Politics & Society

Debate trilogy: From the mad to the bad to the crazy

There was some policy debate, but it was swamped by messages appealing to voters’ fears, hopes and insecurities

Published 20 October 2016

The third debate of the 2016 US Presidential campaign, between Democrat Hillary Clinton and Republican Donald Trump, was held at the University of Nevada, in Las Vegas.

Here, University of Melbourne experts give their view.

Trump once again preached in circular gusts of trigger words. Like a verbal cyclone, he tapped directly into the fears and insecurities of American voters.

For all the trumpeting about his lack of substance, the orange orator has thrived during these debates. He thrives because of his readiness to substitute principles of logic with principles of psychological motivation.

Trump’s backroom cell understands motivation. They know that a campaign cannot be built on a cornerstone of economic rationality if voters feel oppressed by economics. They know that choice is more powerfully inspired by appeals to fears, hopes and desires than by clarity of thought.

Clarity of thought doesn’t matter much when it comes to the final nudge towards a choice. Consider TV advertisements. How many of these rely on rational appeals?

Trump remains in this race because he speaks the motivational language of advertising. This is a language of pictures and emotionally loaded words that activate the fears and desires that preoccupy so many voters’ minds.

In this mysterious language, Trump is an icon of the 1980s. And although he is a figurehead of a ship that sailed 30 years ago, he nevertheless caters to voters’ nostalgic longing for Reagan’s boom-times.

Moreover, like Reagan before him, Trump’s TV bit-parts in American pop culture place him as a problem-solving protagonist, a man with an American agenda.

Clinton spoke an entirely different language today. Grounded as she is in the mess of managing America, she spoke more knowingly about the realities of borders, escalating conflict, a struggling economy, justice and the constitution.

"We have some bad hombres here." https://t.co/hy6qNxXL2z pic.twitter.com/9ILVlmAiwE

— NBC Los Angeles (@NBCLA) October 20, 2016

This is her weakness on this most peculiar stage.

For it is the emotions triggered by images of ‘bad hombres’, ‘Trojan horses’, making countries ‘pay up’, and ‘ripping the baby out of the womb’ that will linger between now and polling day.

What is at stake has been unpacked in the media scrum, no doubt. Nevertheless, the media’s silence over the motivational language by which today’s debate was fought should shock us.

The psychological techniques of marketing are defining our future.

Yet in the playground of political broadcasting, no one is concerned to unpack these emotional conjuring acts. Instead, the world’s media will gather around Hillary and Donald to chant, ‘fight, fight, fight’.

Emma Shortis, tutor in US history and PhD candidate, School of Historical and Philosophical Studies.

There was no handshake. And, to the disappointment of many fans of video spoofs released after the first and second debates, no shimmy. From the outset, though, there was a great deal of what almost no one was expecting: actual policy discussion.

On a number of issues, from the appointment of Supreme Court Justices, to the Second Amendment, to reproductive rights, the two candidates outlined their policy positions in detail.

Trump, to the surprise of many, initially kept his cool and wedged Clinton well on a number of issues, especially her historic support of free trade agreements.

It was when Clinton pointed out that Trump was guilty of sending American jobs overseas and short-changing American workers that her tried and true strategy once again paid off.

.@HillaryClinton trusts women & understands women's experiences. We're with her. She's with us. 🙋🇺🇸 #DebateNight pic.twitter.com/BW6LyG9ipy

— NARAL (@NARAL) October 20, 2016

Trump was unable to resist taking the bait. When he gave Clinton an opening to discuss her ‘30 years of experience’, she really hit her stride with a prepared response, the best being that she, as Secretary of State, was sitting in the Situation Room at the White House when Osama bin Laden was captured and killed. Trump, meanwhile, was hosting The Apprentice.

Clinton’s nod to reality TV brought about the long-expected degeneration into interruptions, interjections and personal attacks.

Confronted by the allegations of sexual harassment levelled against him, Trump insisted they were all ‘fiction and lies’, going so far as to accuse the Clinton campaign of orchestrating the claims and even of being responsible for violence at his rallies.

While he may have further cemented the support of his base with responses such as these, just like in previous debates, Trump surely failed in the essential task of winning over the undecided voters he needs to win. And he did much to convince those voters that the accusations levelled against him are accurate when he leant into the microphone to sneer at Clinton that she was ‘such a nasty woman’.

Clinton: "What we want to do is to replenish the Social Security trust fund..."

— CNN (@CNN) October 20, 2016

Trump: "Such a nasty woman" #Debate https://t.co/HMsvusL4Y6

The most extraordinary moment of the night, though, came late in proceedings. Asked explicitly if he would accept the results of the election, Trump responded, twice, with “I’ll tell you at the time”.

The election, according to Trump, is ‘rigged’, voters’ minds have been ‘poisoned’ against him by the media and Clinton should never have been allowed to run in the first place because she is a ‘criminal’.

Rhetoric such as this, coming from a candidate for President of the most powerful nation in the world, is both historically unprecedented, and as Clinton put it, utterly horrifying.

Despite the protestations of his supporters, Trump all but confirmed, in front of hundreds of millions of people, that he will only accept the election result if he wins.

The prospect of that happening, according to all reliable polling, is increasingly unlikely. Should Trump stand by his words, the United States is indeed, to borrow Clinton’s phrase, facing a ‘dark and dangerous’ future.

“Who would you choose as the captain of your boat?”

This is the question asked of 5 and 13-year olds when presented with the photographs of pairs of candidates for public office. The person the children chose on average won the election 71 per cent of the time

Politics & Society

Debate trilogy: From the mad to the bad to the crazy

Most of us understand leadership to be more than how you look in a photograph. We see leaders as having the ability to inspire followers with a grand vision and purpose.

We see leaders as the having the experience and expertise required to solve intractable problems. We see leaders as having the integrity necessary to make the hard decisions, and the willingness to sacrifice their personal gain for the good of the whole.

Yet how is it possible for a man to display none of these traits and yet be the chosen leader of nearly 40 per cent of the likely voters in the US?

The answer is that when choosing leaders, many people resort to intuitions and stereotypes, rather than facts and figures. Indeed, our intuitions filter out any facts and figures that inconveniently contradict our prior beliefs – commonly known as the confirmation bias.

When Trump says the Clinton Foundation is a criminal enterprise and provides a litany of reasons why – you need only ask what someone believes ahead of time to know if those reasons will be believed or even remembered.

When Trump says that ‘nobody has more respect for women than he does’ – you would be unlikely to hear people at a Trump rally laughing in disbelief.

To many, Trump looks like a leader. He is tall. He assumes dominant postures and speaks authoritatively on topics regardless of his level of knowledge. He has a lot of money and nice things. He has many of the traditional conspicuous characteristics that we associate with leadership, and has paired this symbiotically with a fear-based campaign.

His constant references to frightening imagery – a foetus pulled from her mother one day before it is born; a vast conspiracy to rig the election; ISIS taking over the US – are pitch perfect for an audience who already sees him as a strong leader who can protect them from these dark forces.

Indeed, Professor Jonathan Haidt, of the NYU Business School, has shown that those who have a stronger fear response are more likely to be conservative.

Consistently, those who are most conservative in the US support Trump by a wide margin – apparently willing to forgive a lack integrity, honesty, knowledge, experience, humility, values, and faith as long as the captain of their boat looks like the kind of captain who can protect them from the terrors of the deep.

This article has been co-published with Election Watch USA, an initiative of the Melbourne School of Government, University of Melbourne.

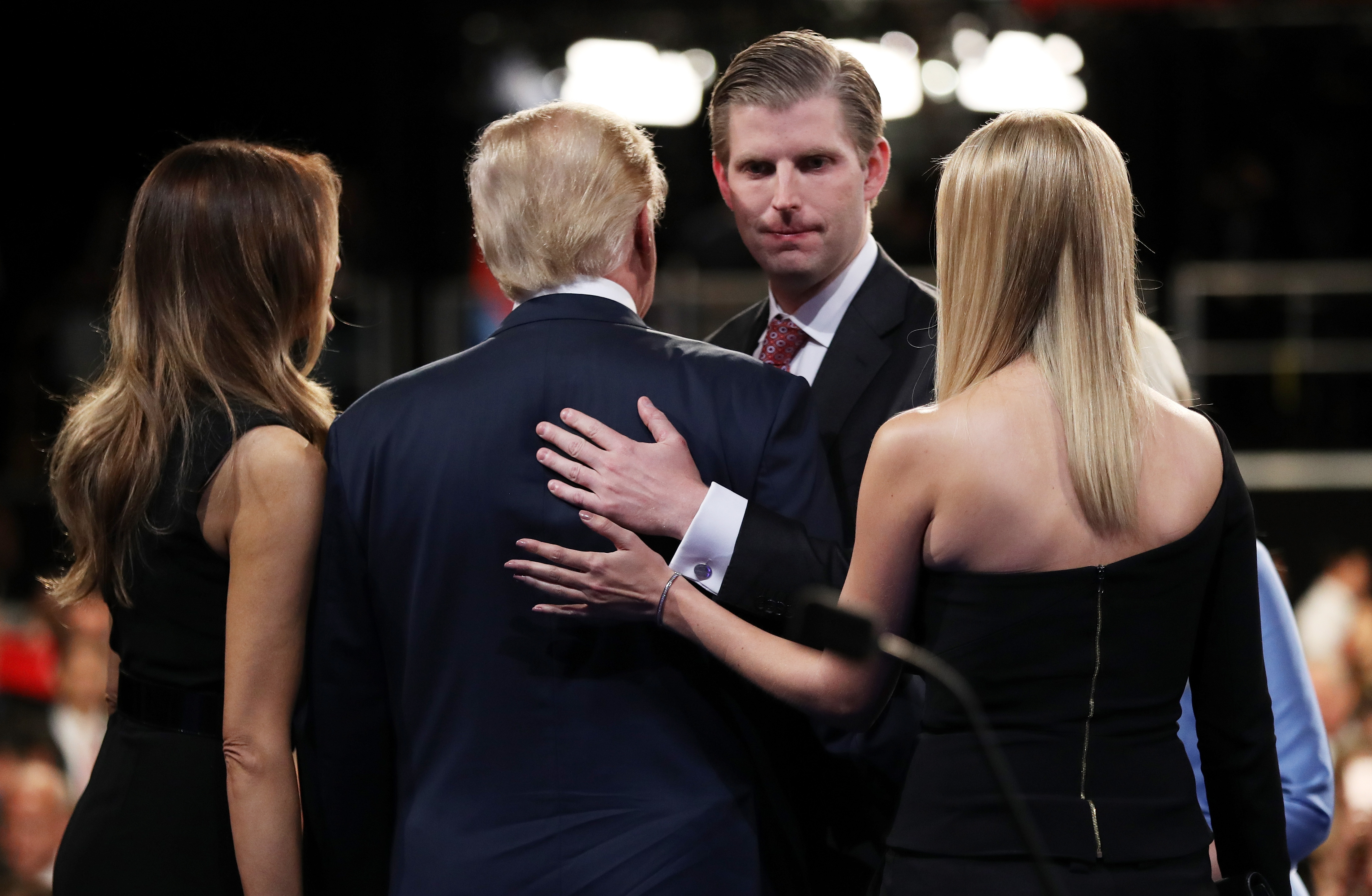

Banner: Donald Trump makes a point during the debate in Las Vegas. Picture: Ethan Miller/Getty Images