Sciences & Technology

Indigenous astronomy

The Emu in the Sky is one of Australia’s most famous dark constellations, holding special meaning for Aboriginal Australians. Now, it is being commemorated by the Royal Australian Mint

Published 28 May 2020

If you are living in the Southern hemisphere, look to the southeast after sunset and you will see one of the most famous constellations in the sky: The Southern Cross (Crux Australis).

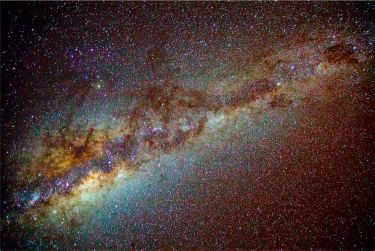

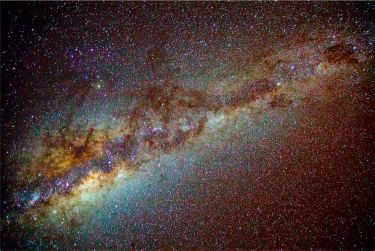

But look just below it, and you will see one of the most famous dark constellations in the sky. It is not made by connecting the dots of the bright stars into a familiar pattern. Rather, it is composed of the dark patches of the Milky Way – the space between the stars.

What you will see next to the Southern Cross is a dark patch, which astrophysicists call the Coalsack Nebulae – an area of cold gas and dust where stars are being born.

This represents the head of one of the most widely known and commonly shared Aboriginal constellations - that of the great Emu in the Sky.

The silhouette of the emu is easily seen in darker skies, with its neck going down the Milky Way through the Western constellations of Centaurus and Norma to the middle of the galaxy in Scorpius (called the “galactic bulge”).

Sciences & Technology

Indigenous astronomy

This is the body of the emu, with its legs extend down into the constellation of Sagittarius.

Ghillar Michael Anderson, a Euahlayi Senior Law Man, teaches us what the celestial emu – known as Gawarrgay in the Euahlayi tradition and Gugurmin in the Wiradjuri traditions – means throughout the year in the traditions of the Euahlayi and Kamilaroi people of northern New South Wales.

Gawarrgay’s appearance in the evening skies tells the people about the changing seasons, the animal’s behaviour, and when to hold ceremony.

As the emu rises after dusk in April and May, it is a female running. She is courting a male to mate, striding around him in a large circle, puffing out her features and making a deep drumbeat-like call.

Down here on Earth, male emus prepare the nest, in which the female lays between five and 15 eggs. She then leaves the nest in search of food. Producing such a large clutch takes a lot of energy.

Each egg weighs between 450 and 650 grams and she can lay up to three nests each single season; in case you’re struggling to work it out, this adds up to around 25 to 30 kilograms of eggs.

The emu mating season runs until early June.

Sciences & Technology

Expanding young, indigenous, scientific minds

The males sit on the nest and incubate the eggs, which lasts roughly 56 days. During this time, the males turn the eggs several times a day and do not leave the nest except to defend it.

This story plays out in the stars. During June and July, the celestial emu is high in the sky after sunset, now seen as a male Gawarrgay sitting on the nest.

The time from May to June is important to Aboriginal people who collected the bird’s highly nutritious eggs.

In the book Dark Emu, Black Seeds, Aboriginal Australian writer Bruce Pascoe discusses the emu’s relationship to native grains and agriculture, as well as how Aboriginal prepare emu eggs to eat.

It’s a relationship that prompted him to name the book after the Emu in the Sky.

In August and September, the Milky Way is perpendicular to the horizon in the southwest, looking as though the celestial emu is standing on its head.

It is during this time that the Euahlayi see the male getting up off of the nest as the eggs hatch. The males then rear the young, staying with them for several months.

It is also during this time that some Aboriginal communities in the area held initiation ceremonies.

Politics & Society

Fighting to right past wrongs

The ceremonial ground, called a Bora, is oriented to mirror the emu in the sky, aligning to the position of the Milky Way in the southwest. Bora grounds generally consisted of two circles of raised earth connected by a pathway. During these ceremonies, boys become men, symbolising their relationship to the male emus rearing the young.

By October and November, the Milky Way is low on the horizon at dusk. It is now seen as the body of the emu sitting in a waterhole. This tells the people the waterholes are full (from the rains that peak this time of year).

By December, the body of Gawarrgay has largely disappeared below the horizon. The Eualhayi say it left the waterholes when they dried up in the summer heat. Gawarrgay will not return until February, when it again peaks its head above the horizon at dusk.

The silhouette of the large flightless bird in the Milky Way and its link to the animal’s behaviour is not unique to Australia.

The Tupi people of the Amazon and the Moqoit people of northern Argentina both see this dark constellation as a rhea, a large, flightless bird very much like the emu, while the Inca of the Andes see the same motif as a cosmic llama.

This month also marks the release of 5,000 commemorative coins by the Royal Australian Mint, featuring “Gugurmin: the Emu in the Sky”, so named in Wiradjuri traditions. The artwork, showing the constellation set in the Milky Way, was produced by Scott ‘Sauce’ Towney, a Wiradjuri artist from Peak Hill in New South Wales.

Health & Medicine

Backing the strengths of Aboriginal young people

His uncirculated $A1 coin design shows a male Gugurmin sitting on a nest and a trio of young men dancing in a Bora ceremony.

If you’d like to know more about how Aboriginal people collected emu eggs, you can watch this TEDx video by Wiradjuri astrophysicist Kirsten Banks.

Associate Professor Duane Hamacher is the chief consultant for the Emu in the Sky coin produced by the Royal Australian Mint. Trevor Leaman commissioned the Gugurmin artwork from Scott ‘Sauce’ Towney through the Wiradjuri Constellation Artwork Project, with the assistance and collaboration of Palawa artist, Tina Leaman.

Banner: Getty Images