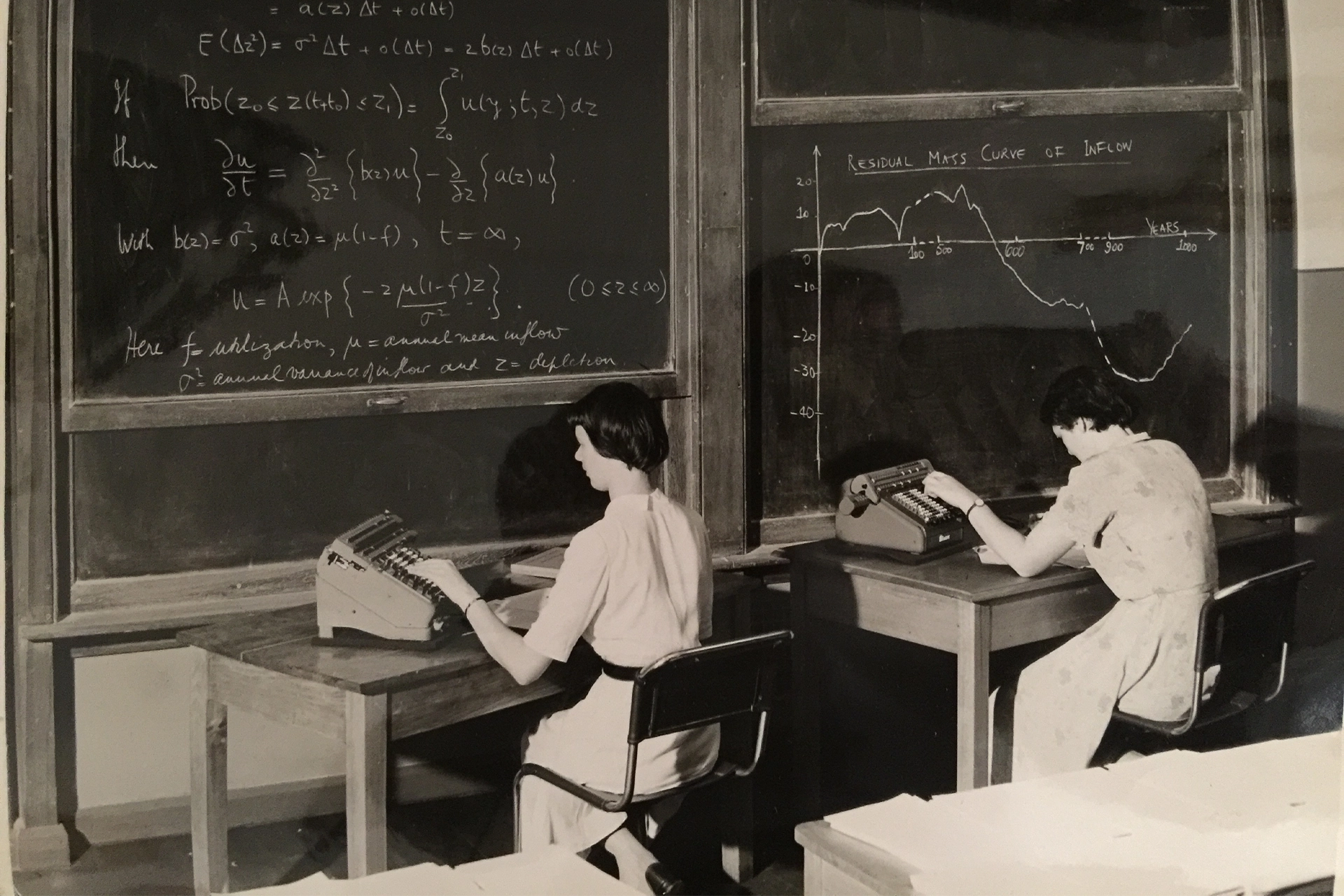

She returned to the University of Melbourne in the 1960s to take up a position as a Senior Lecturer in Statistics. She never enrolled in a PhD and had career interruptions for child-raising in the 1970s and 1980s.

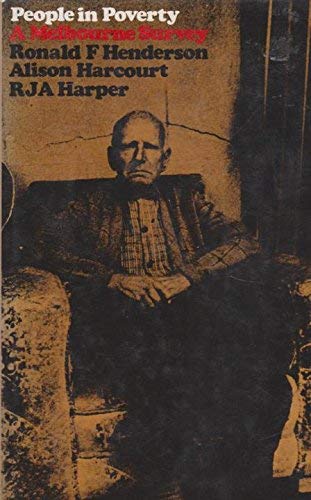

In the late 1960s, Alison worked with Professors Ronald Henderson and John Harper at the University of Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (now the Melbourne Institute) to measure the extent of poverty in Melbourne and to develop an Australian poverty line.

Sciences & Technology

Q&A: How women and girls are changing gaming

This important social research has been cited as the “first systematic attempt to estimate the extent of poverty in Australia”, and formed the basis for the Henderson Inquiry into Poverty launched by the Commonwealth Government in 1972.

The Melbourne Institute continues to publish quarterly updates to the Poverty Line.

In the early 1980s, Alison worked with Dr Malcolm Clark from Monash University to propose a method of double randomisation to allocate candidate positions on ballot papers. This “quirky electoral tradition” is now used as a fundamental aspect of promoting fairness at all Australian elections.

Alison formally retired in 1994 but continues to share her passion for mathematics and statistics. Her pioneering work, especially in establishing the foundations of mathematical optimisation, continues to have major societal impact.

For International Women in Mathematics Day, her colleagues reflect on their experiences of working with Alison and on her legacy.

I first heard of Alison over twenty years ago in Montreal, when my PhD supervisor, Gilbert Laporte, mentioned her famous paper during a class.

The first author of that paper was his own supervisor, Ailsa Land, who was still at the London School of Economics. But he did not know what had become of the second author. “All I know is that she was Australian and that she shares your name,” Gilbert said to me.

Many years later, I started teaching optimisation (and her own branch-and-bound method) at the University of Melbourne. I always mentioned the mystery of this Australian woman who was my namesake and who had disappeared after publishing such an influential paper.

After one of these classes, a student approached me and said, “Professor, there’s a tutor here named Alison. Maybe it’s her.”

With little hope, I looked into it, and to my surprise, the tutor was indeed Alison Doig, now Alison Harcourt. My desire was to run, knock on each one of my colleagues’ doors and ask: “Do you know who that woman is?”.

Sciences & Technology

Heroines of mathematics

I shared the news with Gilbert, who passed it on to his extensive network, and I also invited her to speak at AMSI Optimise 2018, an upcoming optimisation conference which I happened to chair.

The event was picked up by the ABC, which aired an episode about her and helped accelerate the long-overdue recognition of her work.

Later that year, she received an honorary doctorate and was named Senior Victorian of the Year. She was also made an Officer of the Order of Australia in 2019.

For most of her life, Alison went unrecognised. She was even denied the opportunity to continue as a senior lecturer after choosing to have children.

Through it all, however, she never became bitter. On the contrary, she found in her new position as a tutor the venue to express her deep love for teaching, mathematics and her students – an example I find deeply inspiring.

I taught small group classes with Alison over a couple of decades. She loved teaching and strong bonds developed between her and her students.

In teaching she was very empathic and generous, always able to meet students at their point of need. She was meticulous and considered in everything she said and capable of communicating the core concepts from her deep and extensive understanding of the subject matter.

She really cared about her students – she would regularly visit me after the return of final results to go through all the students in her tutorials to see if they went as she anticipated, and had a buzz of excitement when someone who was struggling came through with a good result!

She had an opinion or expectation for every student she worked with – sometimes numbering eighty or more each semester. She came to know all of them as individuals.

And above all she had a great sense of fun – if a problem was boring she would tell staff in no uncertain terms to improve it and she continually offered innovative suggestions of her own on curriculum.

Sciences & Technology

Trailblazing for women in science

She made tough calls on career versus family at a time when the support structures were nowhere near as good as they are today, but managed to succeed in both these avenues of her life.

Her children have inherited her intellect, her compassion, her deep concern for the planet and for people, her political acumen and her basic humility and joyful appreciation of life.

A young researcher from the UK once visited Melbourne to give a talk specifically about the seminal branch-and-bound paper of Doig and Land and how it gave birth to a whole new chapter in optimisation.

She had no idea Alison (the Doig in Doig and Land) was in Australia – let alone in Melbourne.

Alison just rocked up – making no fuss at all, not telegraphing her presence in any way.

At the end of the seminar she approached the speaker – fully 60 years her junior – and quietly said, “I enjoyed your talk very much. I'm Doig.”

Needless to say the researcher was blown away, and I imagine they were still eating and drinking together hours later.

Working with Alison has been one of the joys of my professional life. She is an inspiration.

While I was a mathematics student at the University of Melbourne in the early 1990s, I had no idea that the inventor of the famous branch-and-bound method was down the corridor tutoring statistics, as I was sitting in a lecture theatre learning about her method.

I still have no idea why she wasn’t asked to come and give that lecture.

It wasn’t until I returned to the University many years later that my colleague Alysson Costa told me that the famous Alison Doig (now Alison Harcourt) was one of our tutors and had been in the building for decades.

Alysson was planning a Women in Optimisation panel at AMSI Optimise 2018, which he invited me to chair. He had invited several international women on the panel, and Alison Harcourt!

This was the first opportunity I had to meet with Alison, privately but also to chat with her in front of an audience. I was struck by her humility and wisdom.

Sciences & Technology

Miss Lambert’s Thylacine skull

We organised some media interviews to tell this inspiring story to the general public, and I nominated Alison for an honorary doctorate from our university since her work has had such a profound impact on both mathematics and society.

One of the highlights of my career has been the public lecture I gave jointly with Alison in 2021, called Optimal Decision Making: a tribute to female ingenuity, which allowed me to showcase her work and its influence, and gave Alison the opportunity to share her remarkable story of how a girl from a country town in Victoria came to invent a mathematical technique that would change the world forever.