In praise of technocracy: Why Australia must imitate Singapore

In this extract from Meanjin Spring 2015 magazine, Doug Hendrie argues the island state offers Australia a promising new variant of government to try out

Published 24 September 2015

In Western thinking, market democracy was, until the great financial crisis (GFC), essentially the end of history. What could better a system that defeated fascism and communism? Not even Asia’s rise seemed to challenge popular rule coupled with competing enterprises. The threat of Japanese economic power failed to eventuate, and China’s long export-driven boom was built on continued Western growth. But the GFC has changed many things. The European Union and the United States are still recovering. In Australia, our seven-year grace period is now over. As growth in China slows, we are suddenly vulnerable.

With the economic challenges comes political uncertainty. The sanguine givens of steady-as-she-goes Australian politics are no more. The public won’t get rid of you in the first term, stated one piece of accepted wisdom. No more. The Liberals were turfed out in Queensland and Victoria after a single term; white ants already riddle Abbott’s government. (Editor’s note: this essay was written before Tony Abbott was deposed as Australian Prime Minister).

Mandatory voting forces voters to take an interest, according to another piece of wisdom. No longer. One in five Australians eligible to vote did not do so in the 2010 election. Even more remarkable was last year’s Lowy Institute poll that found 40 per cent of us no longer believed democracy is the best form of government. The number one reason people gave? Democracy now served vested interests.

But, as is often the case, this popular belief is incorrect. Vested interests don’t dominate our politics. We, the great majority, do. And we want to be rewarded for our support. That’s where the proceeds of the mining boom went: short-term payouts to our families and our businesses. The political classes rely ever more heavily on focus groups to find out precisely what we want—and then parrot these notions back to us. But do we feel heard? Hardly. We feel the process is ever more pointless. On that, at least, we’re right.

The real problem is far broader. It’s not the political elites. It’s us. The informed citizenry on which a functioning democracy relies is no longer possible.

As states lose power and complex cross-border issues gain prominence, we voters are poorly placed to rule via our representatives.

Why so? Well, what limit would you place on asylum seeker intake? Where will you find the budget savings required post-boom? Would you compensate landlords if we phase out negative gearing? Have you got answers? No. Me either. Yet we vote as if we do. Or we favour our private interests. Or rely on emotional reactions to knotty problems.

Our fickle, populist democracy will not cope with this century’s challenges. We inhabit a multipolar world, with ever-increasing flows of undocumented people and hot money, where non-state actors gain power, where the great turn away from science into magical thinking seems all but inevitable, where we quail from facing the civilisational threat of climate change.

We, the people, are poorly equipped to deal with complexities and hard choices.

To gain power, our politicians feed us populist solutions. We vote, we get what we voted for and we are disappointed.

By contrast, in the authoritarian democracy of our neighbour Singapore, the rulers have no faith in the ability of the public to set long-term policy parameters. And they have fared far better for removing the public from the system.

We need to consider a similarly radical fix: technocracy, Singapore-style, where we hand over much of our decision-making power to experts and step back. Only then we can avoid the fate of becoming the “poor white trash of Asia” predicted by Singapore’s founding father, Lee Kuan Yew. That insult spurred on Hawke and Keating as they reshaped protectionist Australia into a nation with global outlook.

Since then, however, we have sunk into a disaffected populism focused on short-term solutions.

To progress, we need to examine how Singapore leveraged its small bargaining chip—location and people—into a world-beating solution.

In Singapore, technocracy has been planted deeply. Public servants are expected to be technically minded, long-term thinkers and with a deep utilitarian streak. The late Lee Kuan Yew — a longsighted genius with a ruthless streak — is often credited with taking a small ex-British island expected to be a failed state and turning it into an economic powerhouse: an export-oriented manufacturer, a great port, a flight hub, a financial centre, a city-state with the third highest per capita income in the world. But Lee was just a man. Singapore’s success came from its system of expert rule, focus on meritocratic talent and long-term thinking.

How does it work in practice? Take housing. In the 1950s almost all Singaporeans lived in slum-like squatter huts. When Singapore achieved self-rule in 1959, the government set parameters — what needed to be done — and the technocrats got to work, figuring out how it could be done. The result? Eighty per cent of Singaporeans now live in government-built flats.

In a technocracy, Italian sociologist Luigi Pellizoni argues, “the elite is suitably ‘protected’ against the rest of society and is able to perform its tasks efficiently”. Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has made this explicit. Our system, he said in 2005, “shielded civil servants from political interference, (giving them) the space to work out rational, effective solutions for our problems [so they can] practise public administration in almost laboratory conditions.”

The result, observes Singapore specialist Professor Michael Barr, has been the enshrining of pragmatist utilitarianism as the highest national good. Cyberpunk pioneer William Gibson famously satirised that approach by dubbing Singapore “Disneyland with the Death Penalty”. But it’s far more than that. In Singapore’s clockwork economy, authoritarian democracy and technocratic operating system, we glimpse a future China — and through that lens, a future world order.

When technocracy is done well, it improves on Western antagonistic democracies. In the West we have deliberately introduced sand into the cogs of government: every agenda must be contested, every voice heard, every source of power opposed. We do not trust our popularly elected rulers with the power we give them. But in this age that’s a recipe for political gridlock or populism.

Singaporean-style technocracy does away with populist pressures.

It offers citizens a different deal: recede from public life in return for stable government, long-term thinking, and economic growth. You may well still be involved in public life — but in your expert capacity, contributing to a specific policy area.

How can Australia best learn from Singapore? Our system already boasts a number of technocratic elements. Our representative democracy is already one step removed from direct public rule, which California’s experiments with referenda have proven unworkable.

The Reserve Bank is a technocracy, run by experts and freed from public input. So too our legal system and our public service, our regulators and our anti-corruption bodies, and these systems, by and large, run the more smoothly for not having our input. We need to continue down this path and devolve more power to technocratic bodies of experts, while increasing the terms of government.

When Plato saw his fellow citizens bay for the blood of his great teacher, Socrates, he was appalled. Let the people rule, and they would act like a mob. His solution? A society ruled by far-sighted philosopher-kings. A technocracy. What he did not foresee was that his ideas would flower not in the West — despite a Depression-era flirtation — but in Asia. The Asian Century is built on technocracy, pioneered by Japan, perfected by Singapore and in progress in China. Technocracy is resurgent, and unruly capitalist democracy is hollowing out.

In 1947, as a devastated Britain began rebuilding, Winston Churchill stood in Parliament and recited an old line. You already know it. “Democracy”, he proclaimed, “is the worst form of government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.” That may once have been true, but it is true no longer. Singapore offers us a promising new variant to try: government for the people, without the people.

Doug Hendrie is an author and lecturer in the School of Culture and Communication at the University of Melbourne. His latest book is Amalga-Nations: How Globalisation is Good.

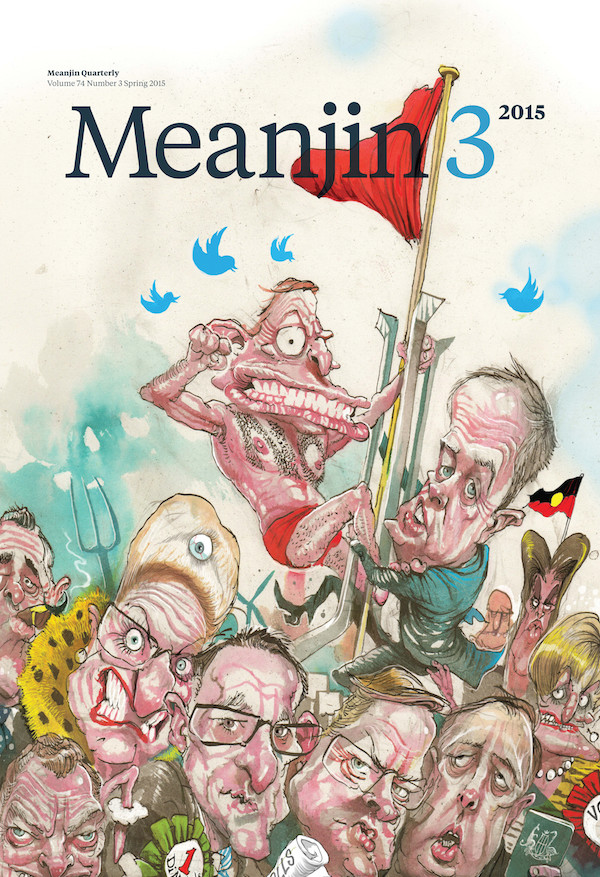

This essay was first published in Meanjin Spring 2015. Volume 74, Number 3. The issue was co-edited by University of Melbourne Vice-Chancellor Glyn Davis and University of Melbourne academic Dr Gwilym Croucher.

Paperback $29.99/eBook $9.99. https://www.mup.com.au/items/162492

Annual Subscription $100. http://meanjin.com.au/subscribe/

Banner image: The Singapore skyline at night, looking across to the Marina Bay Sands Hotel. Picture: Anh Dinh/Flickr.