Championing Indigenous women politicians

The theme for 2020’s National Reconciliation Week is ‘In this Together’; an edited extract from a new book celebrates the contribution of Australia’s Indigenous women in political leadership

Published 27 May 2020

In 1901, Australia became a federation and adopted a formal constitution that excluded Indigenous Australians from participation.

After the national referendum in 1967 granted both citizenship and the power to vote to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, it took five years for the first Aboriginal person to win a seat in federal parliament (Senator Neville Bonner), and 47 years for the first Aboriginal woman elected to federal parliament (Senator Nova Peris).

In the past two decades, more and more Indigenous women have moved from community-based politics to the parliaments.

Many Indigenous politicians have come to parliament via advocacy and working inside Indigenous organisations. It’s a pathway that honours these individual leaders’ connection to and advocacy for their Indigenous communities.

In 2020, the theme for National Reconciliation Week is ‘In this Together’ and it seems quite pertinent given the way that the world has changed so quickly over the past few months.

We have witnessed examples of positive (and not-so positive) leadership from our political representatives and seen how quickly a political and social systems can move and adjust to changing times.

In Australia, one of the standout examples of political action is that within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities themselves.

The pandemic threat has amplified the standing call to action to protect our most vulnerable and to preserve the knowledge of our old people. This has resulted in a warm embrace of cultural values, traditions, knowledge transfer and collective inspiration to rise up through our communities and our leadership.

Now is the time to celebrate Indigenous women in political leadership. Here, we champion the voices of three women – Linda Burney, Alison Anderson, and Nova Peris – and their pathways into the political arena. But as you will notice, their experience is certainly not wholly positive.

Working for social change from inside the parliament can be slow and compromising at best, for these three trailblazers the platform that being a parliamentarian created draws influence but also intensifies racism.

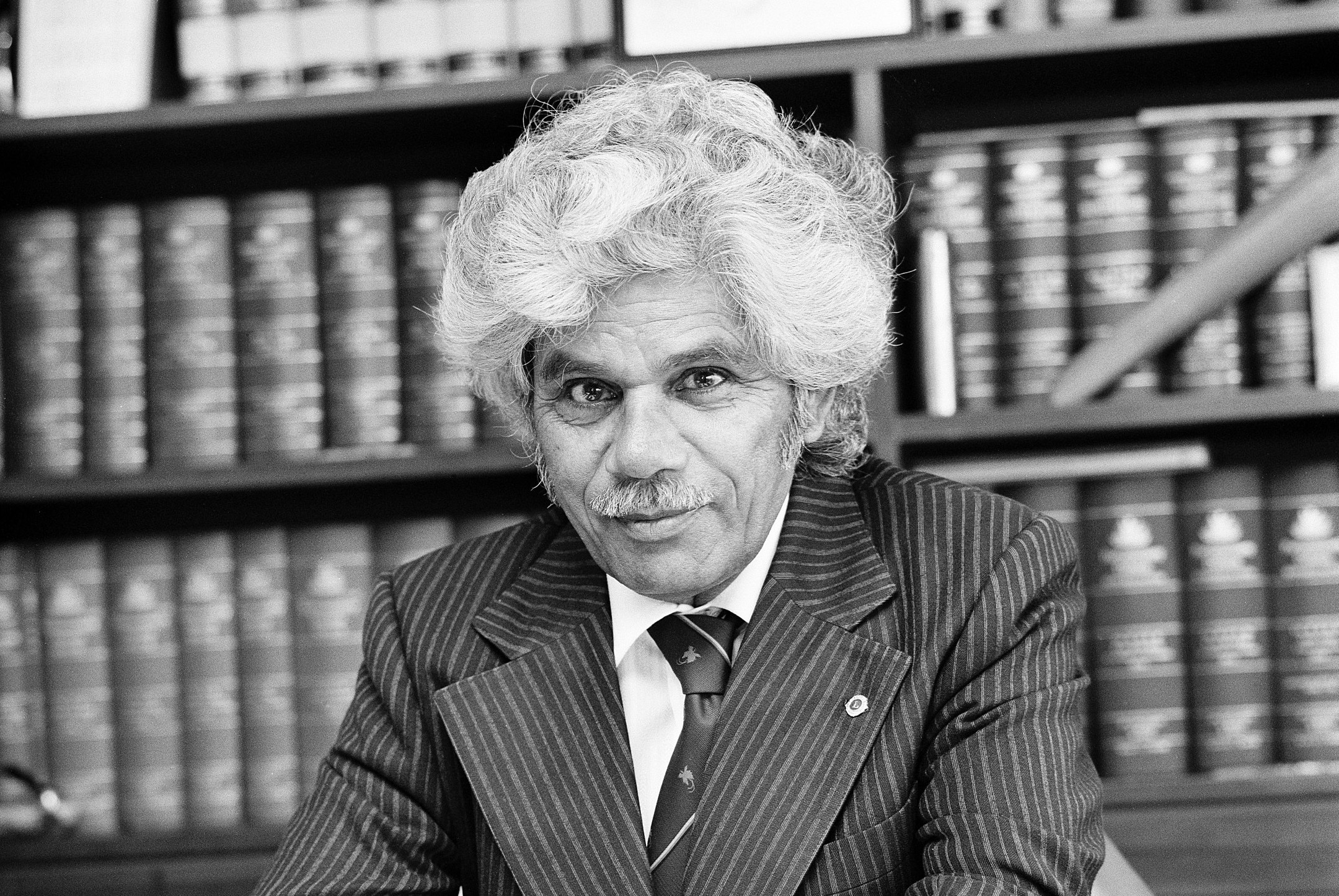

Alison anderson

Alison Anderson, born in the remote community of Haast’s Bluff in the Northern Territory, spent most of her career working in Indigenous community-controlled organisations and as a community elected representative and as Commissioner of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission.

Arts & Culture

Conserving Australia’s cultural record

During her career Anderson, who speaks six Indigenous languages, demonstrated a unique ability to directly speak to, and represent, a range of remote communities in Central Australia.

Joining the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly in July 2005 as an Australian Labor Party (ALP) representative as the Member for MacDonell, Alison claimed her seat with a 30 per cent swing against sitting member and Minister John Elfernick.

Anderson was certainly a star candidate for the ALP, but it was her community and kinship relationships that served her well. She remained a member of parliament for eleven years, switching to an independent, the Country Liberal Party and the Palmer United Party during that time.

She told us that finding out who was making decisions on behalf of Indigenous people was a big motivator for her running.

“Suspicion has led me to where I am because I really wanted to see how people make decisions on our behalf, how they implement it and these people have got no idea. It’s based on data and information completely outside of our realm. They don’t understand our lives, the way we perform, our culture, our identity.”

Ultimately Anderson was hindered in delivering a range of significant changes to remote Aboriginal communities by all of the parliamentary party machinations she was a member and representative of.

The move from community-based organisational advocacy and work into the parliamentary realm provided many impediments to achieving the kind of change Anderson was seeking to enact.

Politics & Society

Going beyond healing to build Indigenous power

Linda burney

Linda Burney, a Wiradjuri woman from New South Wales, entered state parliament for Labor in 2003, before transitioning to federal parliament in 2016.

Before her parliamentary career, Burney was diligently and passionately working for Aboriginal communities in education, both in the state government and in community-controlled organisations like the Aboriginal Education Consultative Group where she pushed for the first Aboriginal education policy in Australia.

Burney told us that her cultural identity was critical to the decision to enter politics, which she viewed as both a platform and a stereotypical container she was determined to break apart.

“Aboriginality doesn’t restrict you, and I wanted to demonstrate that I was quite capable of being a Minister and my Aboriginality was a bonus.”

These words predate her move to the federal parliament, which has seen Burney continue her incredible career representing people of her electorates (Canterbury New South Wales/Federal seat of Barton), but also for representing Ministerial appointments as diverse as education, fair trading, youth, sport and recreation, and human services.

Burney has flourished in the parliament rising to every opportunity to bring her intelligence, work ethic and world view to her work.

Business & Economics

Closing the gap in the Indigenous business sector

Nova peris

Nova Peris is a descendant of Yawuru, Kiga and Murran/Iwatja tribal nations.

An Olympic gold medallist, Young Australian of the Year, and all-round ambassador for Indigenous women, Nova Peris is a great role model for Indigenous excellence.

Peris made history in 2013 by becoming the first Australian Indigenous women elected to our federal Parliament, 47 years after Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were given the power to vote in Australia.

Peris entered federal parliament as a Labor senator in 2013 after a controversial “Captain’s pick” by Prime Minister Julia Gillard. Peris faced substantial racial vilification and spoke openly about the attacks she endured while in office. Peris described politics as a game, often played out in the media.

“It is a nasty and vindictive world, and they will do all that they can to smash you. The media certainly play and contribute to that. I didn’t like to attack people, but this is the game; you are dealing with people’s lives.

“The way I deal with this is to constantly have this hat on – my job here is to make a difference. As long as that’s my job and decisions are made, policy decisions are made, funding cuts are announced, they have a huge impact on people’s life, I will come out and say that it is a lousy decision.”

The impact of racial vilification, including death threats, endured during her term as federal senator for the Northern Territory, and caused irreconcilable damage to both Peris and her family.

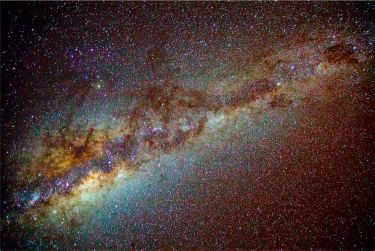

Sciences & Technology

Indigenous astronomy

In spite of this, not wholly, but significantly negative experience Peris has returned to advocating for Indigenous women and children in sport, and to taking up major national campaigns on behalf of indigenous Australia.

The heart of australian indigenous political leadership

All of these three women described how achieving a win for their constituents, however small, replenished their energy for political work.

Anderson spoke about community donations for sports events; Peris described speaking with school kids on the phone; Burney detailed how she worked with a constituent who had been homeless for two years to “win a battle over a big government agency”.

Working out how to make a difference from inside the game of politics – to be the “rod and strength” for their people (according to Anderson), to “advocate and push” (says Burney) and “to be outspoken” (says Peris) – seems to be the quest at the heart of Australian Indigenous political leadership.

These qualities and the purposeful way in which our people have been involved in governing and leading communities are also the way in which we have seen our Indigenous political leaders participate in our broader democracy.

Just as there are wins and losses in any political situation, the strength of purpose and passion resonates. This will no doubt continue to be at the heart of Indigenous political leadership in the future.

This article is based on an edited extract of Professor Michelle Evans and Michelle Deshong’s recent book chapter Australian Indigenous Women and Political Leadership in the new book Pathways into the Political Arena: The Perspectives of Global Women Leaders published by IAP.

Banner: AAP