Politics & Society

International court to decide if we have a ‘right to strike’

From wages and working conditions to the eight-hour day, a new book brings together some of the life stories of the people who propelled Australia’s union movement

Published 13 May 2025

By the time Ellen Cresswell was called on to testify before the Royal Commission in August 1883, she had led a strike, been sacked, been widowed, founded a union and grieved the loss of a child.

Having spent the majority of her adult life working as a tailoress in factories across Melbourne, Cresswell was highly skilled in her trade, but she still had trouble making ends meet.

Like most tailoresses, she was not paid an hourly wage, but a set rate for each article of clothing she completed.

It was common for workers such as Cresswell to finish their day at the factory and then to take more garments home and toil through the night. Days spent at one machine were followed by nights bound to another.

If workers complained about the low rates of pay, Cresswell testified, “we are told that the market is full of labour, and unless we do as required, we can go”.

The commissioners had gathered at the Melbourne Trades Hall, the imposing headquarters of the local union movement.

The commission had been convened to investigate working conditions in Victoria’s factories, and these learned men wanted to hear directly from the colony’s workers about their experiences and the reality of their working lives.

Politics & Society

International court to decide if we have a ‘right to strike’

When Cresswell was asked by the commissioners if she had ever ‘found any difficulty in arranging with any of your employers as to what would be considered a fair rate of wages’, her answer was emphatic: “Yes; it has been our complaint daily, that for the last thirteen years there has been an endeavour to pull down prices.”

This was a matter of life or death for Cresswell.

In the 1880s, Australia’s colonies provided scant social welfare. Health and safety protections were sparse and poorly policed. There was no such thing as a minimum wage.

To survive, Cresswell had to sell her time and ability to work as a commodity on the labour market; her labour power was one of the few things she had to sell.

The wages that she received reflected the going market rate, usually determined by what the employer said they had the capacity to pay. This was often well below what Cresswell knew her labour was worth – but what option did she have but to accept the wages offered?

To complain or argue over rates was to run the risk of dismissal. The threat that her employer could always hire somebody else was constantly looming.

“I consider,” Cresswell concluded, “we are no better than white slaves with our employers.”

Alone, as an individual selling her ability to work on the labour market, Cresswell lacked power. It was the employers who controlled the work that was allocated, at what price and to whom.

Alone, she had no recourse but to accept this state of affairs and to endure as best she could. But Cresswell was not alone.

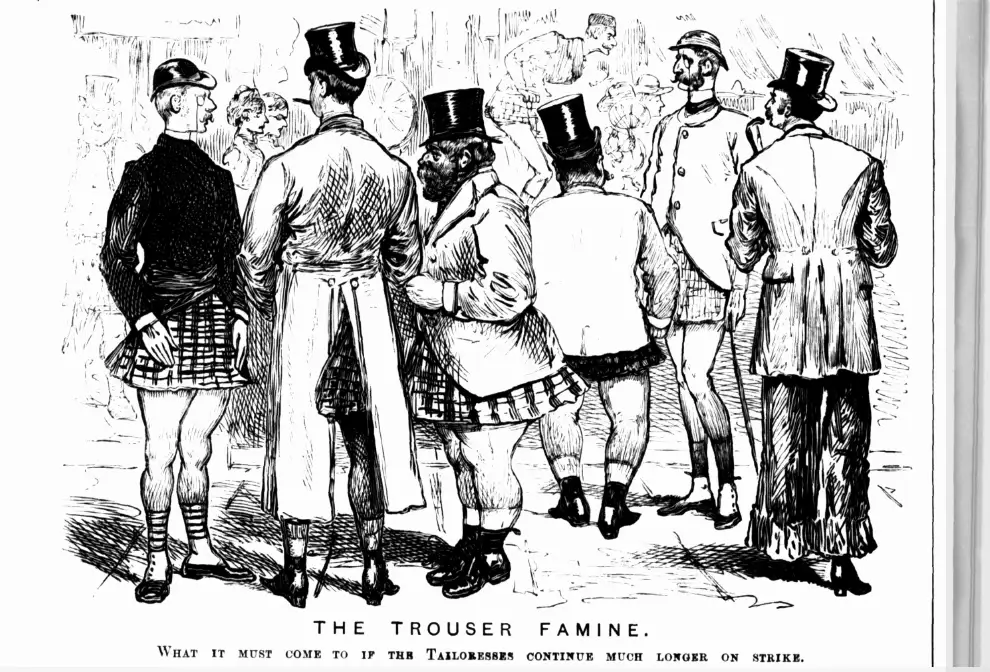

In 1882, Ellen Cresswell had been one of the leading figures in a strike of tailoresses in Melbourne, and over the course of the struggle, these women workers had not only won a pay increase but also founded their own trade union: the Victorian Tailoresses’ Union.

Cresswell’s story was a common one for workers in the late nineteenth century.

Arts & Culture

Myths of nations

They sold their time and ability to work on the labour market and received an often paltry wage in return. With few social protections and little government intervention, working people regularly found themselves being treated as beasts of burden, machines, or, as Cresswell would have it, slaves.

In response to these conditions, workers came together and forged new collective organisations to represent their interests.

Together, they took action to reclaim their humanity by winning wage increases and reductions in working hours that allowed them not just to survive, but to live.

Working people created their own organisations to assert their fundamental humanity by using collective power to elevate the value and conditions of their toil.

These were the origins of the Australian union movement.

Today’s unions are not the youthful and expanding movement for change that they were 140 years ago. In fact, unions have, until recently, been on a trajectory of decline.

It is not a coincidence that over that same period, Australia has witnessed growing wealth inequality, a reduction in real wages, a loosening of workplace protections, the growth of insecure work and the rise of the gig economy.

These shifts have been underpinned by laws that have impeded the ability of many workers to be collectively represented by their unions.

In modern Australia, there is a substantial safety net that supports and enhances working people’s quality of life, which did not exist in 1883.

While many workers struggle financially as work grows more insecure and real wages decline against the rising cost of living, there are also large sections of the workforce that receive better pay and conditions than would have been conceivable to even the most prosperous labourers in Cresswell’s day.

Through superannuation, workers have a guaranteed pathway to asset ownership. But even among this section of the contemporary workforce, strains are evident.

It is getting harder and harder to find a secure job, a meaningful career, to ensure pay increases with inflation, to afford a home or to raise a family. Working lives are still often under the dominion of managers who treat their workforces like machines or numbers rather than human beings.

Some workers are subject to the dominion of algorithms and rarely, if ever, meet or receive work directions from other people.

It is no accident, then, that traditional union claims are now being revived in new forms.

In the nineteenth century, unions argued that working people should have a right to a life outside of the workplace, and this spurred their campaigns to reduce the working day to eight hours.

Today, this same argument has led to the proposal for a four-day working week.

This is the story of how working people have come together and taken transformative action to claim power over their own lives.

Power at work. Power in broader society.

It is the story of generations of (imperfect) reformers pursuing a humanising mission, one that was transformed and expanded through the actions of excluded communities themselves.

It is the story of a movement, and it is the story of the nation that the movement helped to shape. It is a story of the past, but one that illuminates the possibilities of the future.

And it begins with a small group of working people who came together to demand a change to their working lives, with no idea that what they were about to achieve would not just alter this country’s history but reverberate throughout the world.

This is an edited extract of No Power Greater: A history of union action in Australia by Liam Byrne. It’s published by Melbourne University Press and available in store and online.