Politics & Society

Why investigative journalism matters more than ever

The recent police raids on Australian journalists are a cause of concern for many, but they also highlight the far-reaching impact of public interest journalism

Published 11 June 2019

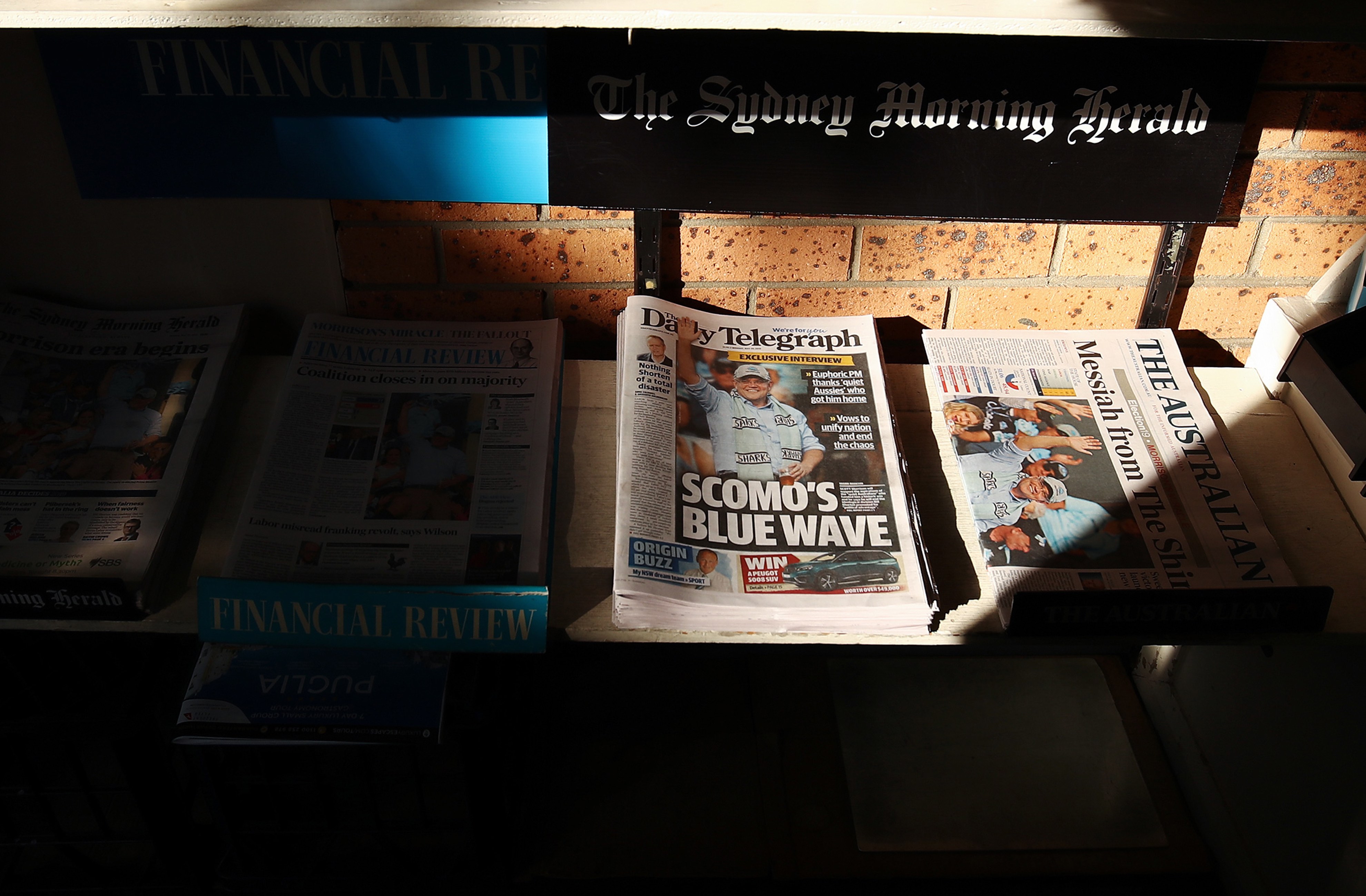

Early in June 2019, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) raided the apartment of News Corp editor Annika Smethurst. According to authorities, the raid aimed to uncover information related to a 2018 article revealing that the Australian Signals Directorate sought to spy on Australian citizens without their knowledge.

The following day, the AFP went onto raid the ABC’s Sydney headquarters seeking information related to a series of stories aired in 2017 focusing on the gross misconduct by Australian military personnel in Afghanistan.

These raids, which the AFP have somewhat unconvincingly insisted are “unrelated”, generated understandable and very public outrage.

The threats posed to journalistic freedom in Australia were discussed at length in op-eds and social media missives. The prominent UK-based human rights barrister Geoffrey Robertson described Australia as a “second-rate country” that has failed to protect its journalists.

But the raids are also important because of the attention that they inadvertently bring to the significance of public interest journalism. To understand its importance, though, we first need to understand ‘public interest journalism’ and why it’s integral to a healthy democracy.

Politics & Society

Why investigative journalism matters more than ever

To answer that first question, the term public interest journalism must be broken down into its constitutive parts. Well-known journalism and media researcher Brian McNair defines journalism as “a supplier of the information for individuals and groups to monitor their social environments.”

Traditionally, journalism has been understood as a harbinger of democracy through its role as the so-called fourth estate; its role to ensure that government, businesses and the nobility are acting in the best interest of the public.

The fourth estate model might seem anachronistic in an era where the links between the media and big business, as well as the naked political bias of certain outlets, have been amply documented.

Nonetheless, the democratising potential at the heart of this model is still applicable to journalism that reports on issues that are of public interest.

And so, public interest journalism is journalism that informs the public about matters that they need to know about, because we are affected by them. Public interest journalism helps make these matters the topic of public discussion and debate – debate that is crucial for a democracy to function.

Clearly, the two stories that led to the AFP raids were examples of public interest journalism.

How could they not be?

Politics & Society

Whose fake news?

How is the government surveillance of Australian citizens (and the implicit threat to privacy and liberty that comes with this) not a matter of public interest? Surely Australians have the right to know about the alleged misdeeds (which allegedly include the death of a child) of this country’s armed forces?

There are other local examples, too, of public interest journalism.

Think of the ABC’s expose on the barbaric treatment of Aboriginal young people in Darwin’s Don Dale Youth Detention Centre. Think of the Iranian-Kurdish journalist Behrouz Boochani’s reportage on the inhumane living conditions on the Manus Island Detention Centre that included media articles, a Twitter account, and the book No Friend but the Mountains.

Public interest journalism is also evident in the reporting of matters where it may not be immediately obvious of its significance to the public.

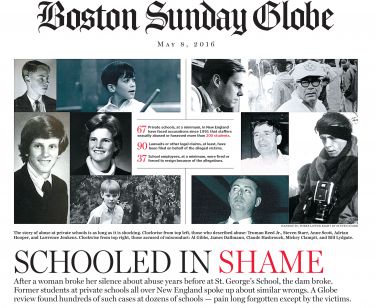

The disclosure of Barnaby Joyce’s extramarital affair is one example. In early 2019, the Daily Telegraph broke the news that Joyce (at that time the National Party of Australia’s leader) was in a relationship with former staffer Vikki Campion, and she was expecting their child.

Much reporting of the Joyce affair was sensationalistic; the Daily Telegraph cover was demeaning to Ms Campion.

Nonetheless, the affair was certainly a public interest matter.

Arts & Culture

How TV policy tuned out

Joyce has long championed the heterosexual nuclear family, and had spoken publicly about the damage that legalising same-sex marriage would supposedly do to this traditional unit.

The public has a right to know that this elected representative (whose words had doubtless caused hurt for queer couples and their supporters) was unable to practice what he preached.

We had a right to ask what Joyce’s inability to ‘walk the walk’ said about his trustworthiness as a politician. This made it public interest journalism.

Returning to the AFP raids: yes, they represent a threat to journalists and their ability to undertake their jobs. Yes, these raids will intimidate and potentially silence whistleblowers.

David McBride, the army lawyer who leaked information to the ABC for the Afghan Files and who is now facing court, has been quoted as saying: “It’s very scary. You could be talking about corruption and bribery in some industry and they could say ‘that’s national security’.”

The AFP raids also represent a threat to the very existence of public interest journalism in Australia.

There’s every likelihood that journalists could be less likely or even unwilling to report on certain matters if they stand to be accused of jeopardising national security, however improbable that threat might seem.

Politics & Society

Race, sport and media: Questioning the status quo

As one commentator noted, if reporting on army brutality or government surveillance threatened the livelihood of Australians, this would surely be known by now. Both stories are over a year old.

A large part of the problem is the lack of legal protections accorded to journalists and their sources.

Media ethics specialist, Dr Denis Muller (himself a veteran journalist and a scholar at the University of Melbourne) points out that “the laws that do exist in Australia to protect journalists’ sources offer no protection from police raids and electronic surveillance.”

He goes onto say that “Australia is alone among the “Five Eyes” countries that make up the West’s main intelligence network in having no constitutional protection for freedom of the press.”

In the wake of the raids the Centre Alliance party, a centrist Australian political party, has recommended a “constitutional amendment” that will enable press freedom to be protected.

Just what this protection will look like, and how effective it will be, remains to be seen.

But this recommendation at least acknowledges the profound harm that intimidating and attempting to silence journalists can do at the expense of what’s in the public interest.

Banner: AAP