Cris Jones on The Death and Life of Otto Bloom

It’s taken a while to complete his debut feature but Jones knows time is relative, and sometimes works in reverse

Published 22 July 2016

Here’s a thought experiment. Picture yourself studying at film school, with an ambition – naturally enough – to direct films. Bearing in mind how much can go wrong in the financing and production of projects, how long do you think it would take from graduation to that first film screening? Five years? Ten? For Cris Jones, who graduated from Film and Television at the Victorian College of the Arts in 2003, it’s taken a little longer.

Still, he can take solace from the fact his debut feature, The Death and Life of Otto Bloom, will open the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF) on July 28. He started writing it in 2014, and only finished it in recent weeks, which might explain his still-slightly-halting elevator pitch.

“I’ll give you a really brief one-liner,” he says, eyeing the ceiling, thinking it through. “It’s the chronicle of the life and great loves of Otto Bloom, an extraordinary man who experiences time in reverse, passing backwards through the years while remembering the future.”

Bloom, played by Australian actor Xavier Samuel, is a Bowie-esque creature who has fallen to Earth at some point in the 1980s with soon-to-be-infamous abilities, charming and perturbing everyone he comes into contact with, including the neuropsychologist called in to examine him, played in the present-day by Rachel Ward. She is one of several talking heads who recount Bloom’s story while action unfolds against a backdrop that’s recognisably, and not so recognisably, Melbourne.”

“A lot of the film was shot at Melbourne Uni,” says Jones, “even scenes that supposedly take place in New York City. Our scout just found the most wonderful locations which, shot from the right angle, helped us get away with it.”

Otto Bloom was born of another feature-film project, Byzantium, which Jones started working on seven years ago. When it hit the buffers in 2014 he found himself caught between throwing in the towel or cracking on with another project, a situation he describes, euphemistically, as “challenging”.

“Yeah, well, it was a choice of falling to pieces or taking that energy and using it as momentum for the next project,” he says. “It was difficult, sure, and I had to have a good long think about what I was doing with my life, but in a way I’m actually grateful it ended up the way it did. I think this is a much stronger project from having gone through that experience.”

In terms of story there are no similarities between Byzantium and Otto Bloom, but thematically both films examine time and memory, life and death, love and loss.

“All the big stuff, really,” says Jones. “Time is the ocean we swim in and yet we think about it such limited terms: ‘I’m running late for work’, or, ‘It’s time to go to bed’. This film is offers a post-Einstein view, where our perception of time is an illusion, and every single moment is equally and simultaneously real.

“There’s a lot of consolation to be found in that philosophy, particularly when it comes to things such as losing someone you love – the thought that somewhere in time all those happy memories you have with that person will forever be unfolding is very hopeful, very positive.”

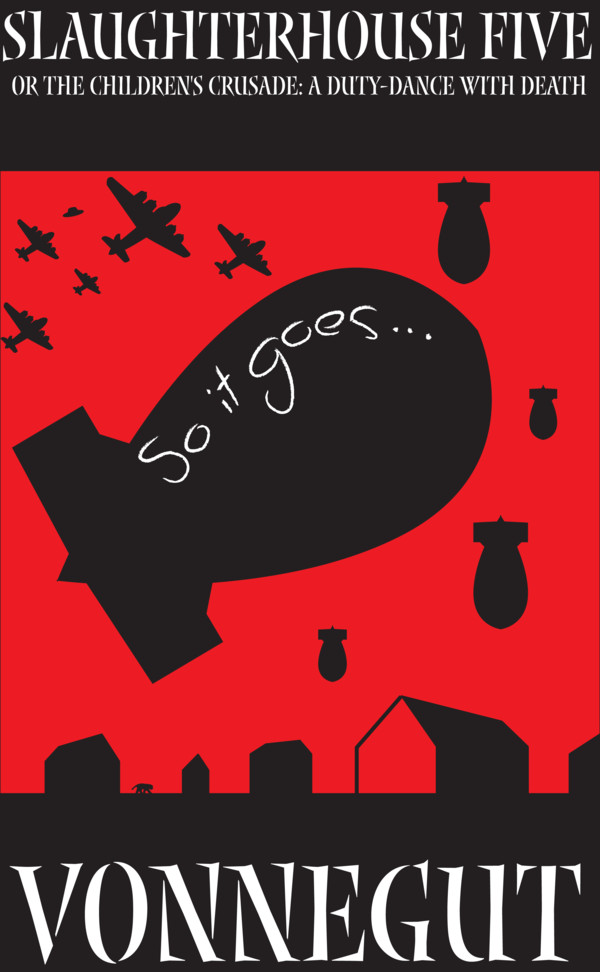

When I tell Jones the film’s treatment of those themes brings to mind the writing of Kurt Vonnegut Jr, he stands slightly from his chair, and I have the horrible impression I’ve offended him and he’s about to leave; instead he opens his jacket to show me his T-shirt. It features the Tralfamadorians, the fictional alien race in Vonnegut’s masterpiece Slaughterhouse Five who exist in all times simultaneously, past, present, and future.

“Slaughterhouse Five was a hugely formative book for me,” he says. “There’s beautiful chapter in the middle of it where [the protagonist] Billy Pilgrim is watching a documentary about the war on TV that’s just describing everything in reverse: the bombs being sucked up into planes, taken back to America, and then deconstructed into their constituent elements and buried into the ground so they’ll never be used again.

“The Tralfamadorians describe looking at a human being as like looking a caterpillar with an infant on one end and an old man on the other, and looking at the night sky as strings of luminous spaghetti. It’s beautiful stuff, and was definitely hugely influential on this project.”

Making ends meet in the years from lean to big-screen has taken various forms for Jones. A few rounds of development funding from Screen Australia helped with Byzantium, another round helped with Otto Bloom, as did MIFF, through its MIFF Premiere Fund. As well as directing short films (the award-winning Excursion, 2003; The Funk, 2008), Jones has occupied himself with editing and intermittent teaching work for Film and Television at the VCA. Bits and pieces, in other words.

“You just try to live as frugally as possible,” he says. “You don’t get to enjoy certain luxuries that come with having a full-time job. But it’s a trade-off. You’re investing your miserable existence in the hope that it might pay off and you might end up with something you can show people.”

What has he learned about himself as a director?

“Maybe that the shoot isn’t nearly as terrifying as I thought it would be,” he says. “I tend to catastrophise things and imagine that everything is going to go as badly as it could possible go. The last thing I’d directed was my short film The Funk, in 2008, and it’s easy to feel like you’ll forget what you’re doing.

“But I was surrounded by such talented and experienced people that it all went off pretty much without a hitch. I don’t want to leave it too long before the next project because you can lose your nerve in between.”

And your momentum, I offer. Jones must feel that now, at least, a sense of momentum?

“Hm,” he says, scratching his chin. “I feel a sense of exhaustion. But I do want people who see the film to enjoy it.That’s all I can really hope for.”

Banner image: Still from The Death and Life of Otto Bloom

The Death and Life of Otto Bloom receives its world premiere at the MIFF 2016 Opening Night Gala on July 28. Details here.