Business & Economics

China’s economic evolution in the Year of the Dog

While Australia wrestles with committing to recommendations in the Gonski report on education, China is embracing student-driven learning, improving rural education and bridging the tech-divide

Published 30 May 2018

Picture a perfectly still pond of water. Mirror-like. A single drop of water hits the surface and measured ripples spread across the pond.

Recently, while I was in Hangzhou, the capital of China’s southern Zhejiang province, these ripples were evident in the education ambition and infrastructure unfolding in the country.

Hangzhou’s economy, thanks to ecommerce industries like Alibaba, is China’s fourth largest. The city, with a population of almost 9.5 million people, is investing heavily in education at multiple levels. For example, Daguan Middle School Education Group in Hangzhou, is building one of the largest Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) centres in the country.

But it’s not just these tangible changes to infrastructure, there’s social change too. School principal after school principal has a keen focus on the student, often making statements like “a good diploma does not necessarily make a good life” and “physical and mental health are more important than test scores”.

These ripples of change are spreading faster and with more commitment than I currently see in Australia. However, there are huge issues of equity and bureaucracy to navigate in China – while permission is one thing, courage to change is another.

Business & Economics

China’s economic evolution in the Year of the Dog

This is true for Australia too.

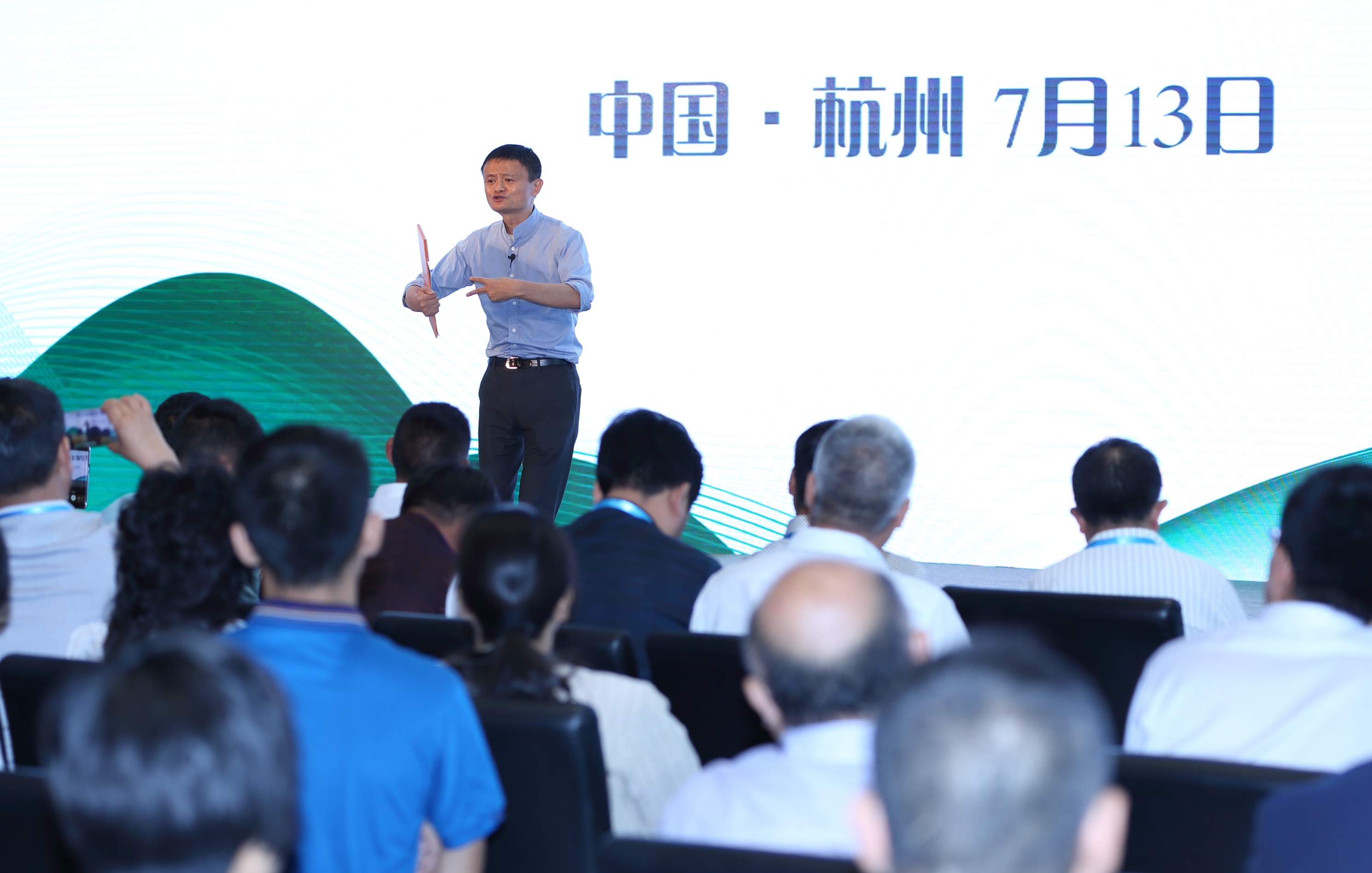

Some of these issues are powerfully brought home by an initiative funded by the Jack Ma Foundation. The charity was launched in 2014 by Jack Ma, founder and chairman of Alibaba Group. This year, the Foundation is investing significant funds, technology, and program streams in addressing how best to support rural education and educators.

One solution is providing a greater number of high-quality education graduates with incentives that encourage them to work at rural schools. In December 2017, the Foundation announced plans to invest around 45 million US dollars over the next ten years to encourage graduates to teach in rural areas.

Graduates would also receive five years of professional learning support. Before founding his e-commerce empire, Ma was an English teacher in Hangzhou and he has become a passionate and committed advocate for improvements in rural education.

Bridging the tech-divide is also key. As you head west into China, the access to reliable and current technology devices and internet becomes weaker. How schools access the kind of services and resources available in well-financed schools near the cities is a challenge Chinese education sectors are looking to confront.

While the scale of the issue is significantly different, these ambitions mirror the challenges facing Australia’s own education system.

Back to those ripples of change…

They appear again when looking at the shifts occurring in the curriculum in China. Directors at Bureau and Provincial levels have spoken of the push for capabilities as important criteria for learning .

These include capabilities like creative problem-solving skills and ‘fostering the scientific spirit’ in children as crucial priorities. This is about learning that is designed to connect children to the environment, to connect them to business technology, and learning that connects children to each other as key elements in China’s education programs today.

These are also supported by the development of impressive teacher-training centres, like the building at the Yuhang Education Bureau that is home to 14 floors of diverse education labs and a four-court physical education complex. There’s also the Cross-Border Trading Town in Hangzhou that covers a whopping 2.9 square kilometres and was built to drive new international services and entrepreneurship.

Standing on that site, I could see how an ‘innovative, invigorated, interconnected, and inclusive’ society was coming to life. This description was taken directly from the theme of the G20 Summit held in Hangzhou in 2016... and it is already being built.

The ripples that deepen learning are on our doorstep.

The connections to educational change, curriculum capabilities and better infrastructure are certainly there. And there are opportunities for Australia to develop stronger inter-cultural relations with education leaders and institutions in China.

Universities like East China Normal in Shanghai are gunning to offer ‘double-first rate’ courses. Innovative schools like Beijing Academy are scaling up beyond middle years into primary and high school mega-centres. They are using the powerful lessons of student-driven learning that they have become renowned for.

While in Australia we continue to wrestle with making commitments to Gonski and we struggle with the fragmented layers of our own education system, China is well and truly ready to transform key aspects of its own education systems.

Perhaps there’s something to be learned from the ripples China’s creating in education.

Hamish Curry was in Hangzhou speaking at the Grand Canal-Gongshu Education Forum aimed at improving understanding and promoting collaboration between China and Australia in basic Education (Year 1 to Year 9). It’s attended by government officials, education experts and school leaders from both countries.

Banner: Getty Images