Arts & Culture

Restoring one of the world’s rarest maps

Our cultural record is the history of Australia’s identity, and, unless care is taken to conserve it with a clear cultural understanding, its context could be lost

Published 23 September 2019

At the Grimwade Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation, Western disciplines like chemistry, physics, art history and archaeology help us to analyse, understand, preserve and restore Australia’s cultural heritage.

It’s part of a history of conservation that stretches back centuries; emerging from the Western intellectual tradition of universities, museums, libraries, archives and galleries throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

But when considering a Gunditjmara stone axe, a Murrinh-patha hair-belt, a Yolngu spear, a Gija painting crafted with local ochre, a giant bronze Mirrawong boab sculpture, or a Church banner constructed in poster paints on cotton at Balgo, it’s clear that Western intellectual tradition falls short.

It simply isn’t possible to make informed decisions about the best way to treat the object if all we have to rely on is an intellectual lineage that tracks away from, and not towards, Indigenous intellectual traditions.

Lack of context brings high risk to conservation decision making as it can lead to damage to important cultural material or render valuable archival records unreadable or inaccessible.

Arts & Culture

Restoring one of the world’s rarest maps

We risk the loss of those parts of our heritage that tell us, and help us tell, the story of what it is to be Australian.

This is why, while it is important for conservators to be functionally literate across disciplines, conservation also requires functional literacy across cultures.

This has been a point of ongoing debate and discussion in conservation and museum forums for the past twenty years, but practical solutions have been difficult to achieve and cannot be driven just from one side.

It’s only possible to achieve any kind of cultural literacy if senior knowledge holders engage, on their own terms, in knowledge sharing.

And this isn’t an easy proposition.

For Australia’s Indigenous Elders in remote communities, English is often a second or third language. The tyranny of distance means that communication must be sufficiently resourced and properly managed.

Answering questions from an eager researcher may not be a priority, or it simply may not be possible.

As a way to operate, it’s not sustainable.

For close to a decade, staff and students at the Grimwade Centre and Gija Elders and artists and staff at the Warmun Art Centre, in Western Australia’s Kimberley Region, have been working together to increase knowledge across their two communities.

Each year Gija Board members, Elders and staff from the Warmun Art Centre visit Melbourne and work with Grimwade Centre staff and students, conducting teaching programs and, in turn, learning about conservation from a lab-based university perspective.

In turn, Grimwade Centre staff and students visit Warmun where they are taught by Gija Elders Centre about the importance of cultural context and understand the significance of learning Gija knowledge on the country where this knowledge is embedded.

The partnership was forged as a result of the devastating flood that destroyed the Warmun township in a few hours in March 2011.

Staff and students from the Grimwade Centre worked with Warmun Elders to determine how best to save over 450 wet and mouldy significant objects and artworks from the Warmun Community Collection.

This collection includes works by some of Australia’s most important artists including Rover Thomas, Queenie McKenzie, Hector Jandany, George Mung Mung, Jack Britten, Paddy Jaminji, Rusty Peters, Mabel Juli, Lena Nyadbi, Madigan Thomas, Nancy Nodea and others.

Arts & Culture

Rebuilding cultural heritage after disaster

One important work that was conserved after the flood was Nancy Nodea’s painting Ngalangangpum School, which tells the story of the beginning of two-way education at Warmun; first with the Gija Elders and Josephite nuns educating young Gija people in both Western and Gija knowledge under the shade of the white gum tree, then under the bough shed and finally in the school.

When this work was rescued from the flooded Art Centre, a day after the flood, mould was already starting to grow over the surface.

Triage treatment halted the mould until the work arrived at the Grimwade Centre where it took several weeks to carefully remove the mould and encrusted mud.

As paintings at Warmun are made of ochre, the removal of mud, which in reality is wet ochre, means carefully swabbing of the surface using small, cotton wool swabs and deionised water to ensure the ochre of the painting wasn’t being removed with the mud.

Today, this artwork sits in the reception of the Ngalangangpum School at Warmun, telling the story of the beginnings of the school and of the system of two-way learning, which is now shared with the University of Melbourne.

In 2014, this partnership was formalised by the ‘Bangariny-warriny jarrag booroonboo-yoo’ (two good ideas talking together) Two-Way Knowledge partnership.

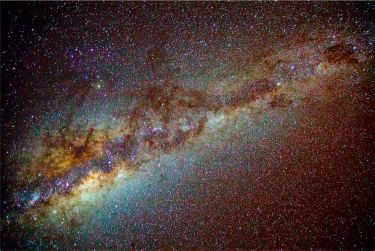

Sciences & Technology

Indigenous astronomy

The Partnering Document opens with a clear understanding about how this relationship could and should work:

“Teaching and learning has always been right at the heart of Gija ways - from Bush, to Boarding School, to Warlarri (White Tree), to the Bough Shed, and now Beyond - to the University of Melbourne.

“This new and bigger partnership will concentrate on ‘Two Way Learning’ in Arts and Education and will be about different areas of knowledge, not just conservation and art. Universities call these areas ‘disciplines’.

“The University is poor at understanding its place in Australia and wants to learn more about our Indigenous history and how this could make a difference to education and learning into the future.”

As a result of the agreement, the course subject Ngarranggarni Gija Art and Country was included in the curriculum, and was trialled at Texas Down in 2014 with artists Patrick Mung Mung, Betty Carrington and Nancy Nodea as lead teachers.

Ngarranggarni is the belief and knowledge system that guides the Gija way of life.

The Gija ancestors established Ngarranggarni when they created the land, the plants, the animals and the people. Ngarranggarni defines who Gija people are and sets out clear rules for how to behave properly as a member of Gija society, including family and clan relationships and connection to, and responsibility for clan country.

Gija Elders hold the senior knowledge about Ngarranggarni and are the custodians of that Gija knowledge. They are responsible for keeping it strong, and for teaching it to future generations.

Environment

Plants tell stories of cultural connection

This knowledge cannot be passed on without the permission of the Old People, but it is now taught to students each year as part of this subject.

While the partnership enables the sharing of particular knowledge about Gija culture in ways that are Gija-led, it also shares important lessons about life in a remote Indigenous community and life at a university.

Warmun is not alone in holding an important community collection.

In 2017, the Arnhem, Northern and Kimberley Artists Aboriginal Corporation (ANKAAA) commissioned the Grimwade Centre to examine issues relating to community collections held in remote Indigenous communities across the Top End and north Kimberley.

The report, Safe Keeping: A Report on the Care and Management of Art Centre-based Community Collections identifies a number of critical needs including the ‘urgent need to capture knowledge about collections held by Elders and senior knowledge holders before it is too late’, ‘greater recognition of the close relationship between strong community collections and production of vibrant, contemporary art’, and ‘the importance of community collections to the revitalisation of culture for youth’.

The partnership between the Warmun Art Centre and the Grimwade Centre is based on the mutual understanding that together we can do much more for our two communities than working separately.

It has shaped the way students at the Grimwade Centre are taught, and engaged in proper ways with knowledge, history, culture and lore that are instrumental in defining what it is to be Australian.

To learn more about the partnership between the Warmun Art Centre and the Grimwade Centre, please visit alumni.online.unimelb.edu.au/warmun.

Banner: University of Melbourne