Politics & Society

Keeping up with the droneses: How criminal laws deal with new technology

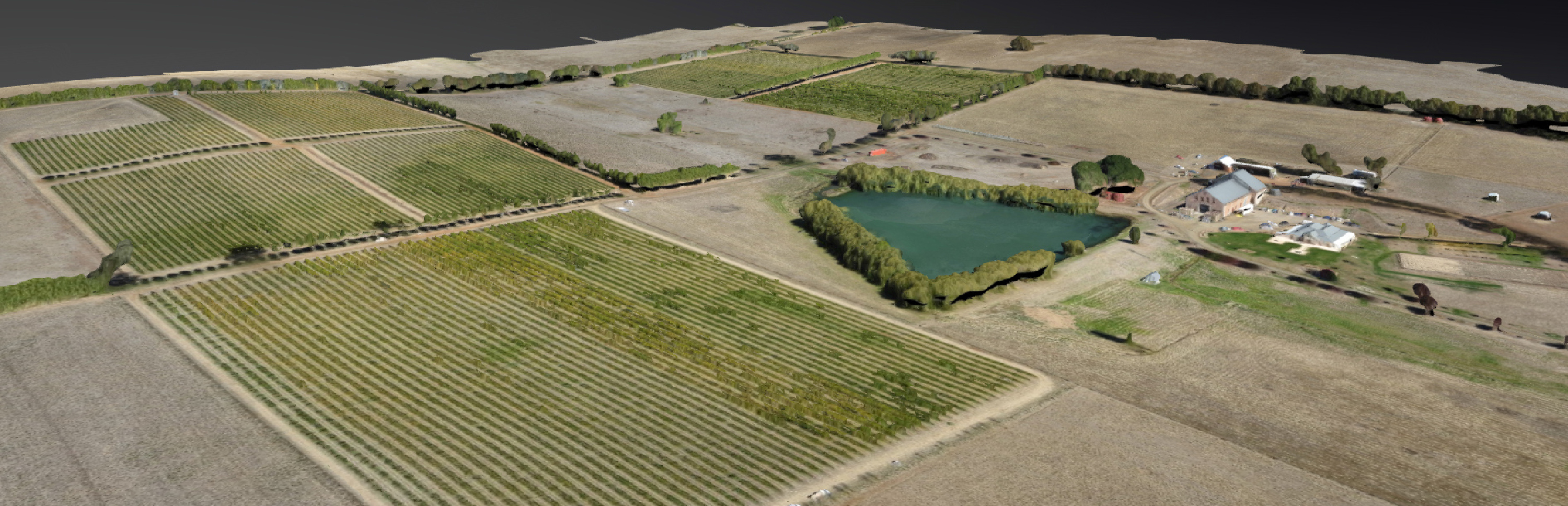

Today they’re watching over the farmyard and vineyard, tomorrow they could be delivering books to your doorstep and coffee to your desk – the possibilities are seemingly endless

Published 24 September 2015

Imagine a world where your coffee flew in every morning direct to your desk.

Where online orders arrived on the doorstep courtesy a robotic deliveryman. Where, instead of digging up your garden from sheer loneliness and boredom, your dog was distracted and entertained with a daily walk guided by a mechanical minder.

Far fetched? Maybe. But thirty years ago the mere idea of an omnipresent, hand-held mobile phone was hard to envisage.

The technology of unmanned aerial vehicles, or what most people refer to as ‘drones’, has advanced exponentially in recent years.

We’re no longer surprised to see a drone buzzing around collecting video footage at an outdoor wedding. Or reading about drones working for the military, being used at crime scenes, delivering emergency aid, sniffing out toxic volcanic gases and checking for post-tsunami radiation leaks.

We’re also starting to get used to video and still images of previously inaccessible sites – the haunting scenes of Chernobyl shot by overhead drone-mounted cameras being a persuasive case in point.

According to Liz Sonenberg, Professor in the Department of Computing and Information Systems Pro Vice-Chancellor (Research Collaboration) and intelligent agent technologies expert at the University of Melbourne, more sophisticated robotic technologies that don’t require direct operator control are gradually becoming understood and opening up the option of regulated use in commercial settings.

“Advances in areas such as visual monitoring of agricultural areas, and inspections of bridges and telecommunications towers, have brought the prices of drones down to such an extent that simpler versions have become, in effect, a mere commodity,” says Professor Sonenberg.

Politics & Society

Keeping up with the droneses: How criminal laws deal with new technology

Unregulated recreational use, when carried out responsibly, will be a boon in some areas.

“Small scale aerial photography, for example, not so long ago inaccessible or expensive to most people, has brought remotely operator-guided drones within easy reach, within visible range.”

Researchers across the University of Melbourne are working in a range of disciplines and on a range of applications relating to drone technology, including in the area of environmental, agricultural and fire management.

Melbourne engineers are harnessing drone capability to collect visual and thermal data to save water, monitor crops and monitor livestock.

Dr Dongryeol Ryu, who leads the Hydrology and Remote Sensing Group and the UAV Unit of Centre for Disaster Management and Public Safety in the Melbourne School of Engineering, has been working with drones for some time.

“The word drones is really a military nickname,” says Dr Ryu. “Our engineering group calls them UAVs, which stands for unmanned aerial vehicles.

“Technological evolution has been driven by the development of mobile phone technology and the miniaturisation of sensing technology like GPS, temperature, and face recognition.”

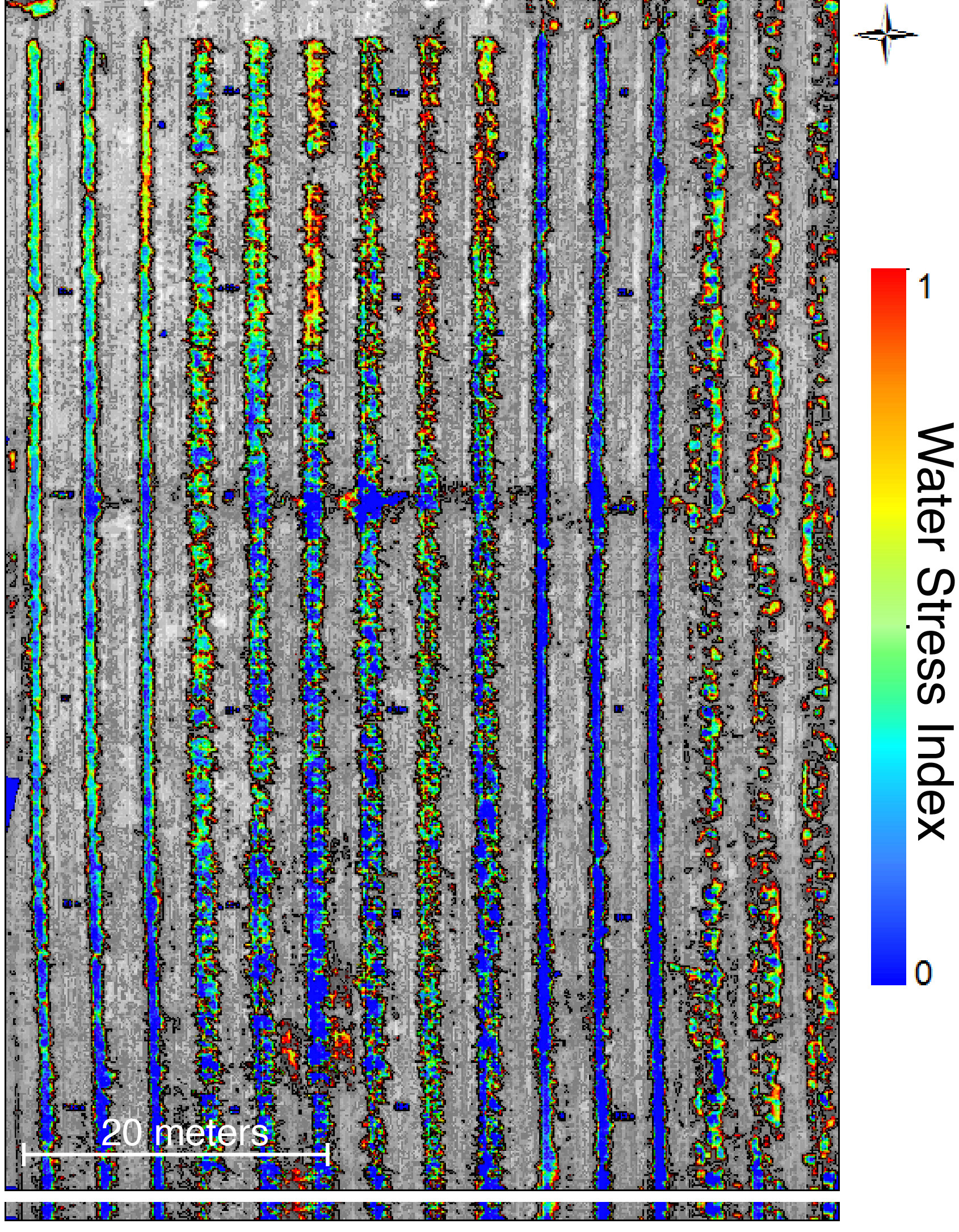

Dr Ryu goes on to explain that drone sensor technologies are the key to their usefulness and that his team uses drones to ‘see’ into the infrared range and check the temperature of crops.

The research carried out by Dr Ryu and his team involves sending out UAVs to fly over landmasses – they have special aviation permissions – to take thermal images. They then process large amounts of sensing data and make it available to farmers, communities and primary industry groups.

“This type of agricultural management also has future applications in environmental land care,” says Dr Ryu.

The data is used to determine crop temperatures, similar to measuring body temperature. “If it’s high, that’s a sign something is wrong.

“Nutrient and water stress increases the temperature of the crop, as do some plant diseases.”

The use of drones means crop stress can be detected before humans are able to do so, and irrigation and water management have become an exact science.

“We call it precision agriculture,” says Dr Ryu.

Unmanned aerial vehicles have also been used in bushfire management to monitor a fire’s spread and identify areas at risk by mapping changes in biomass and detecting potentially hazardous fuel loads.

“UAVs are able to provide high-resolution imagery and collect thermal data accurate to a few centimetres when needed,” says Dr Ryu.

“Combining that data with other satellite data makes for a comprehensive picture for crop farmers, fire fighters, and environmental land care organisations.”

Higher incidences of climate anomalies (such as frosts and heat waves) and increasing water demands, are having an impact on the majority of grape-growing regions globally, leading to early harvests and berry shrivel.

Dr Sigfredo Fuentes is a University of Melbourne senior researcher and international co-ordinator of the Vineyard of the Future Initiative. He is using a ‘multicopter’, nicknamed the ‘viticopter’, developed by mechanical engineering students, and powered by an app, to gather vital information for growers.

“The app will help wine growers determine which vines are starting to become stressed before there are damages that could impact yield and quality of berries,” Dr Fuentes explains.

This will empower viticulturists to make informed irrigation scheduling decisions, and manage fertilisers and canopy.

“New techniques like this will reduce problems like berry shrivel, and help control increased alcohol content in wines, which has been predicted to increase 1 per cent every decade in Australia.

“This really is precision viticulture.”

If you haven’t already seen it, spectacular footage is available on the web of a wedge-tailed eagle deliberately taking out a drone in mid flight. The slow motion version shows the eagle lunging at the drone, using its feet to knock it out of the air.

Some farmers are using drones to round up sheep and cows and one Australian farmer is using drones to successfully monitor lambing ewes.

“Ewes on the point of lambing aren’t bothered by UAVs,” says Matthew Ipsen who runs a farming operation in sheep and crops and owns a business in sheep artificial insemination and pregnancy ultrasound scanning called Ewe Wish, in Wareek, central Victoria.

Mr Ipsen is a 2013 Nuffield scholar and member of the Dookie Farm Committee, which advises the University of Melbourne’s rural campus at Dookie.

“Lamb survival is increased when sheep are in good condition, run in small mobs in multiple bearing ewes, and are left undisturbed for at least six hours,” says Mr Ipsen, “allowing for them to form a maternal bond with their lambs.”

UAVs allow me to check on lambing ewes from the side of the paddock and avoid interrupting other ewes that have lambed and are still in that critical bonding period.

“It’s been a real success.”

The many differences between ground and air vehicles is obvious but with regard to societal acceptance and forms of regulation, Professor Sonenberg points out that there is much to be learned from recent research and development into driverless cars.

“The growing acceptance of what’s possible with cars will surely shape attitudes to deployment of drones,” says Professor Sonenberg, “at least in community and commercial settings and, by osmosis, to deployment in more warlike scenarios.”

Currently, Professor Sonenberg and her team are undertaking research designed to enable drones to move from the current capability of limited autonomy – which she says is generally not much more than limited navigation between pre-defined waypoints – to being able to use on-board sensing to assess and adapt to situations as they emerge during a flight.

“The human designer will inevitably be setting boundaries and constraints to autonomous operation,” says Professor Sonenberg.

Over time, the reasoning capabilities of machines will allow sophisticated adaption to circumstances that don’t depend on constant human intervention.

“As well, we are working on ways for humans to interact with such machines in order for them to be able to intermittently access machine status – when it’s safe to do so – and provide high level guidance to operations when the human has knowledge of the situation that is unavailable to the machine.”

Banner: Drone vs Co/Lima Pix, Flickr