Arts & Culture

The life stories of Gippsland lakes fishers

COVID-19 exposes some of Western culture’s deepest prejudices around death and human remains, ingrained by hundreds of years of past mass death events

Published 21 April 2021

Last April, as New York City’s COVID-19 death toll soared, a photographer captured images of dozens of pine coffins being lowered into trenches. The picture underscored the grim reality of a virus that was killing hundreds a day.

But the pictures – soon followed by others of mass graves in Iran and Brazil – also spoke to an even deeper fear – the loss of individuality in death.

In Western cultures the funeral industry does everything it can to ensure individuality in death: they maintain graves, keep meticulous records, and invest in technologies to protect their sites from floods and forest fires.

Crematoria, in particular, have stringent processes in place to ensure that the identity of the deceased is maintained and that ashes don’t get caught and left in machinery (though of course some does).

Arts & Culture

The life stories of Gippsland lakes fishers

In this sense, the pandemic exposes some of our deepest fears – dying alone and being buried together. But where does this fear of communal burial come from and can it change?

Images of New York’s mass graves were captured by a drone hovering over Hart Island, a mile-long speck of land off the Bronx that has been used as a sanatorium and potter’s field for over 150 years.

Hart Island has been the final resting place for most of the city’s unclaimed dead, including the very poor and the incarcerated. Trench burial there is nothing new. At the height of the AIDS crisis, more than 1200 bodies were buried there each year in pine boxes, 150 to a trench, the dead only identified by a number.

In recent years, the NYC City Council has recognised the island as one of the largest cemeteries in the world for victims of AIDS and put forward a plan to turn it into a park with a special ferry and a new memorial.

Historically, Hart Island (and other paupers’ gravesites across the world) were the solution for the interment of people so marginal they could not pay for – or weren’t recognised as deserving of – a proper burial.

In the early years of AIDS, when the post-mortem contagion risk of the virus was unknown, many funeral directors demanded sealed coffins or refused to handle bodies outright. The stigma around the disease often meant that patients, many of them gay men ostracised by their families, died, and were buried, utterly alone.

Arts & Culture

Bringing new life to cemeteries

Whether someone has an individual grave, has through the ages been a good indication of who in a society is seen as fully human. For a long time, this excluded the destitute, marginalised groups, and the very young – for example in many Christian traditions, children who died before baptism weren’t buried in the main burial ground.

Theorist Judith Butler calls this “grievabilty” – some lives are recognised as worthy of memorialisation while others are deemed less than human and are buried collectively and anonymously.

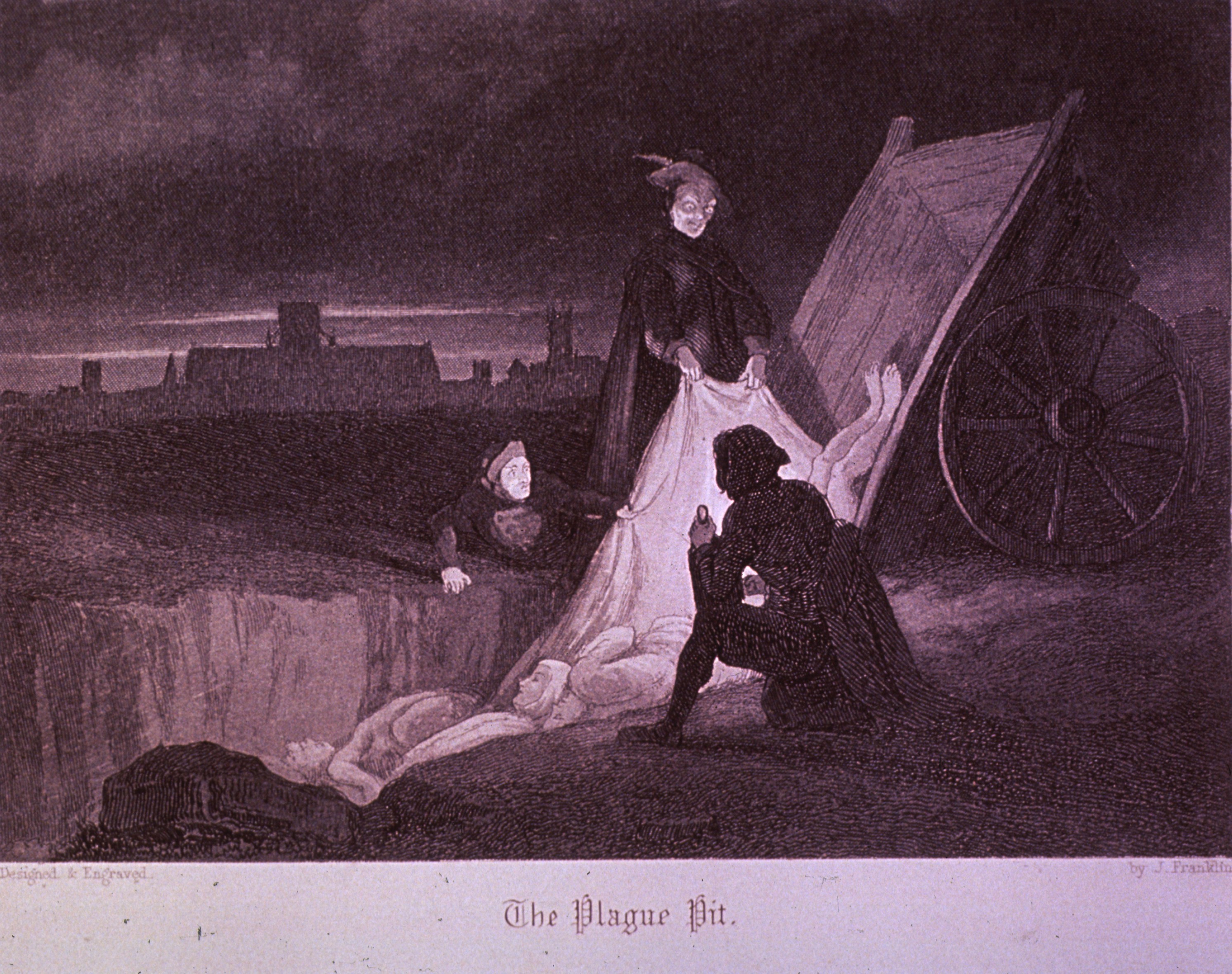

Western fears of the “common grave” go back to the plague pits of Europe and other mass death events. The multiple waves of bubonic plague that swept over European cities for hundreds of years from the middle ages on, underscored the shaky state of medical knowledge and the tenuousness of social bonds.

Writer Daniel Defoe (1660-1731) described London’s 1665 plague as a great equaliser. Carts dumped men, women, and children – naked but for their nightshirts – into hastily-dug holes. Here, rich and poor went in together ‘to be huddled together into the common Grave of Mankind.’

However, our more recent experiences of mass death show that it is precisely the poor (as well as religious and ethnic minorities) who are likely to die, while the well-to-do tend to both evade death and, when they do succumb, they are celebrated with a far greater level of memorialisation.

Death isn’t so much the ‘great leveller’ after all.

Arts & Culture

Journal of the plague year

Images of mass death are shocking and upsetting in a way different to single deaths, perhaps because they are necessarily political in a way that a single death isn’t. For example, the photographer who shot images of Hart Island had his drone seized by police.

Images of mass death can threaten governments and it is one of the reasons why the bodies of fallen soldiers are so rarely seen.

As researchers in death studies who have closely examined the funeral industry, we have heard first-hand accounts from funeral directors and cemetery managers in Australia about the plans that were being made for the very worst at the height of COVID-19 pandemic.

In April, government officials asked cemetery custodians in South Australia to prepare plans for a “mass casualty” event and in Melbourne, there were plans to transform the Convention Centre into a hospital and morgue.

These plans are shocking to people partly because they challenge our Western preoccupation with the individualisation of human remains. However, communal burial need not necessarily be neglectful or dehumanising.

In Japan, communal burial societies are increasingly common. By joining-up, individuals help to offset the costs of grave sites and distribute the ongoing caretaking that would otherwise fall onto their family alone.

Politics & Society

Want to live forever? Here’s how

In a rapidly ageing country, burial societies (called hakatomo – a word compounding ‘grave’ and ‘friend’) are a new form of civil society, with monthly meetings and activities. The cremated ashes of members are interred in mounds, underground vaults, or even in statues of the Buddha – undifferentiated and unlabelled.

In hakatomo societies, this isn’t viewed as dehumanising. Rather, individuality in death is seen as a failure of sociability in life.

The Seattle-based start-up Recompose tried to persuade Americans to re-examine their feelings toward individualised death and communal burial. Founded by Katrina Spade, the original iteration – called the Urban Death Project – involved bodies being placed at the top of a single large silo, where they slowly travelled down through layers of organic matter, decomposing and, eventually, yielding a mass of soil.

In this original design, Spade wasn’t only criticising of the environmental cost of conventional burial practice, but also American culture’s “obsession with individualism” when it comes to the integrity of remains.

In response, Catholic leaders across the U.S. vociferously objected saying the process denied “the uniqueness of the human person.” This is in keeping with the Church’s position on cremation, which is tolerated so long as the individual is maintained in toto – ash-scattering is explicitly forbidden.

And it appears that Spade’s initial plans for communal decomposition appear to have been too much for many clients. In 2017, Recompose shifted the design of their system to seal each person’s remains in an individual vault for treatment, ensuring that families receive soil that can be traced back directly to their loved one.

Arts & Culture

The stuff of death and the death of stuff

Yet, for all of our efforts at memorialising a loved one’s remains, at the end of the day, time will erode all but a few, select graves – most will stand forgotten until bulldozed to make way for more graves. Even in jurisdictions where graves are owned “in perpetuity”, cemeteries can be converted to other uses.

It may be that massed burial will only become more acceptable in Western societies as we adopt new ways of memorialising our loved ones. Already the “life” of someone can increasingly be captured and preserved electronically.

It means that perhaps in a real tangible sense we can have our loved ones with us forever, regardless of the circumstances of their death or where their actual remains may be – and regardless of any societal judgements on who is worth remembering and who isn’t.

Banner: Coffins being buried in a trench on Hart Island, New York, on April 9, 2020. Hart Island’s potter’s field experienced an influx of burials at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Andrew Theodorakis/Getty Images