Challenging times for Australian democracy

Problems abound, but the foundations remain rock solid

Published 25 September 2015

Is there a crisis in Australian democracy? You would be forgiven thinking the answer was obvious following the events of the last few weeks. Australia has now had four prime ministers in six years; their own parties removed three while in office.

At face value, and for a democracy most people assume is tediously stable, these are not good numbers - perhaps even undignified ones.

Donald Horne argued over half a century ago that Australia is culturally derivative and unimaginative but at the same time predictable. We might question the first two observations, but there is a growing sense the last observation no longer holds. The last week in Australian politics just adds fuel to that particular fire.

What is for certain is not all appears healthy in the heart of Australian democracy.

Many groups are marginalised, as a country we have not advanced many issues that are the test of a functioning, inclusive democratic nation. There is a long-standing policy deadlock on the our response to global warming, where we are far from leading, and on our treatment of asylum seekers, where Australia has struggled for answers over the last two decades. The political culture is toxic year-round.

At the same time, on average Australians are better off than they have ever been. Australians are living longer and enjoying a higher standard of living than those in most other nations. Even if many people in Australia loudly complain about imagined hardships, oblivious to the reality, they on average have wealth and health few throughout history could have imagined.

And Australia’s democratic institutions are certainly stable. While in the previous decade, Australia has changed government twice, but has had ten opposition leaders and four Prime Ministers, none of this has resulted in a military coup. Even if the federation is unbalanced, with the vastly uneven split between Commonwealth and State budgets, our schools and hospitals still function well most of the time.

At first glance the state of Australian democracy seems unbalanced at best.

It is hard to get away from the sense Australian democracy might just be getting through, dodging bullet, with the whole edifice to collapse – pick your metaphor.

There is certainly strong case suggesting a deeper problem with democracy the world over. In his book The Confidence Trap: a history of democracy in crisis from World War I to the present, British academic David Runciman highlights a sense of recurring crisis which distinguishes contemporary democracies from other forms of rule. Plagued by short-term thinking, representative democracies persistently plunge towards crisis moments through a failure to deal rationally with the many hard issues they confront.

Is Australian democracy writ large? And how to test?

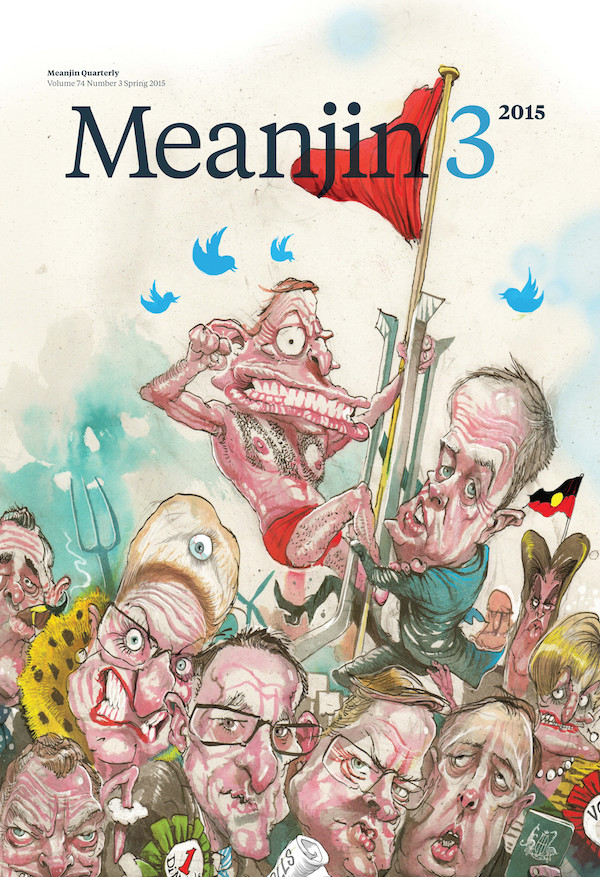

The recently-released Meanjin Spring 2015 focuses on Australian democracy and its discontents. I was co-editor with University of Melbourne Vice-Chancellor Glyn Davis and we asked more than a hundred people to address different aspects of question: is there a crisis in Australian democracy?

Those approached were deliberatively a diverse group, so as to capture as many perspectives as possible.

They included former leaders and legislators on all sides of politics, seasoned policy advocates and practiced commentators. More than half accepted the challenge, from activists to those who contribute to democratic discourse through art, writing and research.

The essays they contributed provide a rich study of this moment in Australian democracy, alongside its past and future. There are contributors concerned with politics, political movements and system design, as well as key policy challenges from reform of federalism and representation of rural constituents, to challenges for marginalised groups and Indigenous Australia. Together they provide insight as to where Australian democracy is at in 2015.

Several authors contend the most vivid examples of the crisis in parliamentary politics and good government are more than just futile readings. As Judith Brett notes, “all bad governments are bad in their own way, letting down different constituencies and betraying different values and traditions”. So it was she contends with the former Abbott government, with a prime minister and treasurer seemingly lacking economic literacy, leading us to ask whether the “Liberal Party is losing its historic identity as the party of good government”.

Other contributors argue while parties and governments can be bad, and often are, they are broad churches and there will be bad eggs. As Meredith Burgmann says, being an ALP member is “sometimes hard going… there are party outliers with terrible views on women, abortion, mining, refugees and so on.”

Several authors propose the state of the parties is as much to do with the rise of the professional politicians as anything. As Clive Palmer puts it “politicians say they care, but most of the time they don’t… they don’t care about you, your family or your future… all they care about is being re-elected.” Which is a blunt message from a member of the House of Representatives.

Contributors explore the deep stasis in Australia’s public response to issues such as the environmental change, where we at times fall badly behind. Our response, as Brendon Gleeson puts it, “is mixed and fractious”.

Contributors also show that Australia’s record on Indigenous issues is also about the swing and roundabouts in the arrangements for public policy making, lacking continuity and exacerbating very difficult challenges. They also show despite significant recent gains, there is a long way to go to achieve equal gender representation in our democratic institutions.

But this is the rub: contributors to the issue see few of these as truly intractable problems, so insurmountable we should give up now.

There are many innovative and elegant solutions for the country to explore.

There are some straightforward but politically difficult reforms Australia could undertake, such as Mark Triffitt’s suggestion of putting caps on election campaign spending. Caps would remove the leverage that economic elites have on the political and policymaking process. Many contributors in the volume also offer more radical solutions, such as deliberative and participative democracy, requiring significant thinking to make workable.

Citizen participation and deliberative democracy can work. As Nick Reece tells us, we need “the revival of one of democracy’s earliest institutions, the citizen jury, to help rebuild trust in political decision-making and help Australia get back its reform mojo.”

There could hardly be a more crucial question than the arrangements by which we govern ourselves and each other, nor a more important challenge if, as Runciman contends, key issues cannot be addressed under the present system.

Democracy is not an end but an evolving practice, a social institution that needs constant examination and regular reform to remain potent. We can revel in its traditions and landmarks, and even question whether democracy remains the best choice for this nation, given much evidence of public apathy. Doug Hendrie even suggests that “Singapore offers us a promising new variant to try: government for the people, without the people.”

But despite all the problems with Australian democracy there is clear agreement we seem to be doing ok.

For Australian democracy maybe Frank Sinatra said it best – regrets, I’ve had a few; But then again, too few to mention. This is what comes through in diverse, provocative, perceptive and, hopefully, enjoyable collection of voices in the latest issue of Meanjin.

Meanjin Spring 2015. Volume 74, Number 3.

Paperback $29.99/eBook $9.99. https://www.mup.com.au/items/162492

Annual Subscription $100. http://meanjin.com.au/subscribe/