Dinner in No-Man’s Land

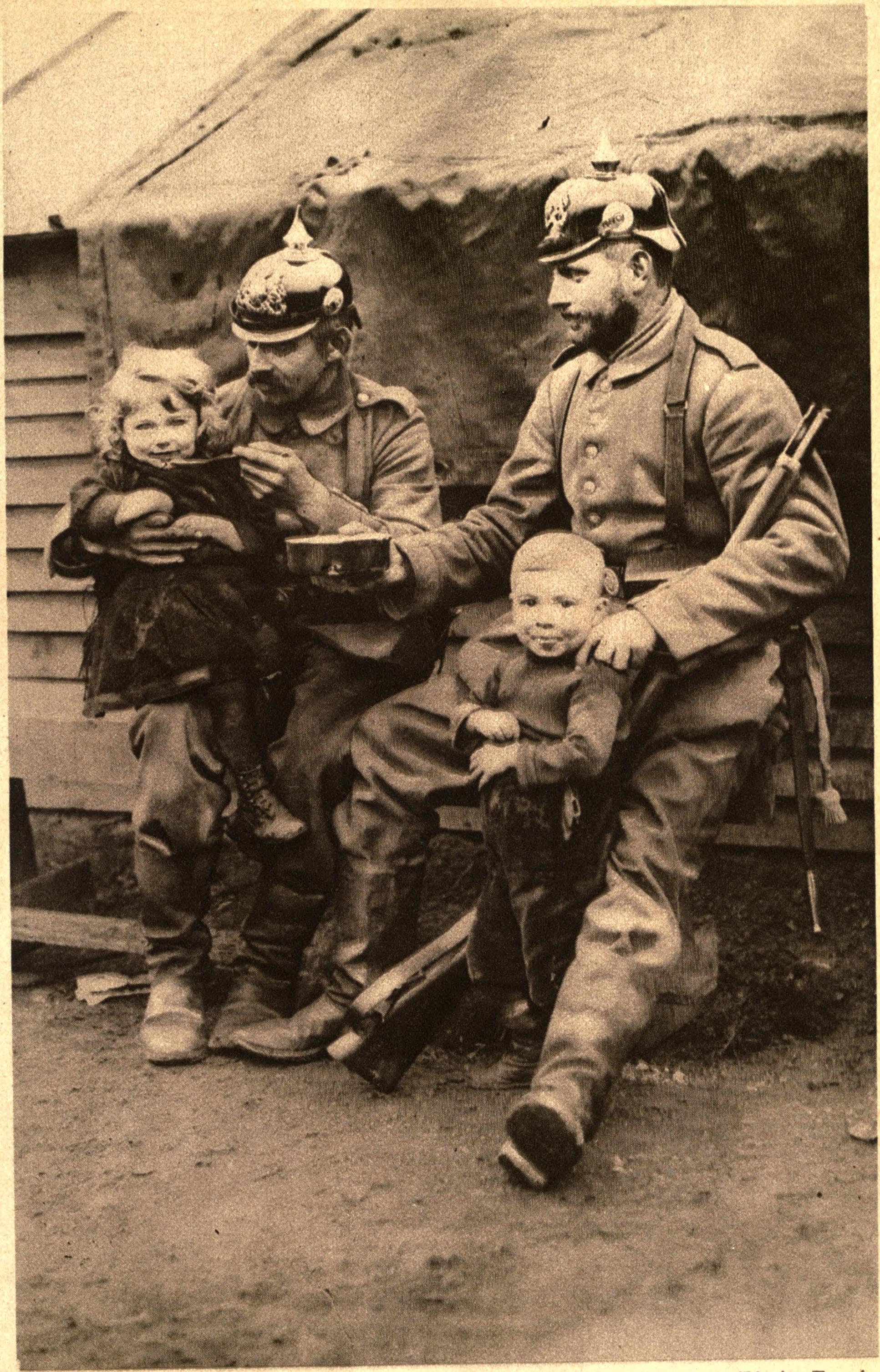

As the country marks Anzac Day, we look at how the act of sharing food during a time of war, even across enemy lines, is a potent symbol of our humanity.

Published 24 April 2017

At one point during the endless fighting in France in World War One, a tired German soldier, Wilhelm Spengler, threw himself down to rest in front of a squalid hut in a French village.

“Suddenly an old grandmother was standing next to me with a wooden dish full of milk and a slice of buttered bread. Without a word she passed both to me. I ate greedily as the old woman watched me pityingly and repeated: “Oh, the war! Oh, the war!“ I thanked the woman with a “God bless“ that I had never before meant so sincerely and deeply and, newly strengthened, I went on my way.”

Words cannot adequately capture the horror of the war for this woman, who may well have had sons or grandsons away at the front. Her offer of sustenance to the young soldier, a member of the enemy, was an act of simple humanity in barbaric times. But it was food that was the crucial medium that made this expression of humanity possible.

When we publicly commemorate past wars and conflicts, such as on Anzac day and Remembrance Day, the focus is on remembering the sacrifices made by soldiers and civilians. But we are beginning to pay more attention to the personal and everyday experiences of people during wars. Historians are increasingly delving into personal accounts to pursue what is sometimes called “history from below.” It is this emphasis on the personal that is creating the opportunity to go beyond sacrifice and to commemorate our enduring humanity in the face of war. And there are few more potent symbols of our humanity than the act of sharing food.

Food features prominently in many of the personal accounts of war that have come down to us and cultural historians are paying more attention to food as a revealing lens through which to view the experience of war. During times of conflict there is material pressure on food supplies, but also symbolic pressure on the meanings of food. Food can become an aspect of the enemy that is demonised, producing wartime epithets such as rosbif for the British, krauts for the Germans, “pork and cheese” for the Portuguese. But food can also be a strong reminder of common humanity, even across enemy lines.

Interactions such as Spengler’s that occur outside of formal structures of billets and commercial hospitality are some of the most moving illustrations of shared humanity in wartime. When people are moved to give food to a hungry person, doubtless disregarding their own hunger, the international politics of the conflict recede and we see people acting according to personal values including empathy and care.

Food and the craving for normality

In her study of British soldiers during WWI, The Stomach for Fighting, Rachel Duffett points out that the trenches were a “motherless, masculine world” that eroded gender roles. When soldiers encountered civilians – usually women and children – and shared food with them, they felt transported back to the normality of civilian life with its familiar family structures.

For example A German-Jewish soldier, M. v. d. W., describes his experiences in a largely Jewish Polish village on Rosh Hashanah (Jewish New Year) in 1914:

“I was thirsty and asked at a house for a glass of water. A Jewish widow gave me what I asked; we conversed and when she learned that I was also Jewish, she led me into a room where the Jewish festive table was set with the two candles, apples and bread. ‘You must eat here with us’, and it was useless to protest. I recited Kiddush, shared the delicious meal with the good woman and her two children, and if the conversation (half Yiddish, half German) was somewhat difficult, my deep emotion soon gave way to comfort.”

This experience afforded this soldier a precious experience of home life away from home. While culture and the fault lines of war make people into enemies, culinary traditions can bring people together in familiar ways. The Jewish villagers seemed not to care that the soldier was fighting for an invading nation.

Pity for starving French children motivated some allied soldiers on the Western Front in Douai in northern France to give up their own rations. A Canadian soldier wrote in his diary that he was out scrounging for food when he came across an army kitchen.

“It belonged to some Imperial outfit, and the cooks were generous, but I didn’t get anything there. I never asked. Seated around the cooks, on old boxes, boards, bricks, anything, were at least fifteen children, and every one had a bowl of mulligan (stew). In the background were a dozen soldiers, men who had given their dinners that those kiddies might be fed.”

Food as hope and a weapon

While civilians could be moved share their food with enemy soldiers, they were also prepared to brave enemy soldiers to give food to those fighting on their own side. Australian prisoner of war Claude Corderoy Benson recalled with anxiety the risks some French civilians took to feed a line of POWs as they were marched through their village.

“The French people got very excited and in spite of the guards, they determined to give us bread by handing it to the men between the guards. Whenever the guards saw a French person appear in the door-way of a house they would rush at them, knocking them down with the butt end of their rifle, and I saw one of the guards use his bayonet on a poor French woman who gave one of our party a biscuit, she struggled to her feet, put her hands to her face and went limping and crying into her house. I felt I would rather have died from starvation than see these women so ill treated, and wished the poor creatures would not try and help us.”

The incident is a reminder that food and its corollary, hunger, is also a weapon of war. In her heart breaking study of the 1941-42 siege of Leningrad, Darra Goldstein shows how under extreme conditions food becomes detached from its cultural meaning and hunger turns people into animals, who eat (if they can) only to survive.

Similarly, Spengler, the same German soldier offered food by the old French woman, recalled having a very different experience with food in the midst of combat and hunger.

“Over a creek we go and under cover behind a long hedge. Next to me a Frenchman, shot through the temples his head hideously swollen. I take the bread and tinned meat from his kit bag. A stab with the bayonet and the tin is opened. Hurriedly we eat the good beef. With faces on the ground we lie there and listen to the bullets whistle around us.”

A culinary transaction more diametrically opposed to that earlier caring interaction is hard to imagine. In her book Food In Conflict Zones, Katarzyna Cwiertka writes “war creates extraordinary circumstances of multicultural encounter for soldiers and civilians […]. The potential meaning of food at the front sharpens—it can become a weapon, an embodiment of the enemy, but also a token of hope, a soothing relief.”

When we look at such encounters in wartime we become alert to the potential of food to transcend enmity and restore feelings of common humanity. And we can also see in a new light the inhumanity of the conflict on all sides.

Banner Image: “Morning after Beersheba 1.11.17 Turkish Dr that we found - having a bit to eat - hotcake.” (Album caption). An image from a photograph album recording the service of Major (later Lieutenant Colonel, DSO) Thomas Joseph Daly, 9th Australian Light Horse, in Egypt and Palestine. Australian War Memorial