Close to the bone: The case for remodelling racehorse training

A change to racehorse training schedules could be the key to reducing injuries on the track

Published 27 August 2015

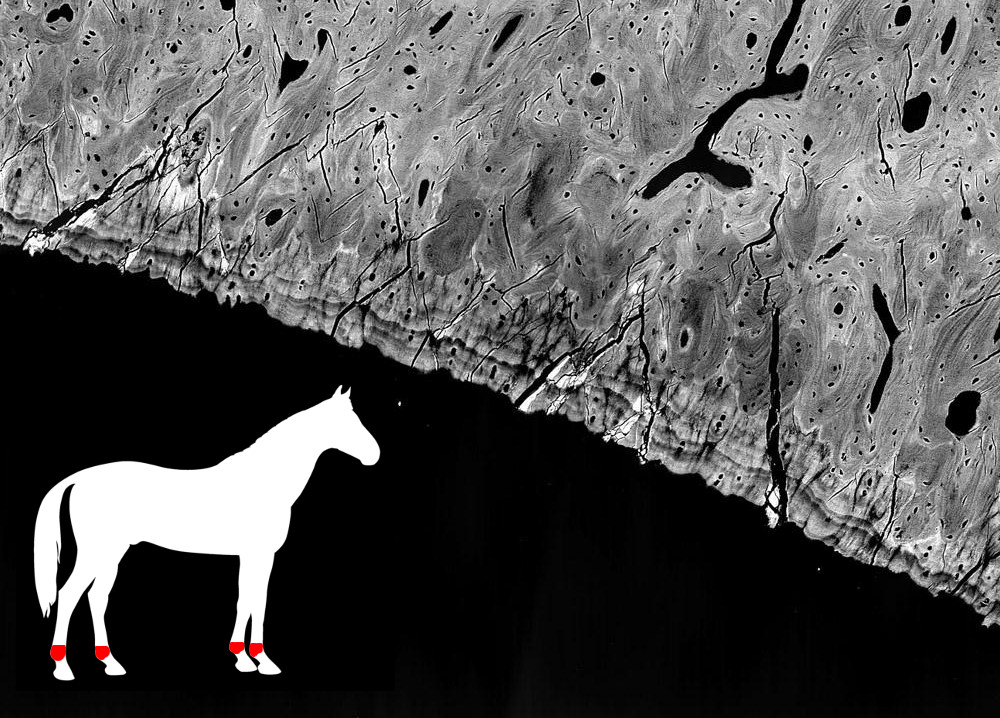

As a racehorse thunders around the track, nose flaring and limbs striving, it generates up to four tonnes of load per stride onto the lower joints of its legs. But this amazing feat of strength is not without risk.

Without proper management of a horse’s bones, over time damage to the surface of these joints leads to shorter careers, and can lead to deadly injuries on the track. In a public lecture, Chris Whitton, Head of the Equine Centre at U-Vet Werribee Animal Hospital said too often, racehorse training regimens increase this risk by not allowing horses enough time to recover between training periods.

While racing deaths are relatively rare in Victoria at less than one death per 2,000 starts, the majority of these deaths are due to limb injuries, and ninety-two per cent can be directly linked to bone fatigue. Associate Professor Whitton said:

Most of the injuries we see in racehorses are peculiar to racehorses – we don’t see them in other types of horses.

Trainers and onlookers might attribute these injuries to a bad step or fall, but when University of Melbourne researchers at the Equine Centre examined racehorse injuries post mortem, its vets found significant pre-existing microfractures in these joint surfaces.

Microfractures are tiny fractures in a bone caused when the force applied to a bone exceeds the strength of that bone.

Bone is often imagined as a hard, inflexible material but it is a living, flexible tissue - naturally resorbing damaged sections during resting periods and replacing bone material until it has returned to full strength, in a process called remodelling.

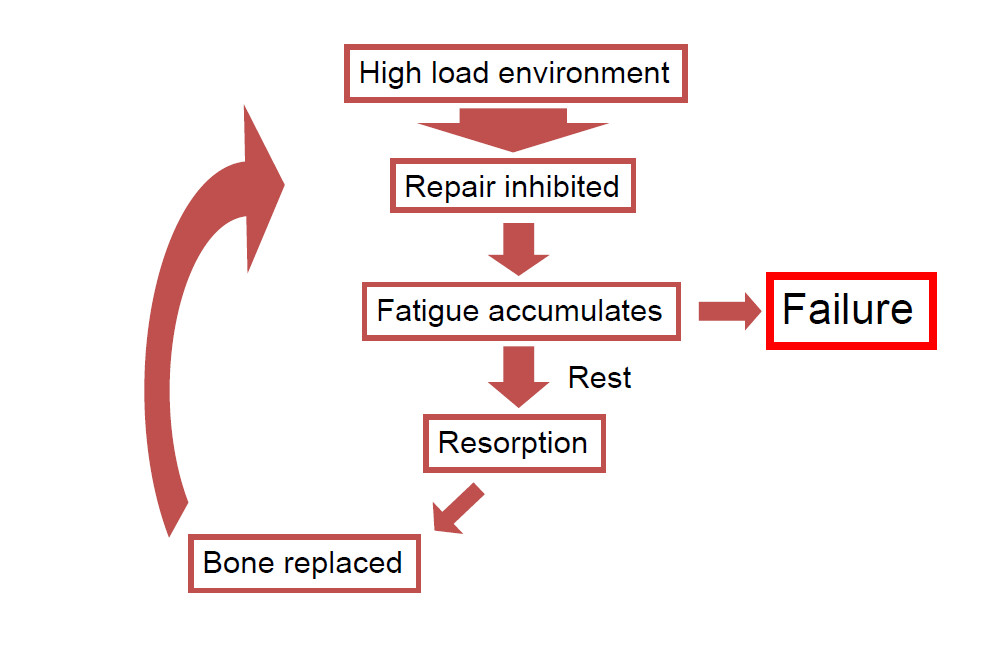

The microfractures that occur in bone are tiny and individually they are not harmful, as they occur regularly over the course of normal activity. However, repeated high loads on the joints from long training periods cause more microfractures and inhibit remodelling, resulting in poor performance and a greater risk of joint surface injuries or major fractures for the horse.

“We have a high-load environment – four tonnes with every stride. We inhibit the repair mechanism, so it is inevitable that fatigue is going to accumulate,” Associate Professor Whitton said.

“What we hope happens though, is that we stop, rest the horse, resorption kicks in, bone is replaced, we reset everything, and when we bring the horse back into work it’s repaired.”

But all too often, the cycle ends in injury instead.

“The reason is that we’re accumulating microfractures.

“Yes, we’re resting our horses regularly, but as microfractures are accumulating over the horse’s career, our rest periods are not enough.”

Associate Professor Whitton said pre-race veterinary inspection of racehorses was important, but could not be expected to pick up all horses at risk of injury. Research from Hong Kong has found that in 90 per cent of fatalities, no abnormalities were found in the pre-race inspection.

He suggested the aircraft industry’s approach to material fatigue may be a better strategy. The industry controls material fatigue with wide safety margins: if part of an aeroplane has a fatigue life of 100,000 hours, it is replaced after 50,000.

While more research is needed to determine an appropriate safety margin for assessing racehorses’ bone fatigue, Associate Professor Whitton said the prevalence of joint surface damage that the Equine Centre has found in racehorses indicates training periods are too long, and resting periods too short.

Young horses new to racing also need time for their bones to strengthen through the adaptation process, where bone volume increases.

“We need to understand that bone is a dynamic tissue and we need to work with its ability to adapt and its ability to repair,” he said.

The results are going to be fewer injuries to horses, fewer injuries to jockeys and better performance. It’s a win-win situation.

He said trainers need to have the confidence and the knowledge to know when a horse had trained enough.

“We need to maximise the adaptation to high speed and we need adequate time for bone repair... These horses will do anything we ask of them – they’re amazing animals. We owe it to them to understand them better, so that we don’t hurt them.”

Listen to the full lecture below. Lecture slides are also available.

Banner image: MJ Boswell / Flickr.